News - Auld Reekie Retold

-

2min Article

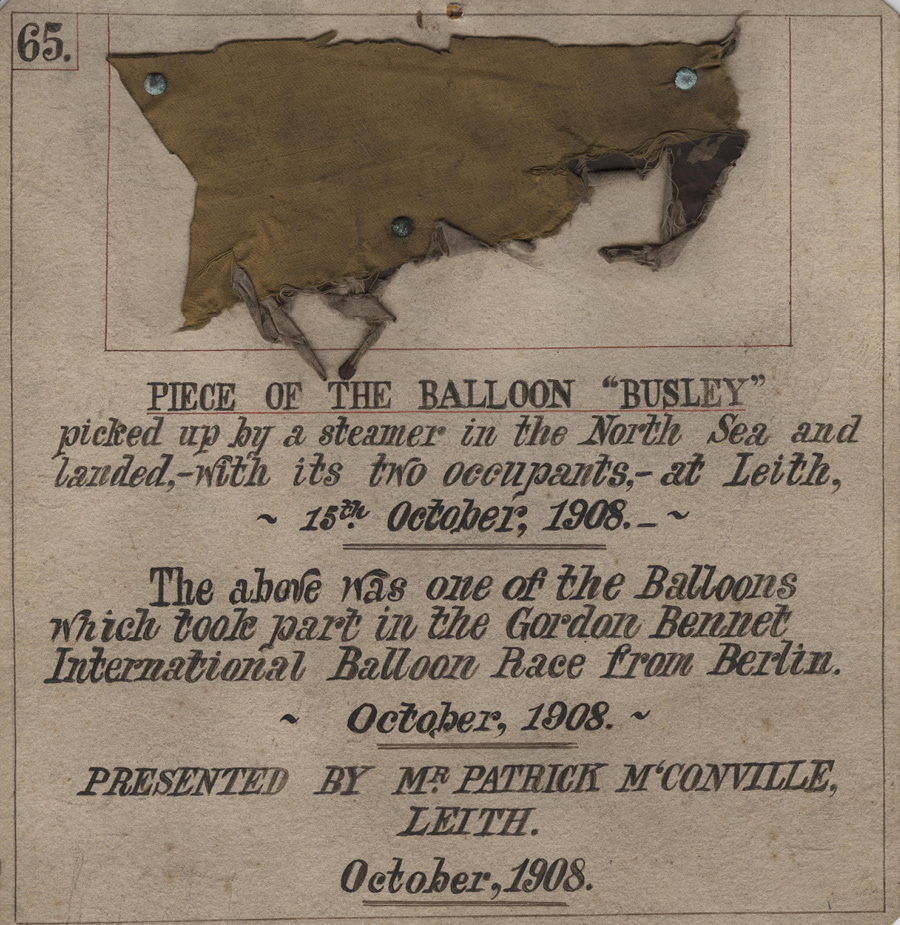

On a cold Autumn day in 1908, high above the grey blanket of the North Sea, a pair of daring German adventurers were in trouble. But what links their air-based escapades to famed New York media mogul James Gordon Bennett and the port of Leith?

1908 saw the third iteration of the much-anticipated Gordon Bennett Cup. The hot air balloon race was established by newspaper owner, socialite and adventurer James Gordon Bennett, the son of Scottish emigrant and founder of the New York Herald, James Gordon Bennett Senior. It is widely thought that the expression of incredulity ‘Gordon Bennett!’ came about due to the outlandish exploits of James Gordon Bennett junior, who raced yachts, played polo and sponsored explorers. The Gordon Bennett Balloon Race continues today.

The 1908 Gordon Bennett Cup race began in Berlin, Germany and involved twenty-three hot air balloons piloted by teams from eight countries. The aim of the race was to fly as far away from the launch point as possible without landing along the way. Consequently, contestants ended up in some peculiar locations. The winners of the 1910 race ended up in the wilderness of Quebec, Canada, finally emerging after ten days during which they were presumed dead. Other balloonists have ended up in less exceptional surroundings - one team in the 1908 Berlin race hit a fence soon after ascending and ended up rapidly descending 3000 feet before landing on the roof of a house in a Berlin suburb. Luckily the balloonists and the house’s inhabitants survived.

At five in the morning on 15 October 1908, four days after their embarkation from Berlin, team-mates Dr Niemeyer and Hans Hiedemann found themselves lost. The pair of German balloonists in the balloon ‘Busley’ had passed over the German seaside town of Cuxhaven four hours previously with a wind driving them towards the centre of England. However, something was wrong. The wind changed and instead of heading west they found themselves picking up speed and going further north. The team ascertained they were north-west of Heligoland and somehow managed to communicate with a passing coal steamer that was heading to Edinburgh. Niemeyer and Hiedemann vented their balloon to bring them close to the ship but just as they were alongside, the balloon was picked up again by strong winds and was carried further away.

The balloon eventually crashed into the sea, and the lucky adventurers were picked up by the ship. The balloon was later recovered but its log-book and instruments were lost. Niemeyer and Hiedemann joined the ship’s crew on their journey to Edinburgh and arrived at Leith the same day. At 3.24pm on 15 October, Niemeyer sent a telegram to confirm the team’s location and their removal from the race.

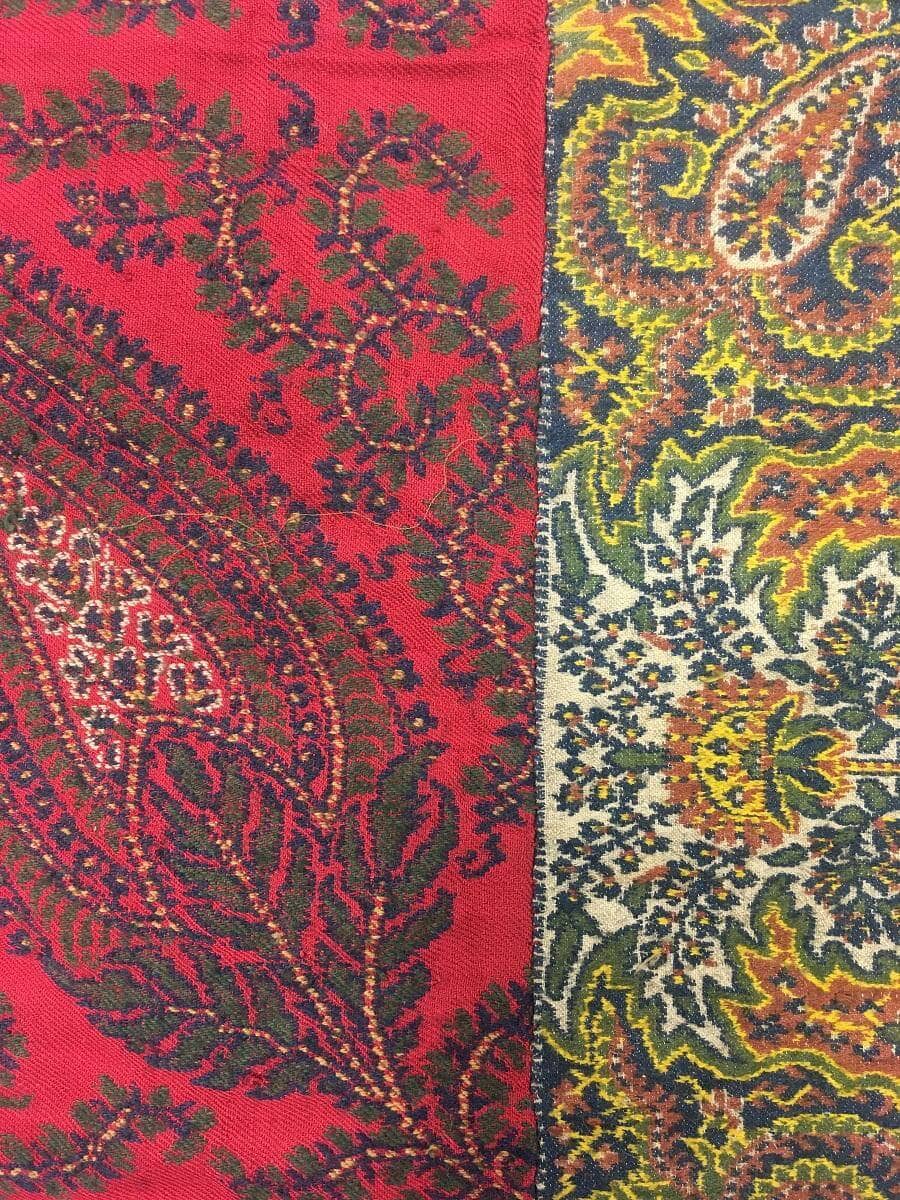

This piece of material formed part of the recovered balloon ‘Busley’ and was presented to Museums & Galleries Edinburgh. It’s tempting to imagine the crew of the Leith-bound coal steamer looking up at the sky above the North Sea and exclaiming ‘Gordon Bennett, that balloon’s coming straight for us!’

-

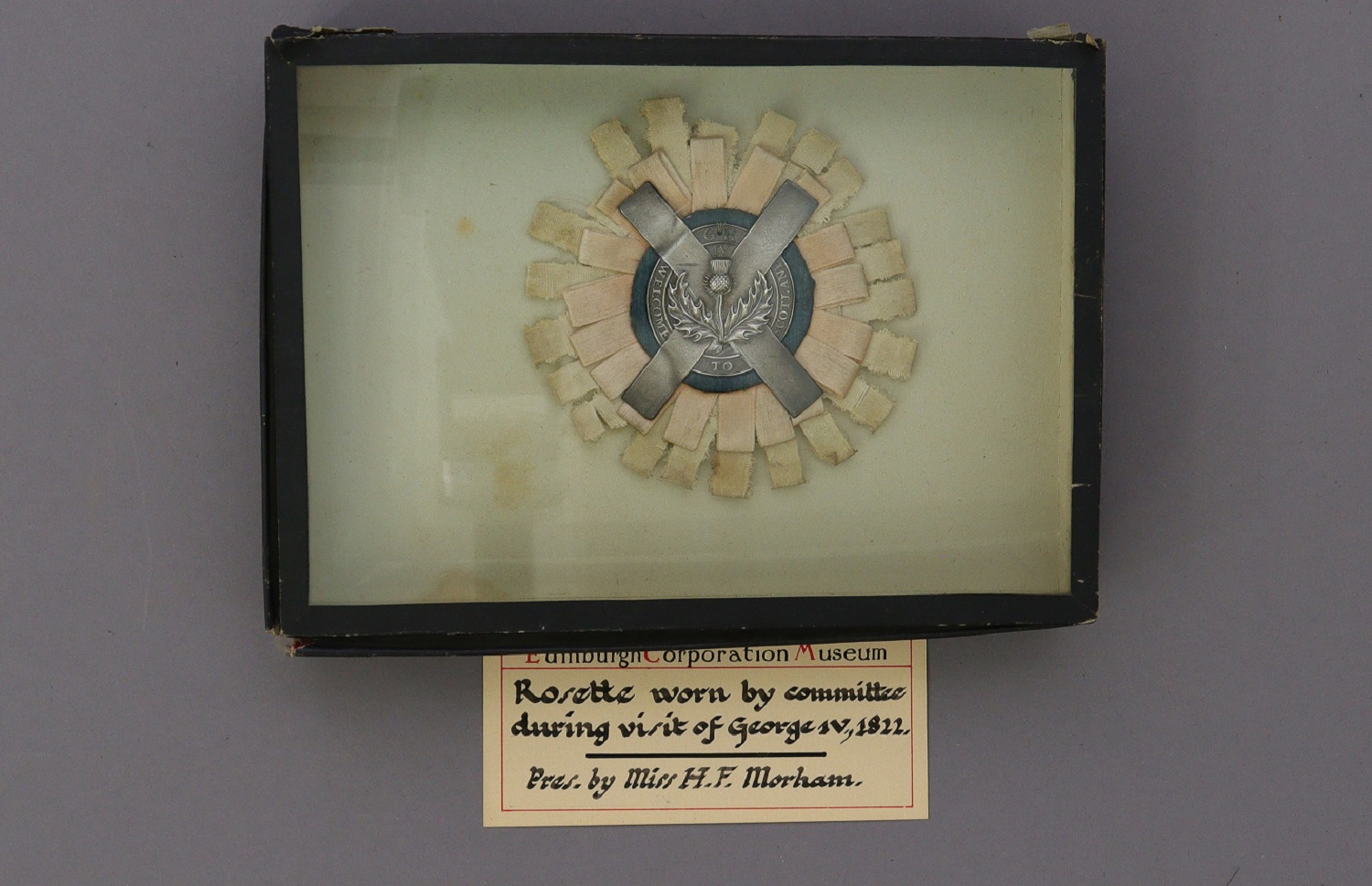

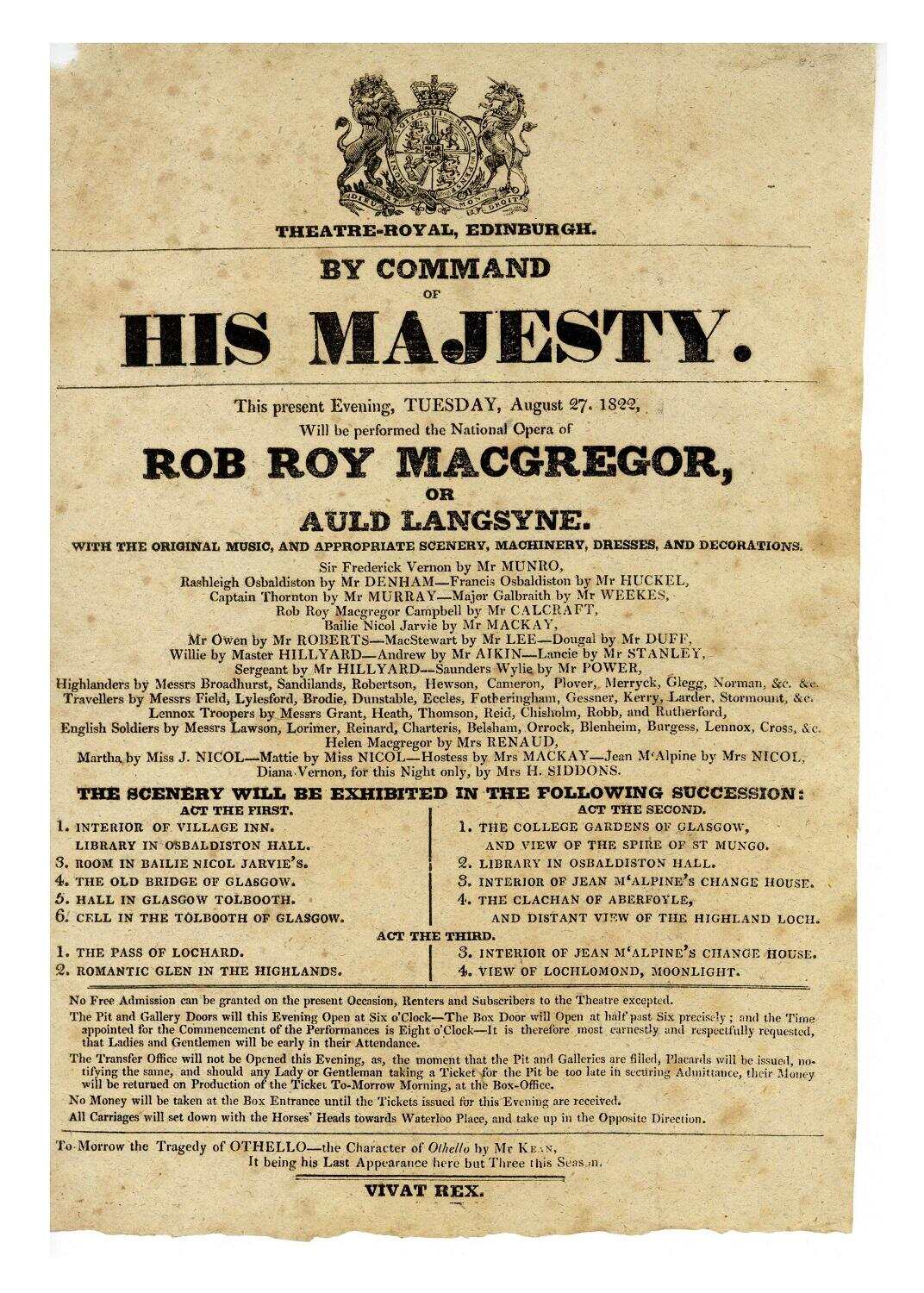

August 2022 marks the 200th anniversary of the Royal Visit of King George IV to Edinburgh. The Royal Visit to Edinburgh was the first by a British monarch since the parliamentary Union of 1707. Orchestrated by Sir Walter Scott, the Visit used public ceremonies, dress, objects and pamphlets to celebrate George IV and show the people of Scotland that he was the legitimate heir to Scotland’s national past. Highland dress was encouraged, the cityscape was altered to look its best, and stands for spectators lined the streets to allow everyone a glimpse of their monarch. Museums & Galleries Edinburgh have a significant collection of objects relating to the Visit, from a fine tartan outfit worn by an official guest down to the rough metal holders used by the city's inhabitants for candles lining the Royal Mile. One item from the visit however has remained hidden for years, unknown by anyone. In this blog, Auld Reekie Retold project manager Nico Tyack looks at how a tiny but unique rosette was forgotten about, and how it was rediscovered.

The various items relating to the Royal Visit are not from one single collection, but have been collected through gifts or purchases over decades. The curators at the Museums and Galleries have a good collective expertise about these items which sit within the wider collection areas of social history, applied and decorative art, and fine art. Many are on display at the Museum of Edinburgh, and to mark the occasion of the anniversary, a painting from the City Art Centre collection showing the arrival of the King at Leith harbour has been put on display here too. The Auld Reekie Retold team had a chance to catch up with the items on display at a recent Collections Live in-gallery event where they were all photographed and checked. The Royal Visit collection is so well recognised that some items were lent to the National Museum of Scotland for their "Wild and Majestic" exhibition in 2018. Some feature in an online exhibition marking the visit on the City of Edinburgh council Libraries' "Our Town Stories" resource. The team felt that this collection was in good order; well documented, digitised and much of it "out there" for people to enjoy. Or so they thought.....

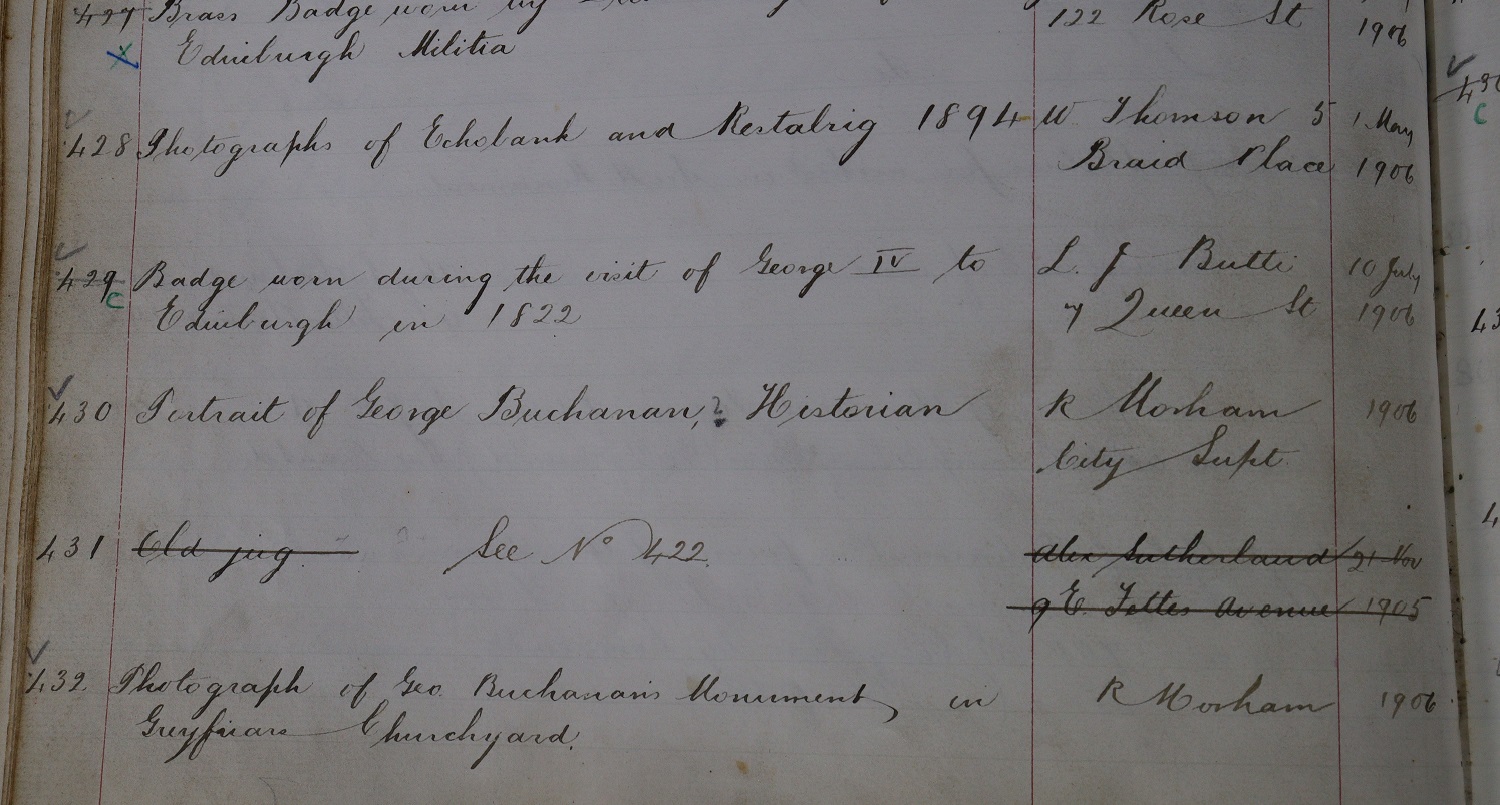

Recently, curator of applied art Helen Edwards was sorting through some old boxes and files at the Museum of Edinburgh as part of the Auld Reekie Retold project. She found two small wooden boxes with glass lids. One box was empty, but the other contained a delicate silk rosette with a silver saltire and thistle and the text “Welcome to Scotland”. Helen saw the link with the royal visit, but some museum detective work was needed to find out more about these items, involving a trawl through decades of documents, inventories, lists, and letters.

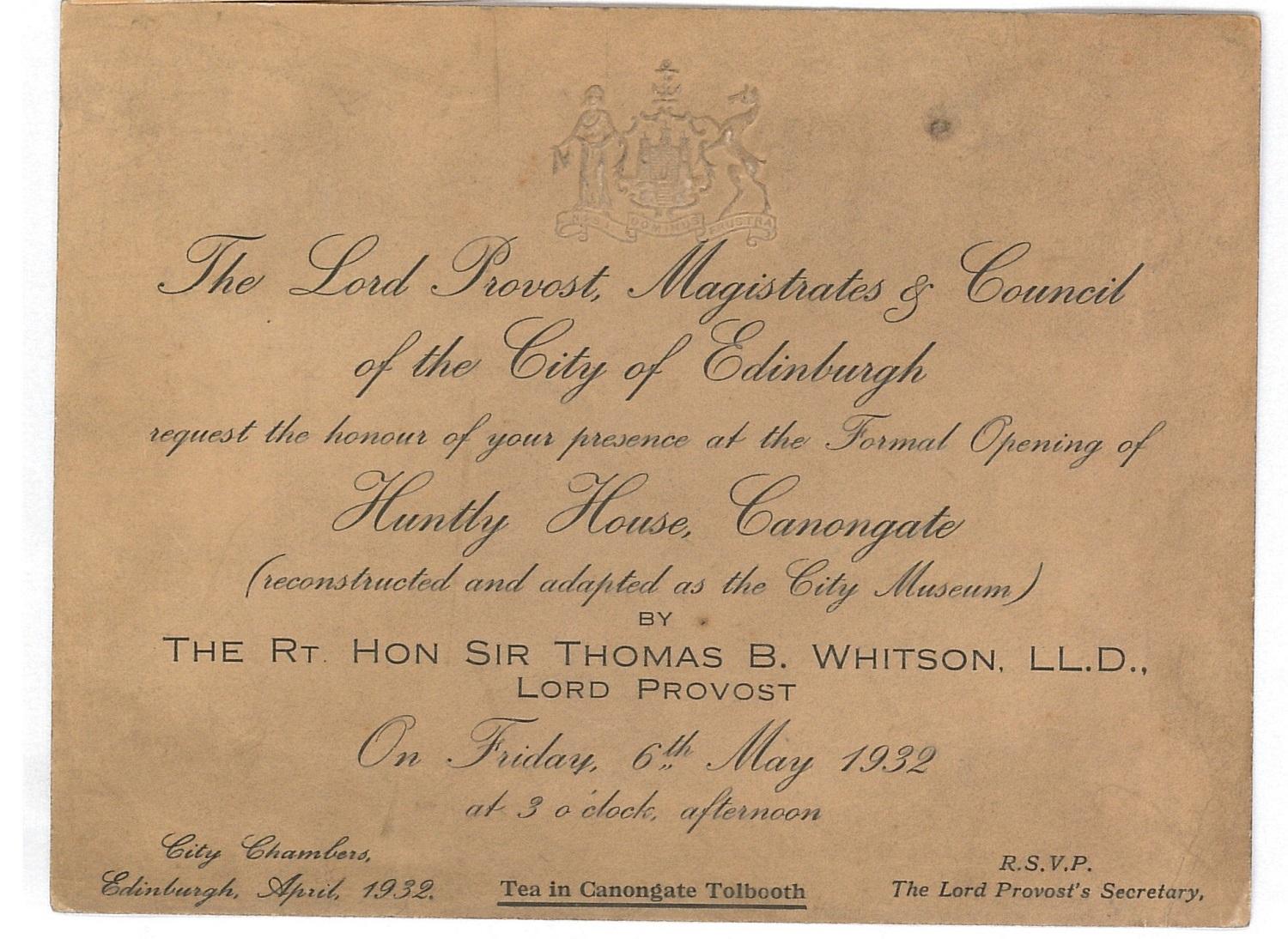

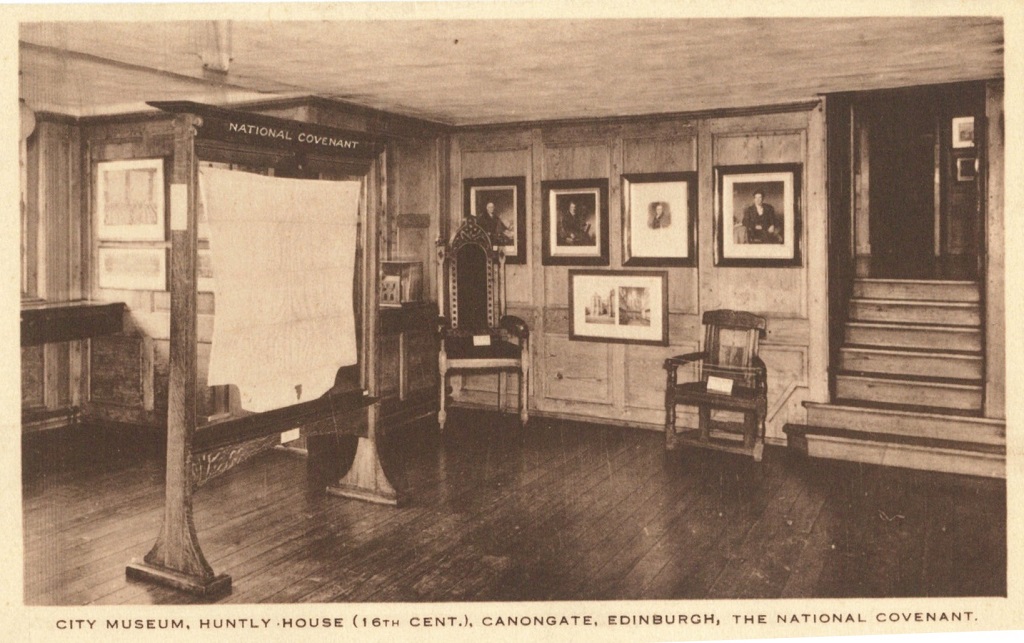

Both boxes contained small paper labels with a handwritten caption and the printed heading "Edinburgh Corporation Museum". This was the Council's very first museum, based at the City Chambers on the High Street, You can read more about this early museum on this Auld Reekie Retold blog. Both labels were for rosettes worn during the Royal Visit; one stated the rosette missing from the box had been donated by a L. J. Butti, and the second rosette in the box was donated by a Miss Moreham.

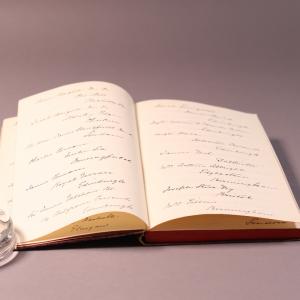

The labels were both written in the same style, and curators knew they dated from some time in the very late 1800s or early 1900s. Most museums keep a running list of all items in their collections called the Accessions Register. These books are the bedrock of any collection. They are as important as the Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages is for people. Anything coming in is listed in these books, with information about how they came to the museum; were they donations or bought? Who from? When? Why? A quick search on the Register and its modern day equivalent, the computerised database quickly allowed curators to match the label from the Butti rosette to a known rosette in the store. The second rosette from Miss Moreham was a little trickier.

A search for the donor's name found nothing, and there were no other objects listed in the register which fitted the description of this distinctive rosette. Curators concluded that the rosette must have gone on display at the Corporation Museum but was never formally listed. Without a record in the Register, the rosette simply couldn't be tracked and became lost and unknown. Have you ever found a wallet in the street? Imagine there are no cards there with the owner's name. What can you do? It is impossible to trace it back to anybody, just as it was impossible for this rosette to be looked after properly.

But now that the rosette has been found again, it has been recorded, entered in the Register and the database with all the information the curators know about it. Crucially, there is now a way to keep track of it as it embarks on its life as a museum item, moving from store to display, maybe even out on loan to another museum. It has been given a new life.

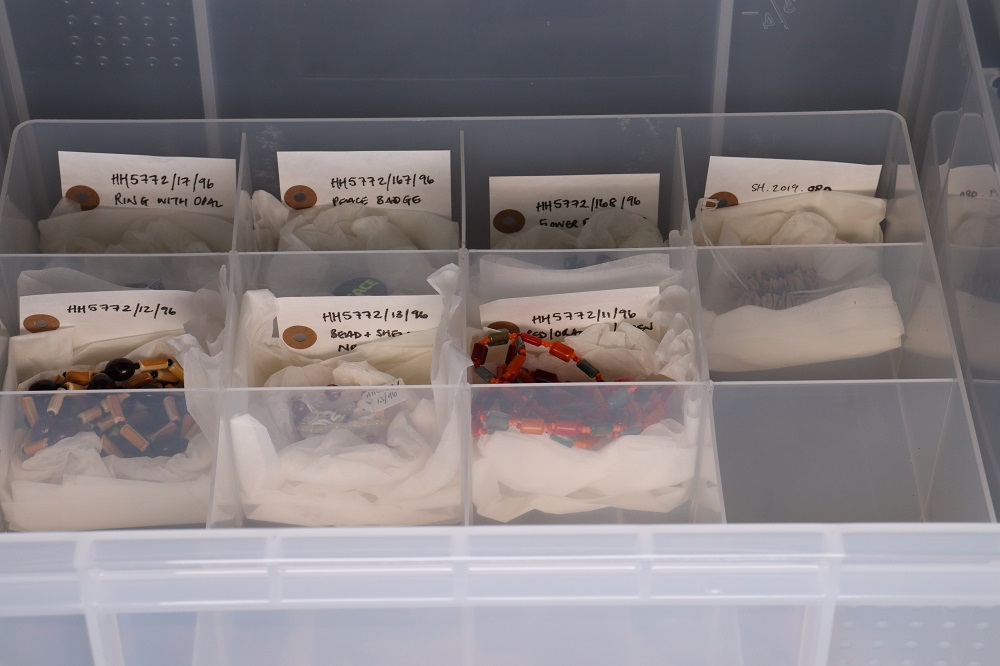

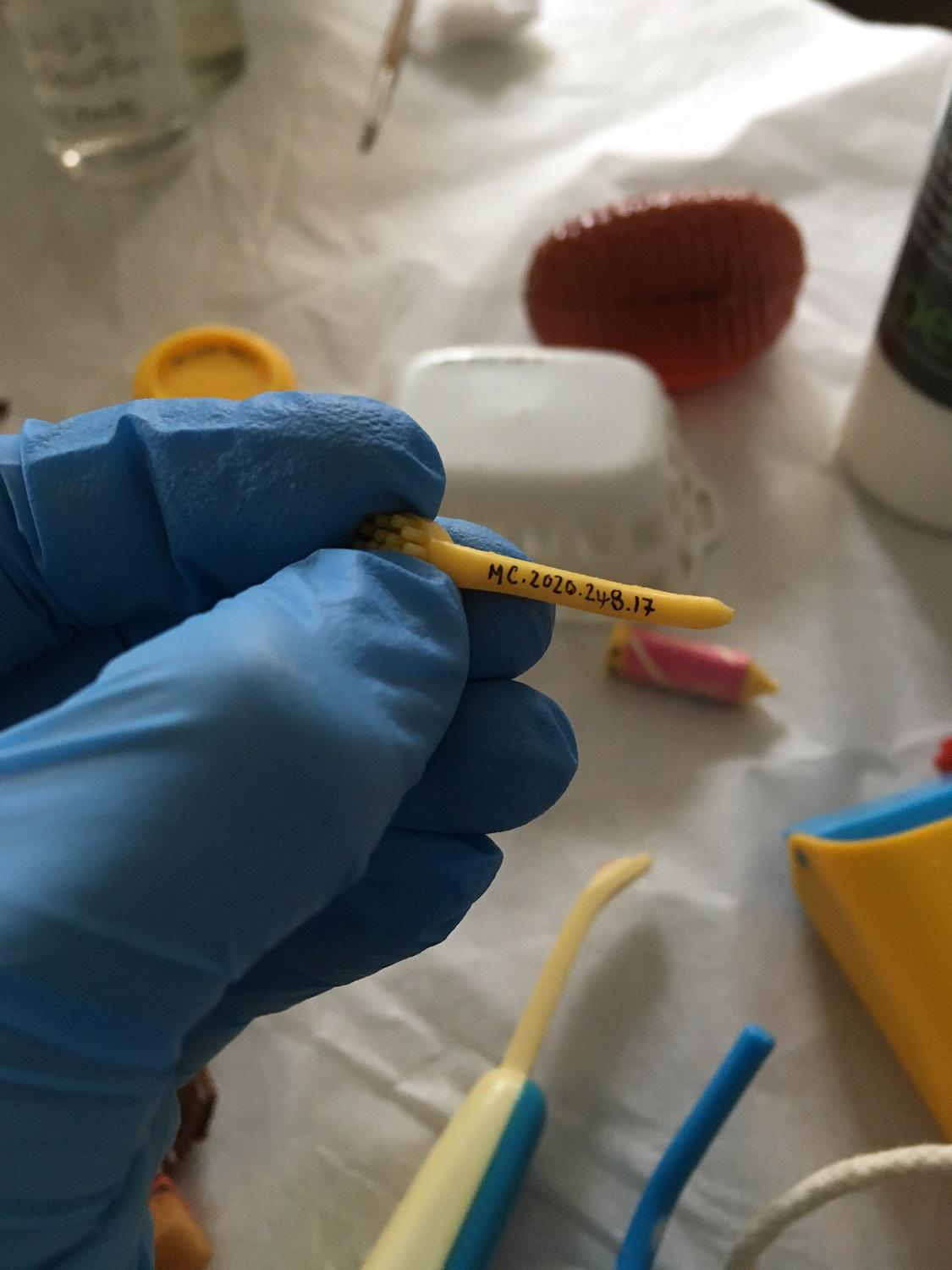

Since 2019, the Auld Reekie Retold project has found thousands of items from the museum’s earliest days with little or no listed information. They weren’t ‘lost’ exactly – in the language we use today, they were ‘location unverified’ – hiding somewhere in storage, awaiting rediscovery. The team has been working tirelessly to uncover these objects and match them back up with their records. Adding the records to our database means these objects won’t be able to hide again! Meanwhile, curators are researching these rediscovered objects to improve the records and start conversations with the people of Edinburgh about what these items can tell us about the city and its history.

-

In June 2021 the Auld Reekie Retold blog explored a mystery box of photographs from a house in Newhaven depicting the Crawford Family. Applied Art Curator Helen Edwards had been researching the pictures during lockdown restrictions using online census records. Her work had uncovered a network of family relationships, but Covid rules prevented her from physically meeting with anyone who might be able to shed light on the photographs.

Collections Engagement Officer Russell Clegg picked up the trail once the blog went live and meeting in person became possible. This led to a flurry of community activity and meetings which brought new information forward. A more detailed picture of the Crawford family began to emerge. In this blog, Russell explains the process that led to the new discoveries, and how they add to our picture of the Crawfords and Newhaven.

In the final part of her blog on the Crawford Family photos, Helen made a tantalising suggestion: ‘Perhaps this blog will spark some memories and we can add to their history?’

How could I resist wanting to follow this up, especially as we were moving towards a time in the Summer and Autumn of 2021 when small scale activities with the public were beginning to resume?

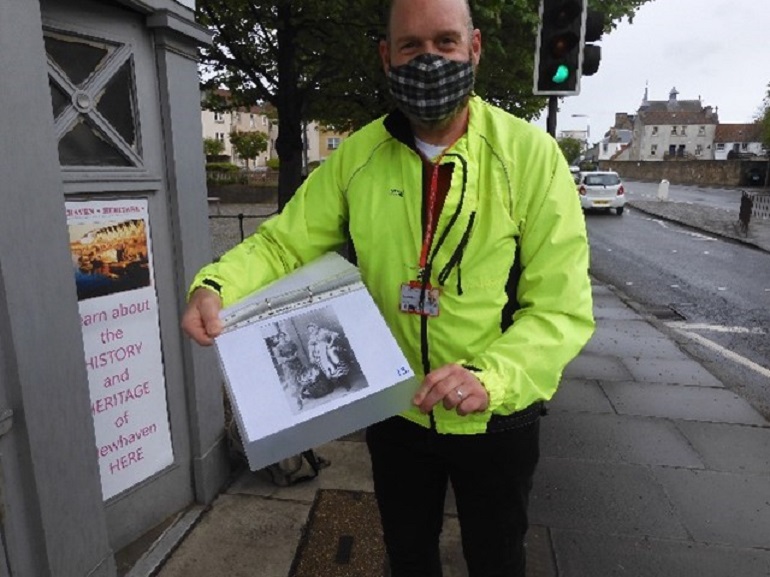

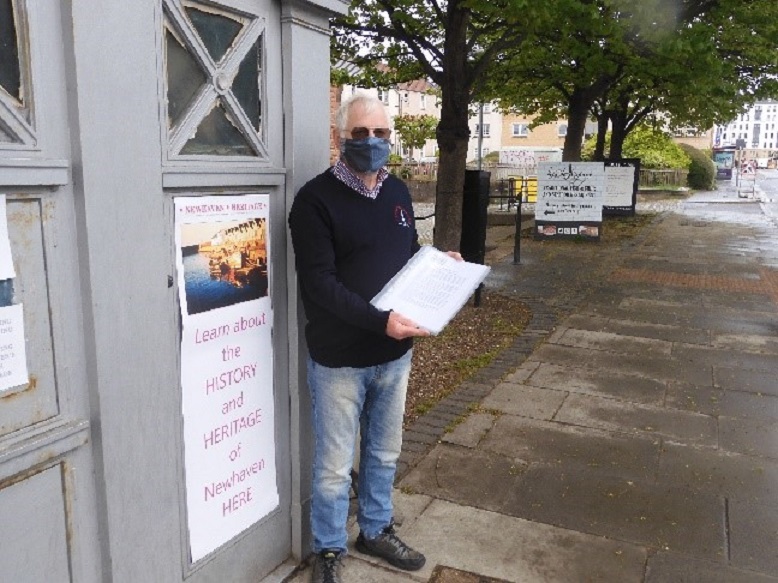

Museums and Galleries Edinburgh have good links with the Newhaven Community, and we had the idea of producing facsimiles of the Crawford photographs which could be deposited with Newhaven Heritage Centre at their ‘drop-in’ Police Box near the harbour.

Dougie Ratcliffe from Newhaven Heritage agreed to meet me there for the handover of two folders of images and to have these available when folk dropped by on his Saturday mornings at the Police Box. Dougie would also be able to circulate the folders to local experts on Newhaven history who lived in the community.

Why do it this way? Although online sessions were popular during the pandemic restrictions, this wasn’t deemed appropriate for our purposes. We wanted folk to be able to see the images close-up and to annotate them if required. Not everyone we were trying to reach out to was necessarily able to engage digitally. To discover more about Grace and her family we had to ‘return’ the photos back to their home community.

In addition to meeting Dougie, I wrote a post on the Bow Tow Facebook page, which serves the Newhaven community and its diaspora, raising awareness of our activity and linking readers to the original blog.

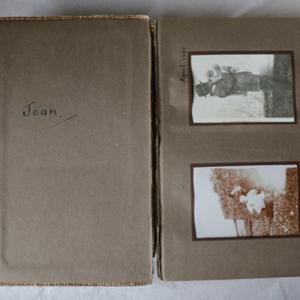

By late summer 2021 we had a breakthrough. Descendants of Jean Crawford, Grace’s younger sister, had seen the Facebook post and met with Dougie at the Police Box to view the scanned photographs. Aileen Watt and her daughter Chel Rennie, respectively the granddaughter and great-granddaughter of Jean, were keen to see the original collection of images and in September they met with me at the Museum Collections Centre for a ‘story-catching’ session around the Crawford photo cache.

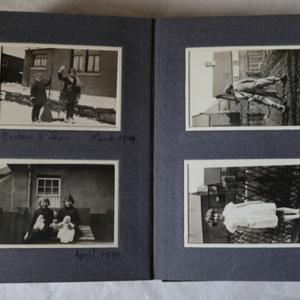

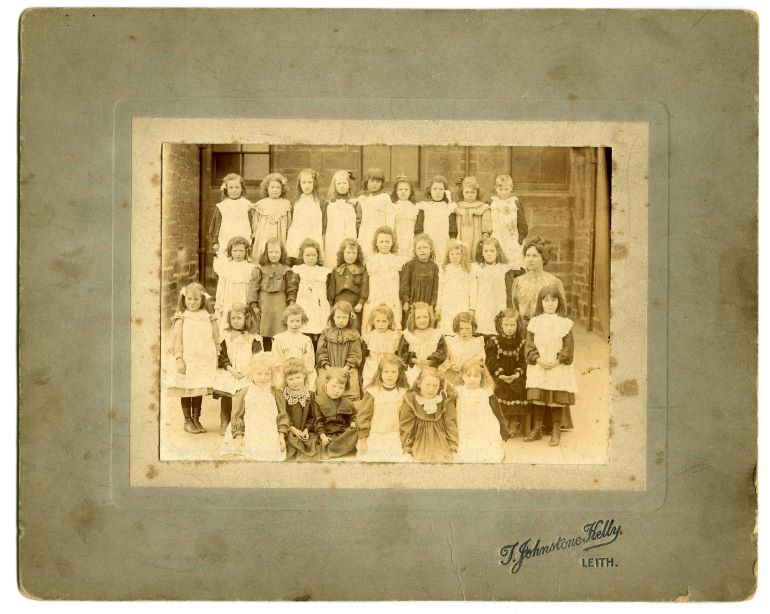

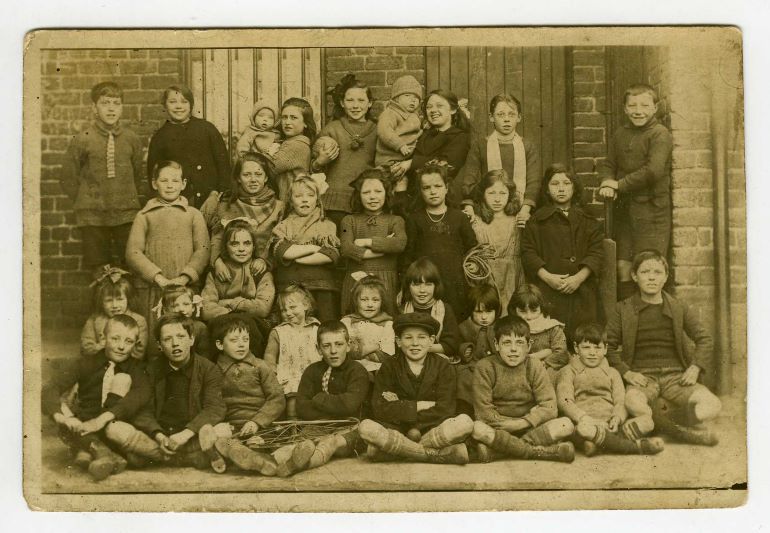

This photograph of the Crawfords shows them minus their final child, Jean, who was born in 1910. Aileen was able to tell me more about John Carnie Crawford, the head of the family, and his Leith-born wife Jane (Jean) Somerville. He was known as ‘Jock’ to friends and family and worked as a coal trimmer, sizing and levelling the coal whilst it was in a ship’s hold – a dangerous job by all accounts. Mother Jean, although not formally employed as such, officiated at births and deaths in the community – helping her neighbours in times of need.

Aileen understands that Jock lived at 16 Parliament Square, a property which had been divided into flats. The Crawford’s flat had been owned by a relative, Robert Carnie, and later in their lives both Grace Crawford and her elder sister Meg (or ‘Meggie’, not ‘Maggie’ as previously thought) occupied a flat each at the same property.

As happened to many Newhaveners, both Meg and Grace were relocated to Granton when the properties were scheduled for demolition in the 1970s. Aileen believes that the property which Meg and Grace occupied still stands and that the cache of photographs must have belonged to Meg Crawford and was left there after she had moved out.

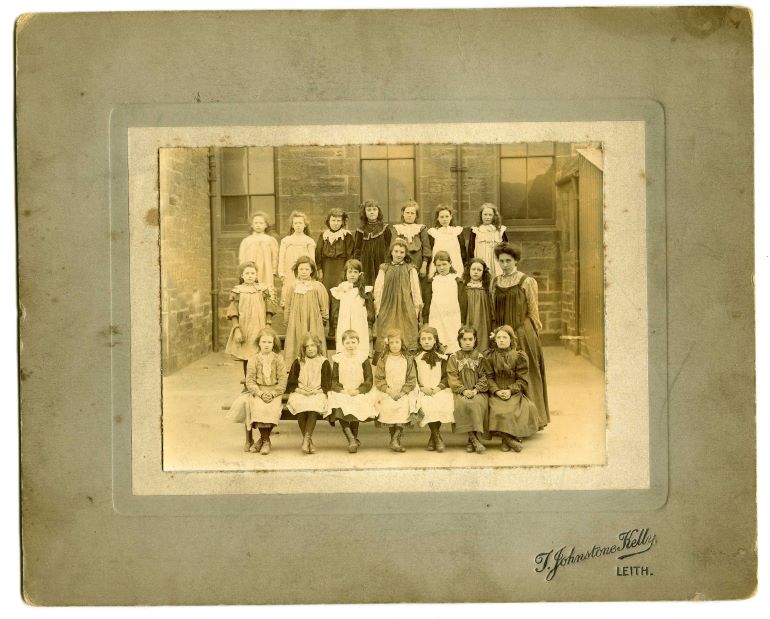

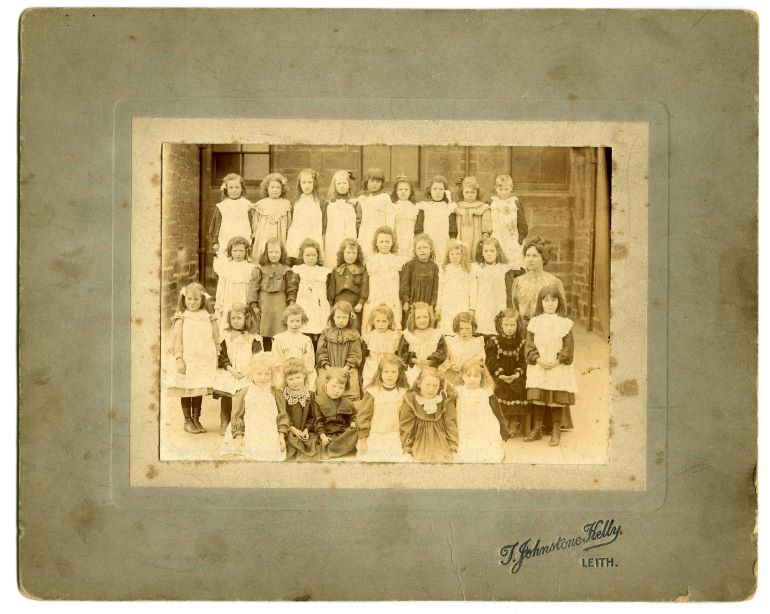

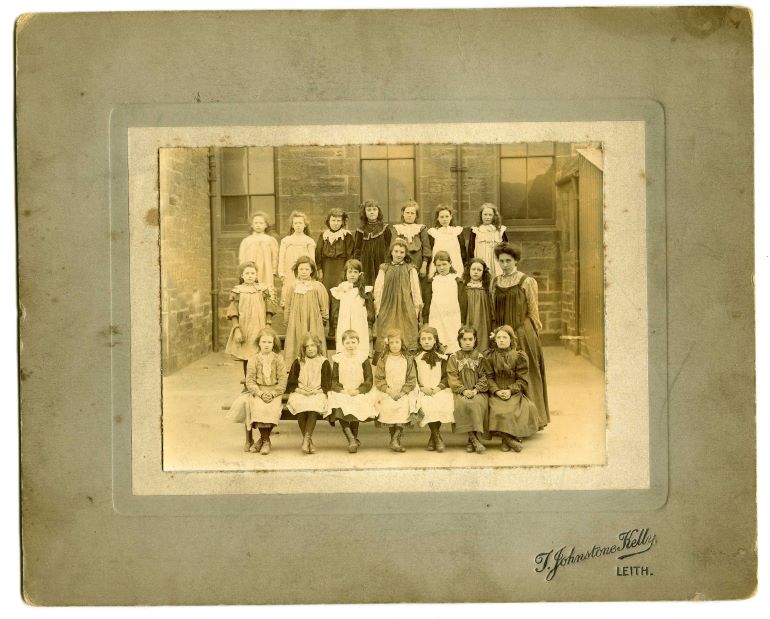

Aileen confirmed that all three Crawford daughters received their elementary education at Victoria Primary School. In the first photo, Grace is pictured in the top row, third from the left. In the second photo, Meg is seen on the top row, third from the right.

Our conversation turned to the Crawford children in later life. The image above shows Meg, on the right, and sister Grace in traditional fishwives’ costume. Meg went on to sing in the Newhaven Fisherwomen’s Choir as an adult. She worked in the Bell’s whisky bond in Leith and as a favourite treat, Aileen recalls ‘Auntie’ Meg taking her to the café in Jenners’ Department Store to eat ‘Snowballs’!

In the first blog, Helen Edwards mentioned the challenges of identifying those pictured in the photographs and how they were related, especially if they had been annotated incorrectly. A mystery regarding the two images below was solved by Aileen and Chel. Helen surmised correctly that the first photo was indeed Jean Crawford, Aileen’s grandmother. The second sitter is not a Crawford at all! According to Aileen, this is Jean’s best friend Peggy Pruce therefore solving the question around the girls’ ages, which would have been similar when the photos were taken.

The ‘story catching’ session was a fascinating exploration into the narratives surrounding the Crawford Family photographs and demonstrated how collections come alive when folk can gather together and share insights and information. We may not have found all the answers posed in the first blog, but the memories shared painted a vivid description of Grace and her siblings, and gave voice to their lives.

-

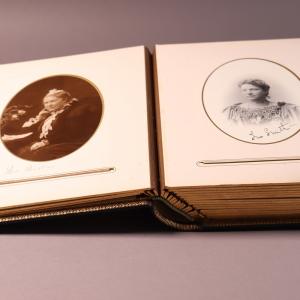

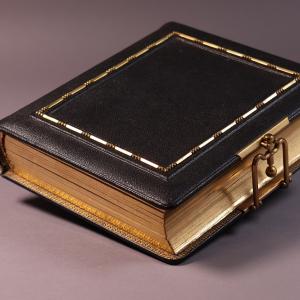

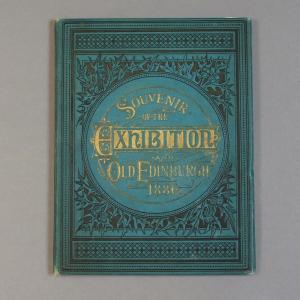

Welcome to the Auld Reekie Retold Podcast from Museums & Galleries Edinburgh. This is our ninth episode and today you’ll hear from Suzy Murray and Victoria Garrington who will be discussing the curious story behind a fascinating cabinet card photographic viewer in the collections. We'll start off from the owner, Eliza Wigham, and take a journey through temperance, womens rights and the 1886 Edinburgh Exhibition! We have been creating the podcast from home, so please excuse any inconsistencies in the audio.

To see the more of the photographic collections head to Capital Collections.

You can get the podcast on most major podcast providers so look for Auld Reekie Retold to subscribe on your preferred platform. Join the conversation at @EdinCulture on Twitter, @museumsgalleriesedinburgh on Instagram and Museums & Galleries Edinburgh on Facebook. Tag us using #AuldReekieRetold

-

Welcome to the Auld Reekie Retold Podcast from Museums & Galleries Edinburgh. This is our eighth episode and today you’ll hear from Gwen Thomas and Helen Scott who will be discussing photography in our Fine Art collections and the photographic process, as well as looking at photographic preservation. We have been creating the podcast from home, so please excuse any inconsistencies in the audio.

To see the more of the photographic collections head to Capital Collections.

You can get the podcast on most major podcast providers so look for Auld Reekie Retold to subscribe on your preferred platform.

Join the conversation at @EdinCulture on Twitter, @museumsgalleriesedinburgh on Instagram and Museums & Galleries Edinburgh on Facebook. Tag us using #AuldReekieRetold

-

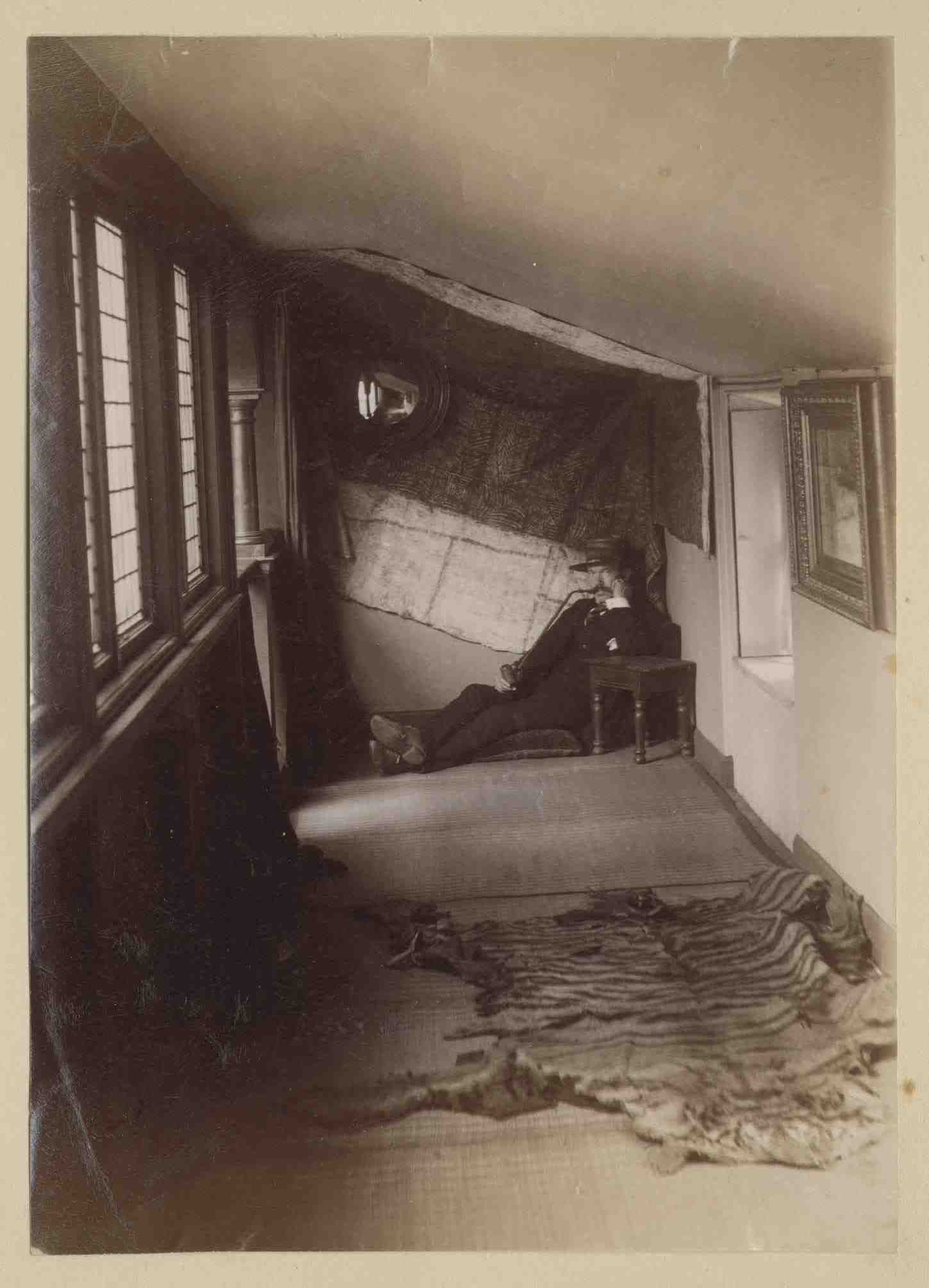

Welcome to the Auld Reekie Retold Podcast from Museums & Galleries Edinburgh. This is our seventh episode and today you’ll hear from Oliver Taylor and Susan Gardner. We are looking at some very early domestic photography and discussing how photography brings us closer to our loved ones. We have been creating the podcast from home, so please excuse any inconsistencies in the audio.

To see the photographic albums head to Capital Collections.

You can get the podcast on most major podcast providers so look for Auld Reekie Retold to subscribe on your preferred platform.

Join the conversation at @EdinCulture on Twitter, @museumsgalleriesedinburgh on Instagram and Museums & Galleries Edinburgh on Facebook. Tag us using #AuldReekieRetold

-

In this Auld Reekie Retold blog, Gemma Henderson, history curator, explores the story of the Edinburgh Bridewell.

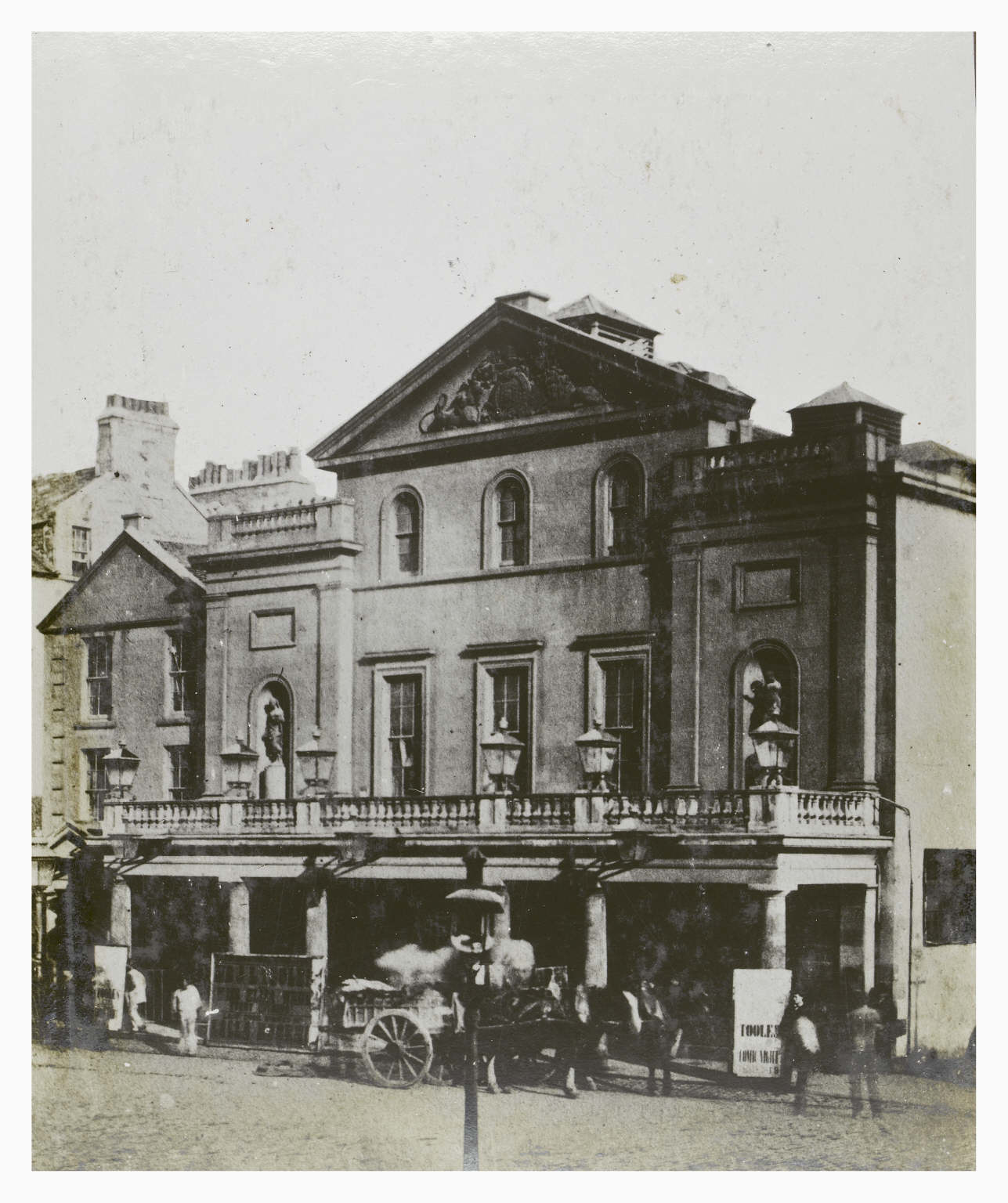

Calton Hill is well known as the site of the former Calton Jail, opened in 1817 and at one time the largest prison in Scotland. However, the lesser known Edinburgh Bridewell, or jail for petty offenders, had stood on this site for almost thirty years before Calton Jail opened its doors.

By the mid-18th century, capital and corporal penalties were gradually giving way to incarceration as a preferred form of punishment. In Edinburgh at this time, building of the New Town was well underway and town officials wanted to project an image of Edinburgh as a modern and enlightened city, but it was becoming clear that existing prison facilities were hugely inadequate and undermining of this effort.

The main prison was the Tolbooth located on the High Street at the North West corner of St Giles Cathedral. An ancient, run-down building known for its insanitary, overcrowded conditions and a general embarrassment to the town.

As the number of offenders serving prison sentences increased, so too did pressure on the existing prisons. An influx of those being convicted of political ‘crimes’ in the wake of the outbreak of the French Revolution exacerbated the problem and it was feared that in the close confines of an overcrowded prison, these prisoners could spread their ‘dangerous’ ideas of liberty, equality and fraternity to other criminals.

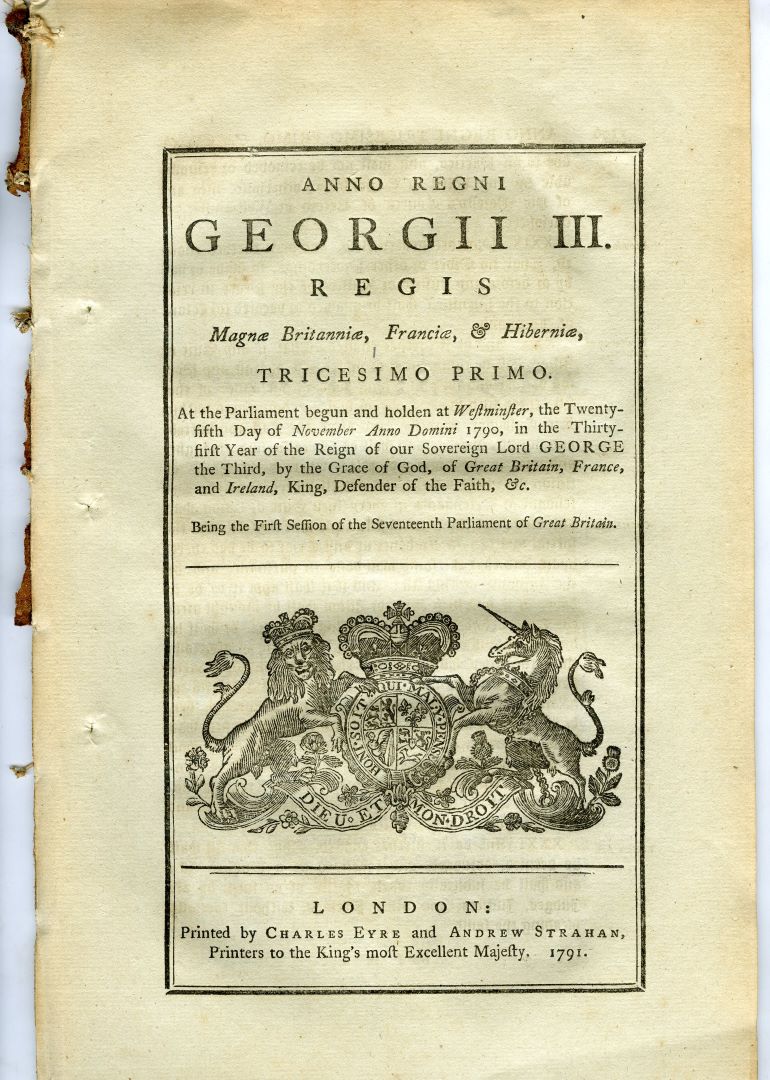

Faced with these fears and bolstered by pressure from the growing Prison Reform Movement, a solution was sought. Throughout the 1780s early attempts were made to design a new facility and plans were presented by several different architects including James Craig, architect of the City’s New Town, in 1780, and James Brown, designer of George Square, in 1782. However, it was not until 1790 that a petition was made to the House of Commons to bring in a bill for erecting a new bridewell and gaol. This was approved on the 25th of November 1790 and laid out the terms of the type of building and the way in which it would be run and maintained. We have this document within our Museums & Galleries Edinburgh collection.

The prolific Scottish architect Robert Adam was appointed as the designer of the new gaol and bridewell. He presented several elaborate plans for the site including a design to build a bridge linking the Old and New Towns of the City but eventually a less ambitious plan was accepted, and a site was selected on Calton Hill for its construction.

No doubt economic factors played a significant part in the selection of his pared down design and although the 1790 Act of Parliament set out plans to build a Bridewell, a house of correction and a prison, only the Bridewell was constructed.

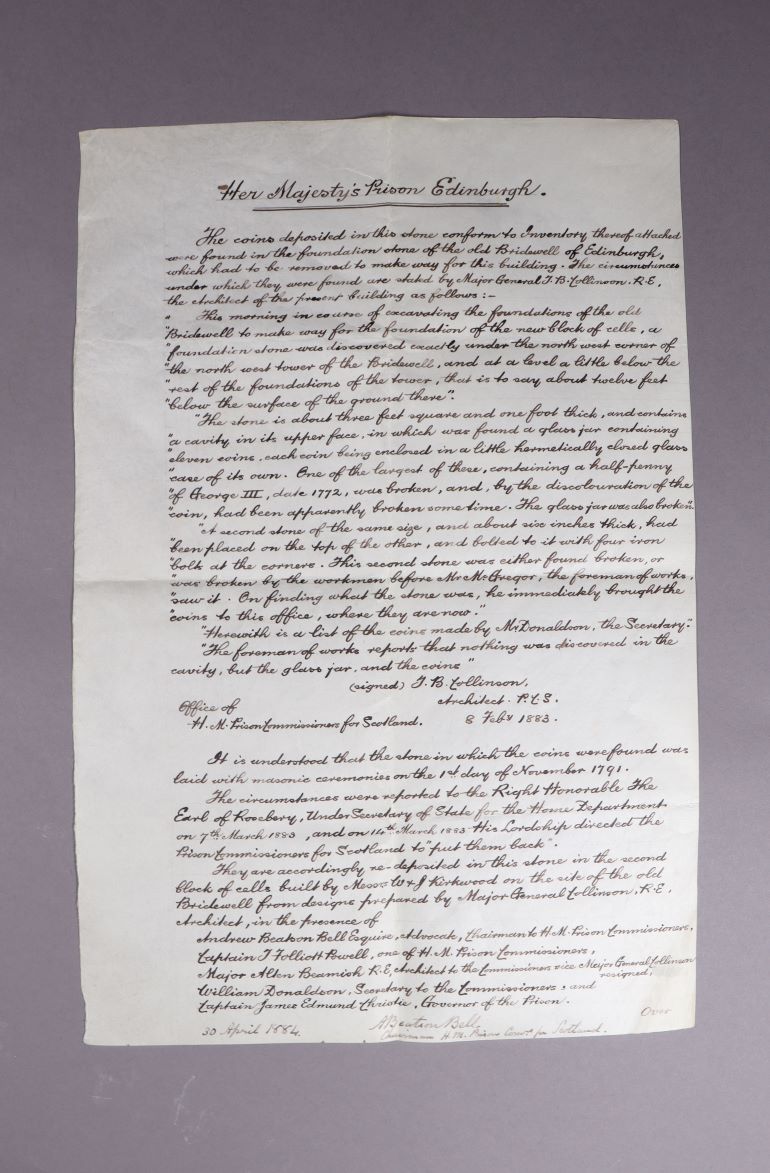

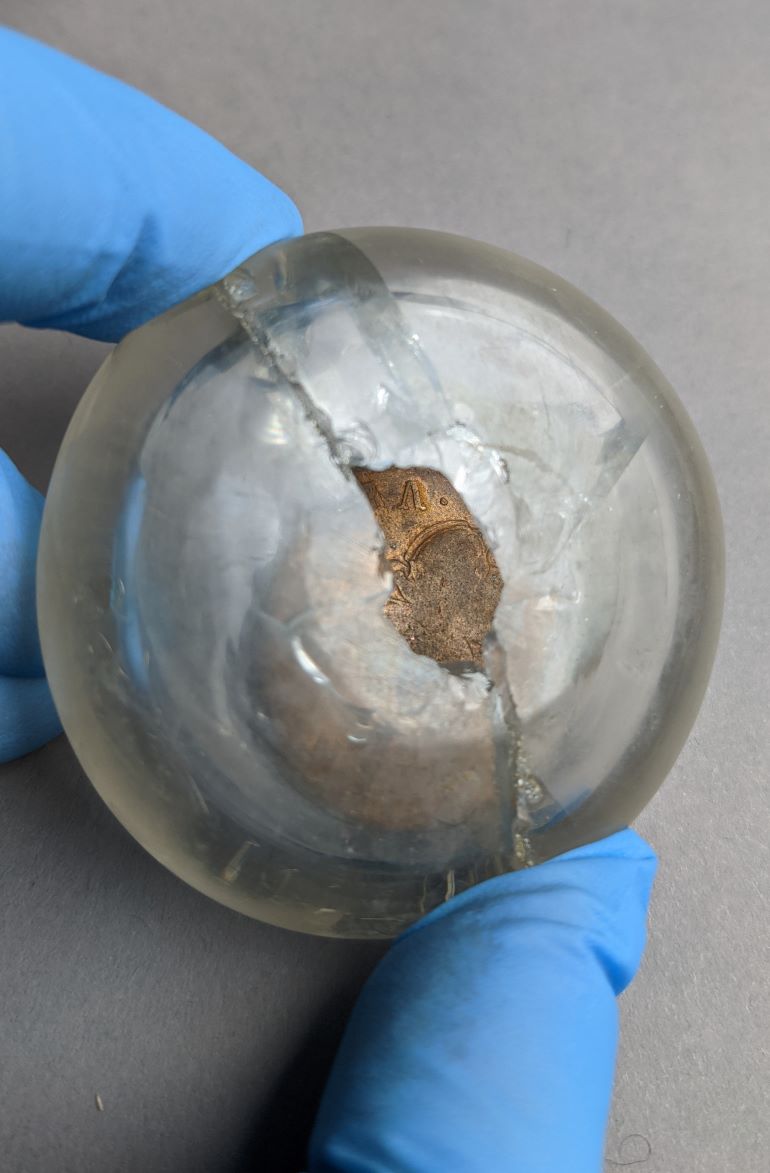

The foundation stone for the Bridewell was laid on 30th November 1791 accompanied by a grand procession and full masonic honours, and building work was completed in 1795. As part of the laying of the ground-breaking ceremony two glass time-capsules were laid into the foundations. One contained coins of the reign and the other local newspapers and names of city magistrates. In February 1883, when work was being undertaken at the Calton Jail site, workmen unearthed the Bridewell foundation stone and one of the time-capsules.

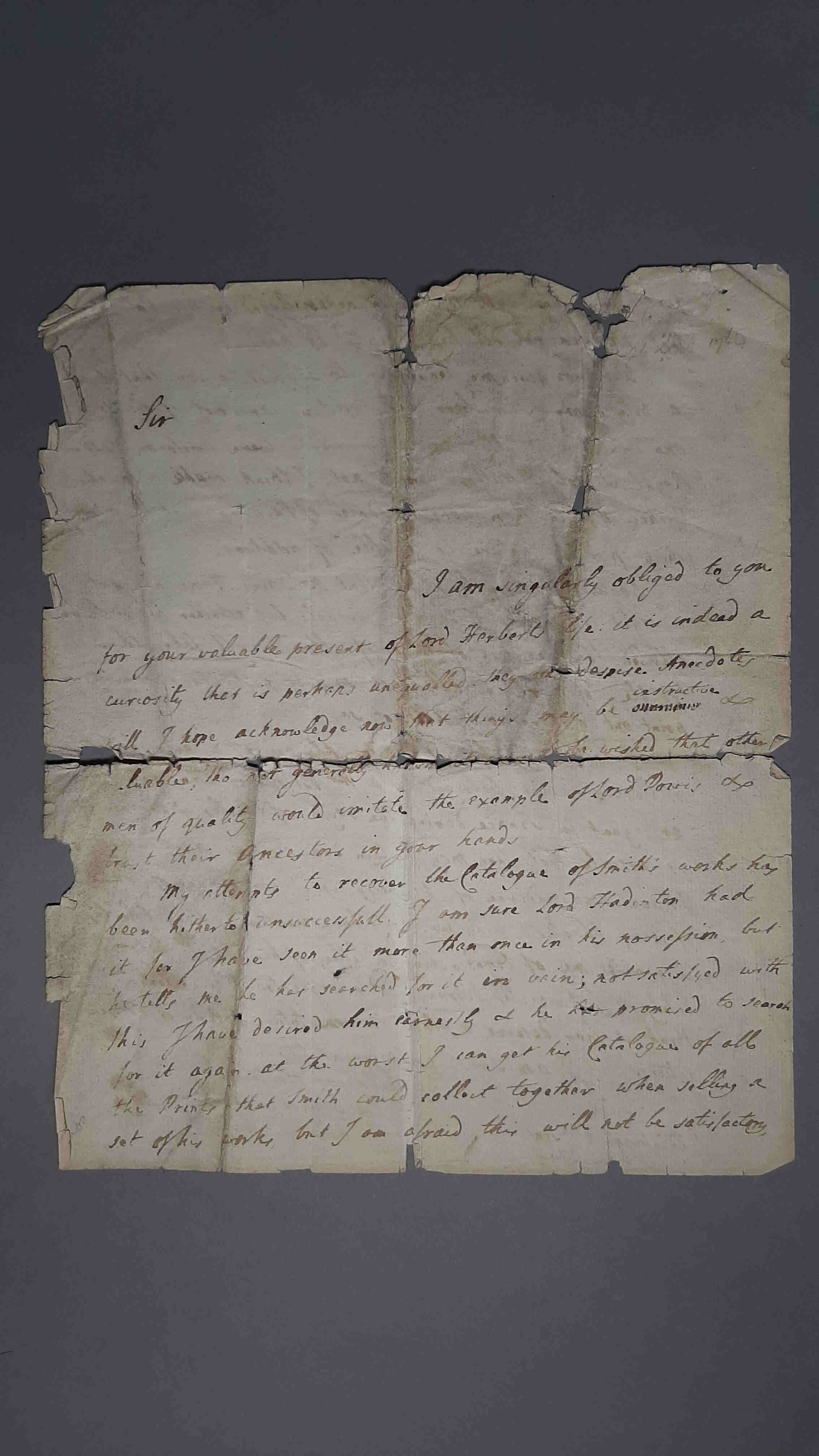

A handwritten letter in our collection from J. B. Collinson, architect, dated 8th February 1883, and signed by A. Beatson Bell, Chairman of H.M. Prison Commissions for Scotland, explains the circumstances when the time-capsule was discovered and states that the Earl of Roseberry, who was under-secretary of State for the Home Department, instructed that the stone and its contents were to be replaced. The stone and its contents were rediscovered when the Bridewell was demolished in the 1930s and at that point were acquired for our collection.

The letter refers to eleven, glass-encased coins, however, there are only seven in our collection and it is unknown what happened to the others. Some have survived in better condition than others. As far as we know, the other time-capsule has never been recovered.

The Bridewell was Scotland’s first ‘new’ penitentiary where facilities and treatment of prisoners were far removed from those of the dilapidated and overcrowded old Tolbooth. This new model prison put prisoners to work in activities such as spinning and weaving, and the sale of this work helped to pay for the prison. The Bridewell and its surrounding site were remodelled and extended throughout the 19th century, becoming part of the Calton Jail facility until the site closed in 1927 and all the buildings, except the Calton Jail Governor’s House, were demolished in 1935 to make way for the construction of St Andrew’s House.

You can see more images of the Bridewell and Calton Jail. from our collection online at www.capitalcollections.org.uk

Auld Reekie Retold is a major three-year project which connects objects, stories and people using Museums & Galleries Edinburgh’s collection of over 200,000 objects. Funded by the City of Edinburgh Council and Museums Galleries Scotland, the project brings together temporary Collections Assistants and permanent staff from across our venues. The Auld Reekie Retold team are recording and researching our objects, then showcasing their stories through online engagement with the public. We hope to spark conversations about our amazing collections and their hidden histories, gathering new insights for future exhibitions and events.

-

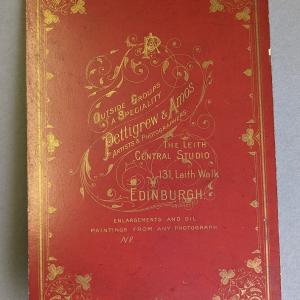

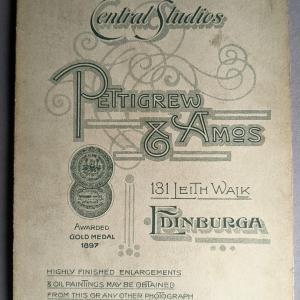

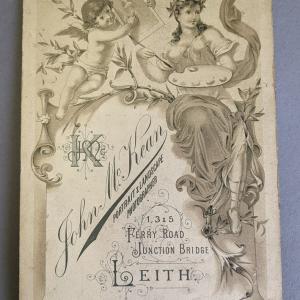

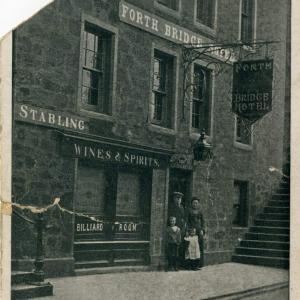

Welcome to the Auld Reekie Retold Podcast from Museums & Galleries Edinburgh. This is our fifth episode and today you’ll hear from Suzy Murray from the team working on the Auld Reekie Retold project. Suzy is going on an adventure to Leith today, and you can join her! Follow along on Our Town Stories using the interactive map to see the route and all the images she's discussing. The walk will start up at the Victoria Bridge and take you down to Elm Row. On the way Suzy will discuss photographs and photographic studios which help tell the story of Leith Walk and the surrounding areas. We have been creating the podcast from home, so please excuse any inconsistencies in the audio.

Follow the route and see all the images here on the Our Town Stories site.

You can get the podcast on most major podcast providers so look for Auld Reekie Retold to subscribe on your preferred platform. Listen here on soundcloud

Auld Reekie Retold is a major three year project which connects objects, stories and people using Museums & Galleries Edinburgh’s collection of over 200,000 objects. Funded by the City of Edinburgh Council and Museums Galleries Scotland, the project brings together temporary Collections Assistants and permanent staff from across our venues. The Auld Reekie Retold team are recording and researching our objects, then showcasing their stories through online engagement with the public. We hope to spark conversations about our amazing collections and their hidden histories, gathering new insights for future exhibitions and events.

-

4min Article

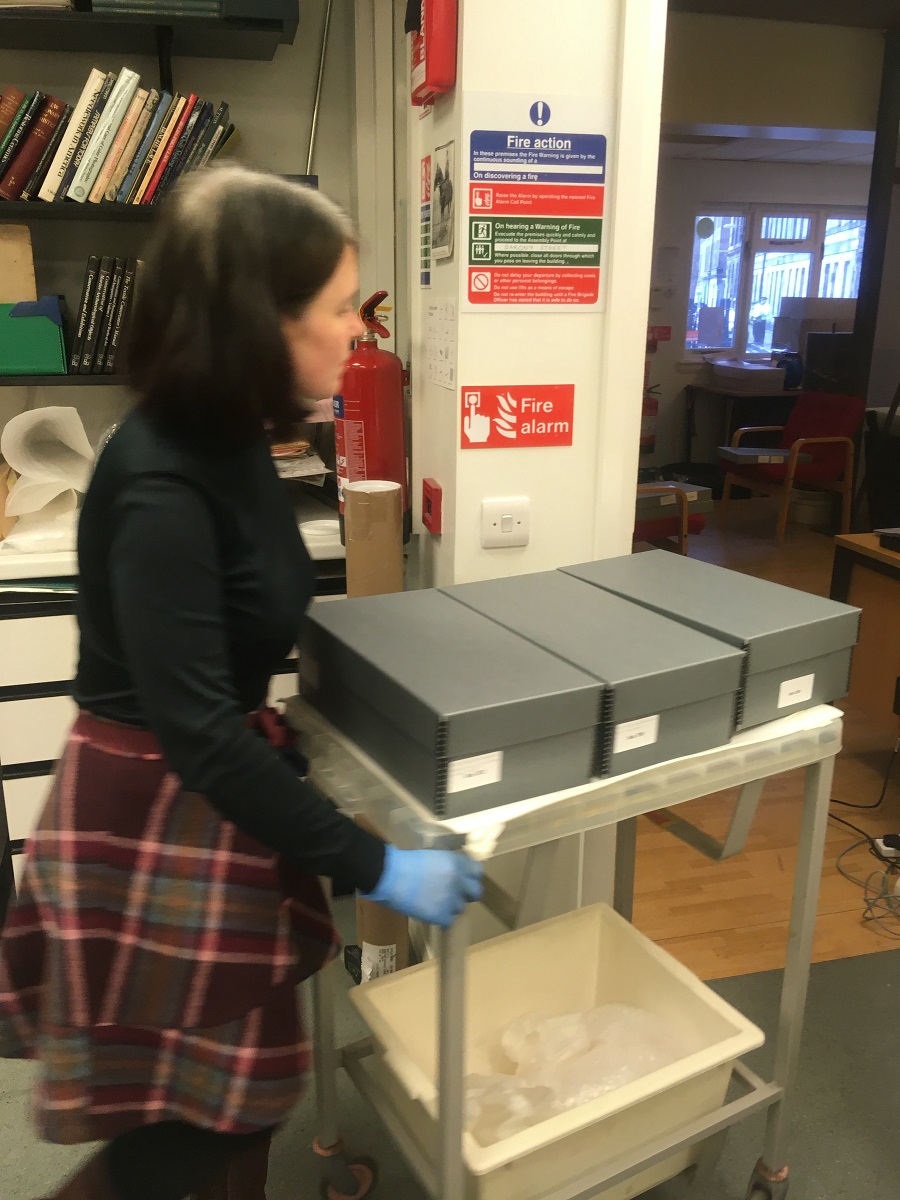

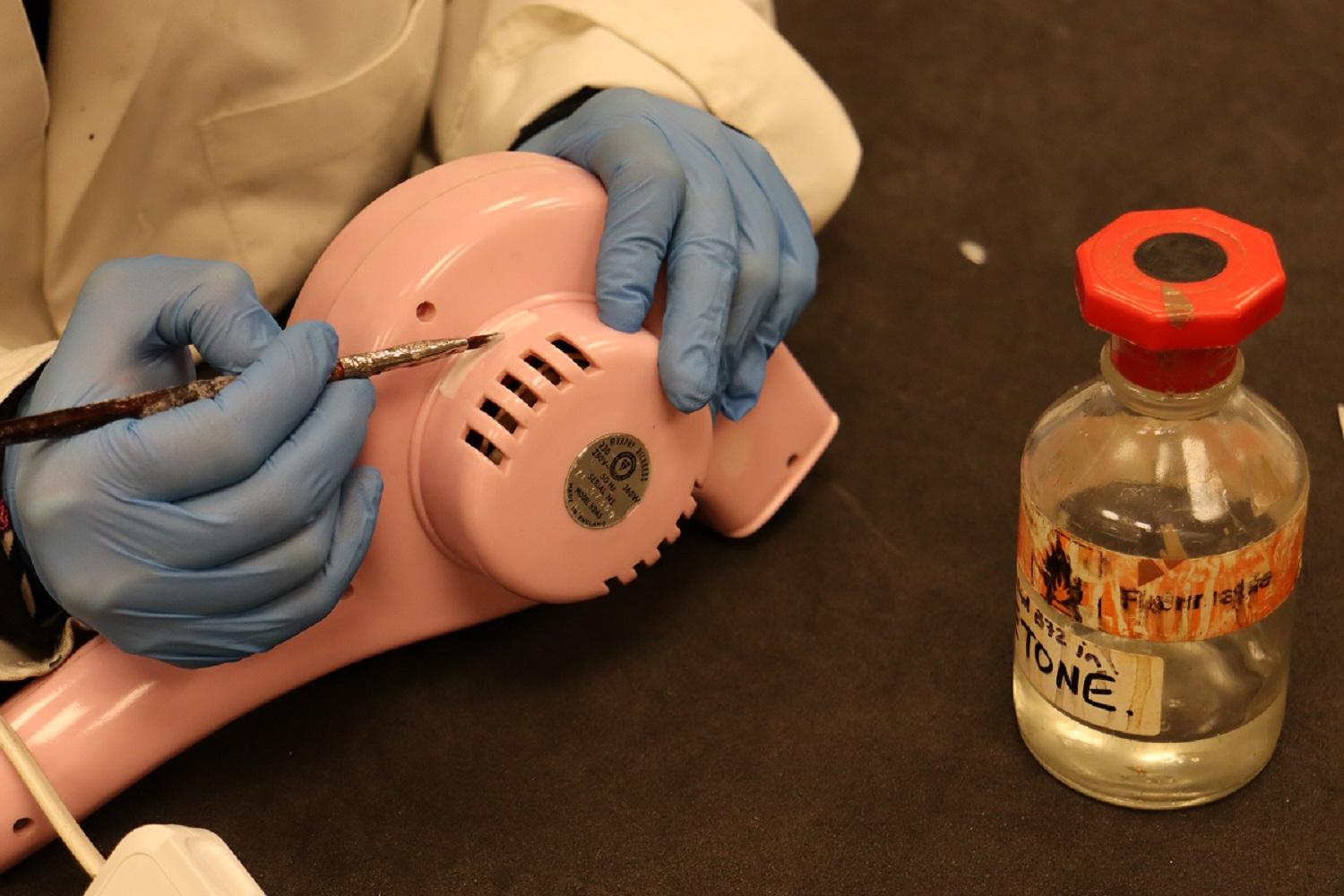

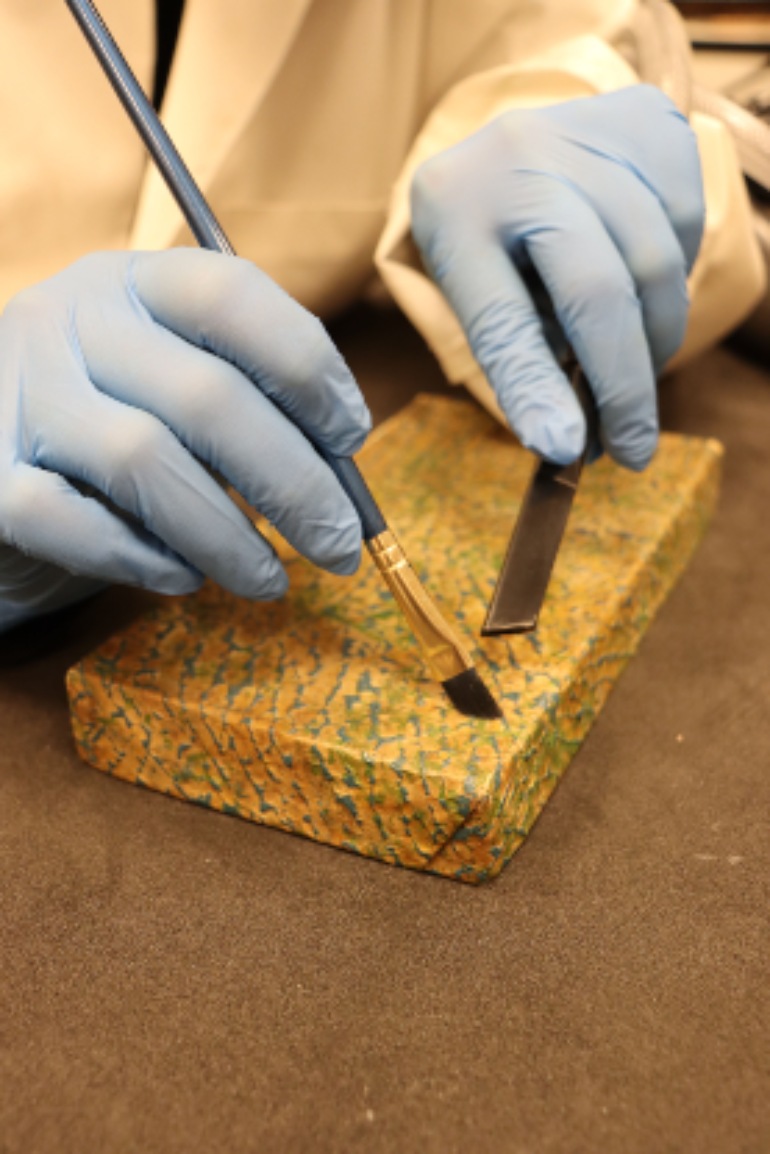

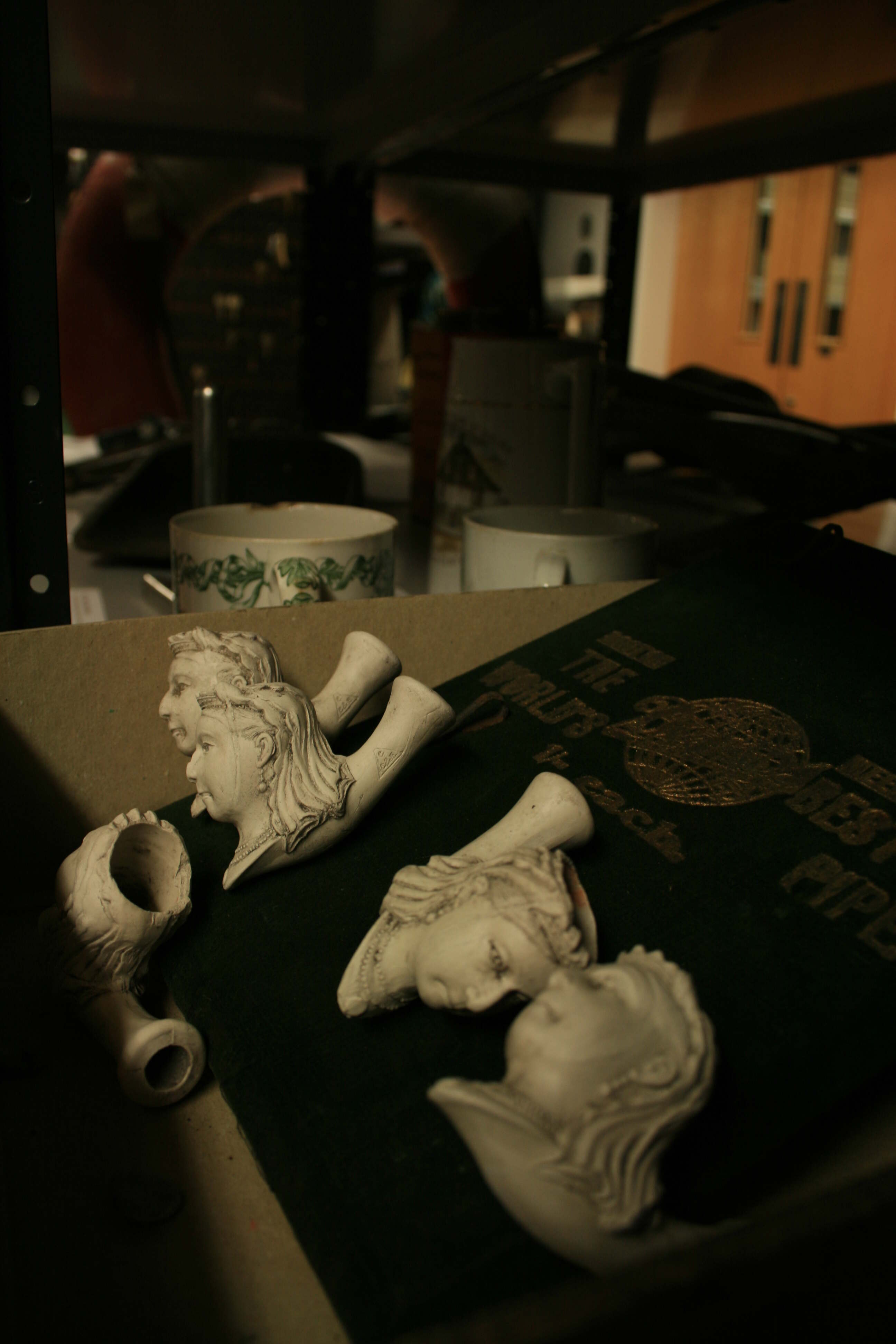

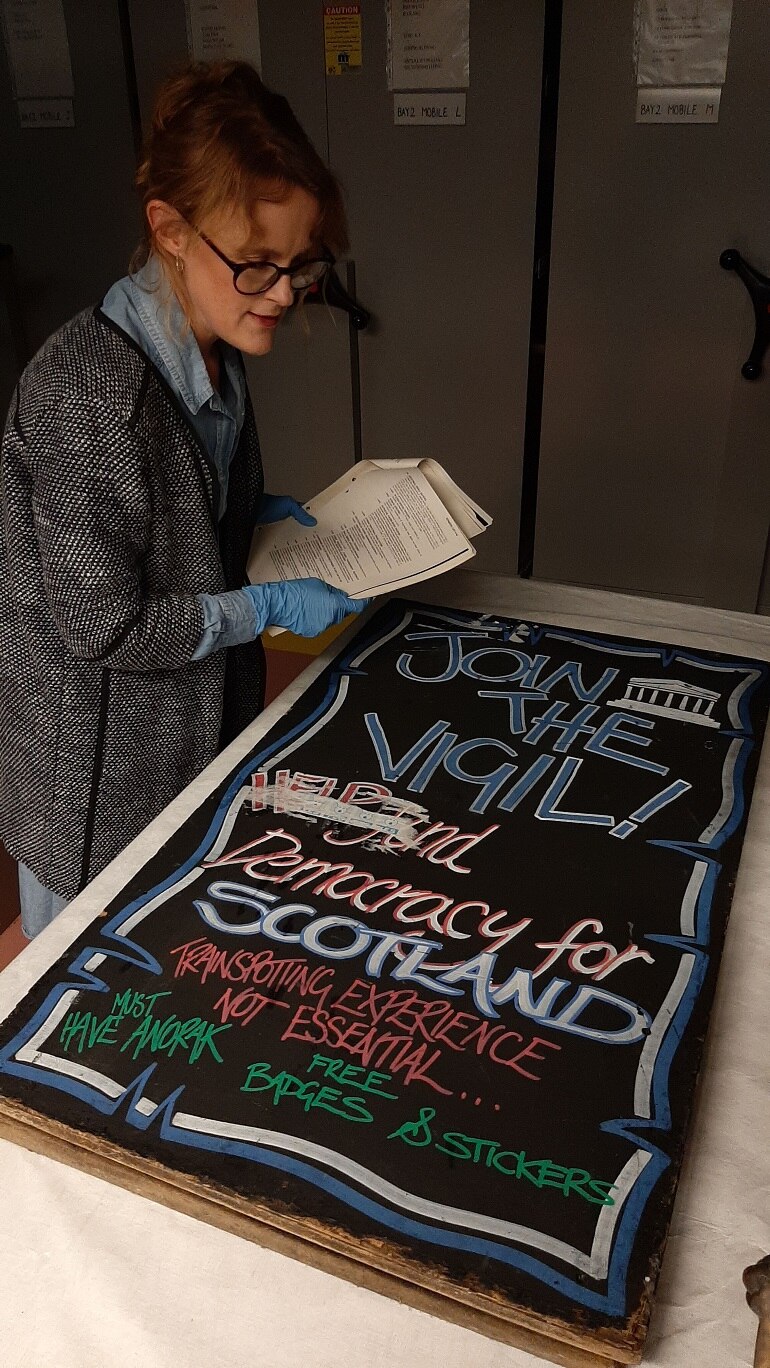

In this blog, Gwen Thomas, Collections Care Officer, gives an insight into how we look after the physical wellbeing of our collections.

Our museums and galleries look after a lot of different objects, from Paolozzi sculptures to Barbie dolls, 16th century documents to 21st century protest placards. But what does ‘looking after’ mean in practice? As Museums & Galleries Edinburgh’s Collections Care Officer, my job is to physically care for everything in our collection, and to support my colleagues to do the same. Care could mean making sure objects are safely and securely displayed in our museums; packing each object in the most suitable way in our collections store; or making sure that an object’s environment isn’t causing it any damage. This blog focuses on how an object’s environment can impact upon it, and how we intervene to maintain our amazing collections.

Invisible factors like light, UV, incorrect temperatures and high or low humidities need to be managed to prevent mould and insect outbreaks among our collections. These invisible factors may also cause fading, cracking and sagging in objects. It’s important to manage the environment in order to preserve objects for the future.

There are also times when we have to offer hands-on care to our objects, for example if they are dirty, have been attacked by insects, or have water damage. If there is a bigger problem, like a broken part or flaking paint, we usually have external specialist conservators treat the object. For day-to-day care, Museums & Galleries Edinburgh staff and volunteers carry out the work.

Before embarking on any treatment, we will visually check the object all over and write up any damage or problems that we can see. This is called a condition report, and we will do these for objects that we borrow, like this loaned artwork by Ian Hamilton Finlay, as well as for our own collections as part of Auld Reekie Retold. This process helps us track issues over time and identify new problems.

If an object is dusty or has other deposits on the surface, we will try to remove the dirt with a dry brush or a cloth first. If the object is fragile or made from an easily damaged material like silk or silver, we might use a soft brush made of pony hair, or smoke sponge, a rubber sponge which lifts dirt safely off delicate surfaces.

If possible – and it isn’t always, because all our museum buildings are historic and power sockets are never where you need them! – we try to brush dust directly into a vacuum cleaner with a small nozzle, so the dust is completely removed from the environment.

Sometimes when dirt has become very ingrained, or set into the surface of the object, we might have to use some water with a cotton wool swab to very gently remove it.

Water is never our first step, as it can cause more damage to an object than dust particles. If dirt or staining is really bad, we might consider using a solvent like white spirit or acetone. We will only use a chemical cleaning method, which includes water, if it is safe for the object. Acetone, for example, can cause plastics to melt, so we are unlikely to risk cleaning a plastic doll this way.

As well as dust, there are other reasons we might need to check, treat or clean objects. Mould, for example, can cause serious problems for a museum object, and is very difficult to permanently remove.

We have a lot of objects in our collection that are vulnerable to insect attack, such as carpet beetles or clothes moths – textiles, teddy bears, furniture and more. As we monitor for insect activity with sticky traps, we usually get an early warning if there are pests about. However, insect attacks can be quick and devastating.

When we learn that we might have an insect infestation, we check all the objects in the affected area thoroughly. We will clean them using a brush or smoke sponge to remove dust. If we find evidence of pest activity, like moth cases or frass (insect poo), we might freeze the object or treat it with a museum-grade pesticide, to eliminate the infestation. When objects are frozen, they are double wrapped and sealed in polythene, with some extra acid free tissue inside the package as a buffer. Depending on how cold the freezer temperature is, objects are frozen for between 48 hours and two weeks. We then let the objects defrost slowly before unpacking and checking them. We only freeze organic materials, like wool, silk and wood. Some things that are particularly fragile, or have very thin layers that could be split by the ice crystals, would not be frozen to avoid more damage.

Checking and cleaning museum objects isn’t always easy, because of how varied our collections are. A lot of things are in display cases, or out on open display at Lauriston Castle which can mean tiptoeing around inside without knocking anything over!

Working hands on with museum collections, and making sure they have the best environment and care possible, may be tricky and time consuming, but it is incredibly rewarding. Our care and attention means these objects will be around for future generations of museum visitors to enjoy.

You can see more items from our collection online on the Capital Collections website

You can find out more about how we store the objects in our collection on the Stories section of our website.

Auld Reekie Retold is a major three year project which connects objects, stories and people using Museums & Galleries Edinburgh’s collection of over 200,000 objects. Funded by the City of Edinburgh Council and Museums Galleries Scotland, the project brings together temporary Collections Assistants and permanent staff from across our venues. The Auld Reekie Retold team are recording and researching our objects, then showcasing their stories through online engagement with the public. We hope to spark conversations about our amazing collections and their hidden histories, gathering new insights for future exhibitions and events.

-

3min Article

Our last Queensferry blog looked at the Ferry Fair – an annual celebration held in August in South Queensferry. In this new blog, history curator Anna MacQuarrie will look at one particular tradition that is now part of the Fair, though has a mysterious history all of its own. If you were to visit South Queensferry (or ‘The Ferry’ to those in the know) on the second Friday in August, then you might cross paths with a strange, burr-covered figure, walking through the village to cries of 'Hip hip hooray, it’s the Burryman’s day!'. But just who is this mysterious and other-worldly figure?

The strange figure emerges on the same day, at the same time, from the same place each year: 9am on the second Friday in August, from the Stag Head Hotel on the High Street. Flanked by two minders and a third person out in front with a ringing bell, leading the hip hip hooray cries, out comes The Burryman.

An ancient folk tradition, no one is certain how, when, or why the Burryman first came to be. There are enough archive references, and cultural memory, to know that some version of this tradition has taken place for many hundreds of years in South Queensferry. Some say he’s related to other folk traditions found across the British Isles, celebrating Harvest or the changing of the seasons. We likely won’t ever know for certain, and we think that mystery is part of his appeal.

So, what about that outfit he’s wearing? Using the natural velcro-like qualities of the burdock plant, tens of thousands of individual burrs are collected each year by the Burryman himself, and his family, to create his outfit. They are made into large sections of material, which are then attached onto a bodysuit and balaclava to create the outfit. Flowers adorn his crown (later given as a gift to a worthy member of the community) and the staffs used to help support him on his walk. It’s a privilege for any person to hold the role of the Burryman, as it is being part of the team dressing him each year.

While it may seem obvious that he is perhaps named after the burrdock plant, debate has raged over the precise meaning of the Burryman's name. Some say it reflects being “a man of the Burgh”. Even whether he is the Burry Man or Burryman is debated and varies over time. As with so much to do with this tradition, we’ll probably never know for sure one way or the other.

The Burryman's tour throughout the Ferry involves stopping off at the homes and premises of important local people, receiving a dram of whisky at each stop. At around 6pm, he’ll finally finish up, back at the waterfront. It’s a long, hard day (he walks around 9 miles) but each year a lot of money is raised for charity with his entourage collecting donations from onlookers and supporters. Lots of visitors to Queensferry Museum ask about the practicalities of being the Burryman, and consuming all that liquid throughout the day. We don’t dwell on this, and let that also remain a mystery known only the Burryman himself.

We’re really proud to help celebrate and preserve this important old tradition, with our permanent displays in Queensferry Museum all about the Ferry Fair and a life-size model of the Burryman himself on display. There is no real equivalent to seeing him in person, and experiencing one of Scotland’s most intriguing folk traditions still celebrated. We hope to see you there. Once more for luck: hip hip hooray, it’s the Burryman’s day!

You can see more about South Queensferry from our collection online at www.capitalcollections.org.uk

You can find out more about the Ferry Fair here

-

In this blog, Susan Gardner, curator at the Museum of Childhood, explores the story of geologist and writer Hugh Miller, his family, and their links with Edinburgh.

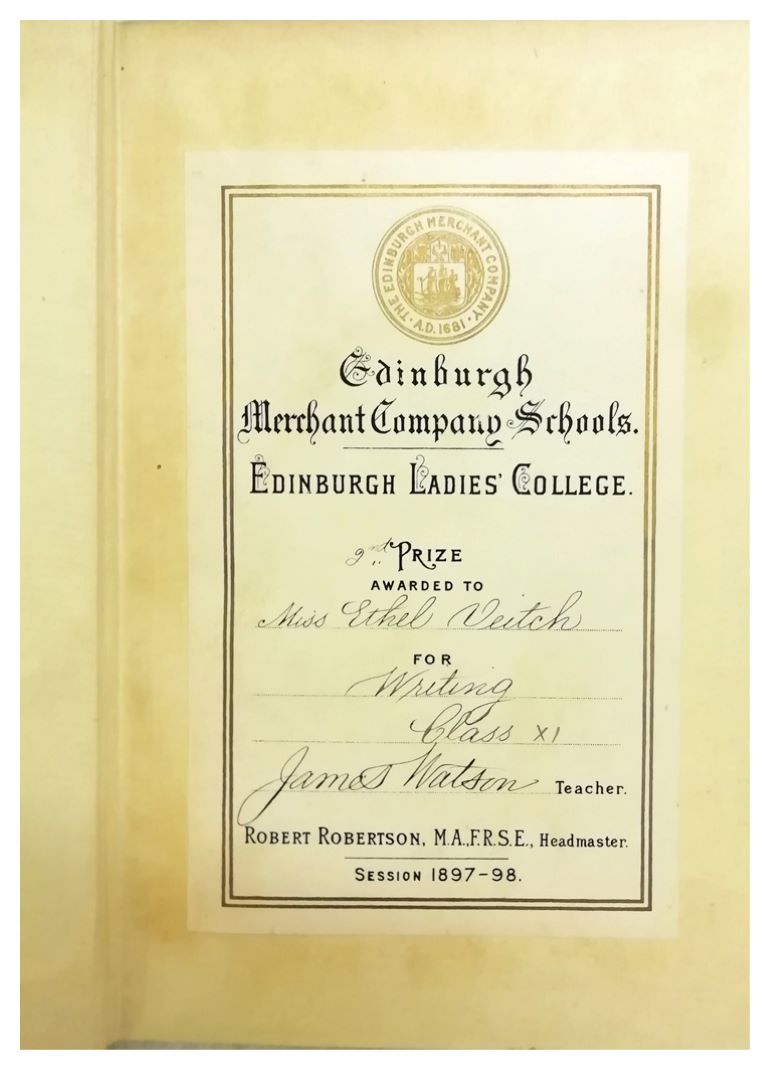

When you begin researching a museum object, it can sometimes lead you into unexpected places. This was the case recently when I began looking at the Museum of Childhood’s education collection. A large part of the collection deals with Edinburgh schools and I was looking particularly at material from Edinburgh Ladies College. This was a private school, founded in 1694 as the Merchant Maiden Hospital, for the daughters of Edinburgh burgesses. In 1870 it was re-named the Edinburgh Educational Institution for Girls and this was changed again in 1889 to Edinburgh Ladies College. The school still exists today and, since 1944, has been known as The Mary Erskine School.

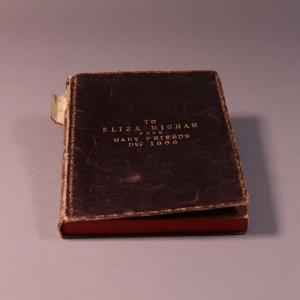

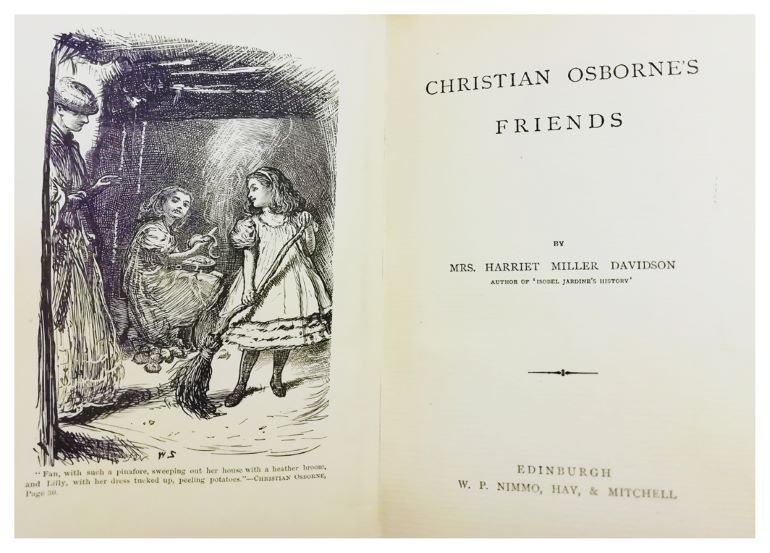

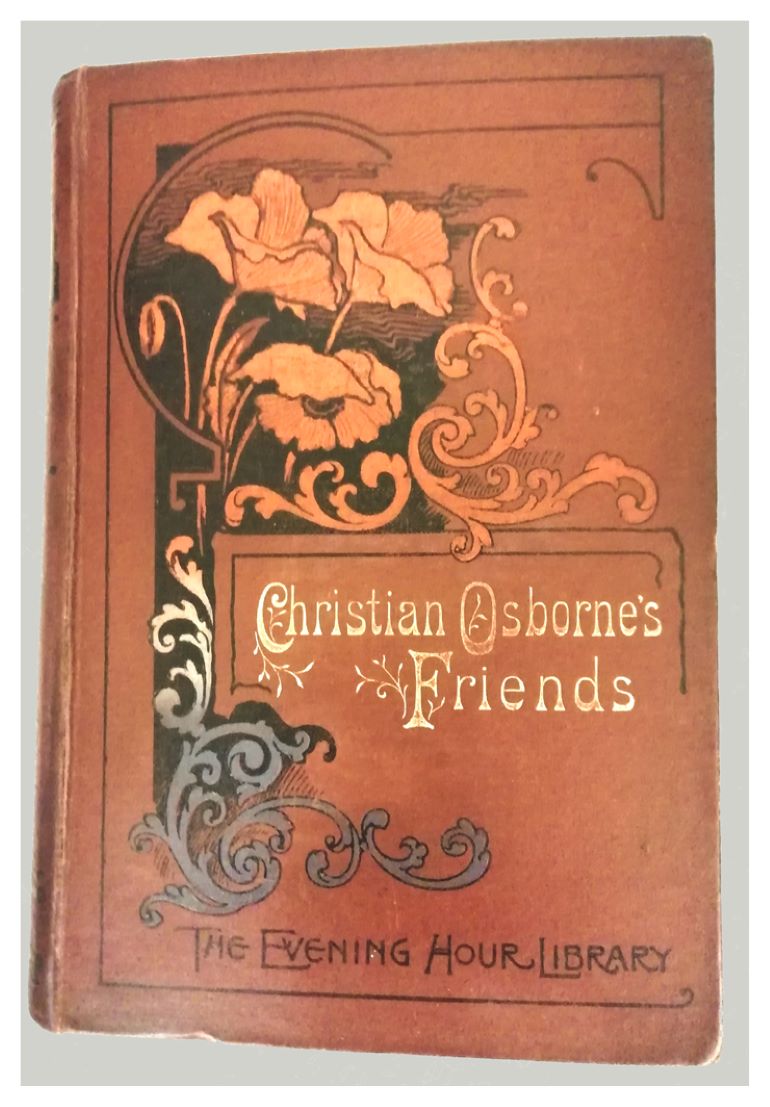

One of the objects in the education collection is a book given to Ethel Veitch, a pupil at Edinburgh Ladies College, for her efforts in Writing Class during 1897-98. It is a novel called Christian Osborne’s Friends written by Mrs Harriet Miller Davidson and first published in Edinburgh by William P. Nimmo in 1869. I had never heard of Harriet Miller Davidson but a quick online search revealed that she was one of the children of Hugh Miller, a much more familiar name.

Hugh Miller has been described by Dr James Robertson, author of And The Land Lay Still, as one of the most extraordinary minds that Scotland has produced. In the introduction to a 2002 edition of Hugh Miller's My Schools and Schoolmasters, Robertson says:

“He rose, if not from absolute poverty, certainly from a modest background, to become both a specialist in the field of geology and a generalist in the wider literary world, covering, as writer and editor, subjects as diverse as poetry, folklore, science, education, religion, history and travel; while in his working life he was a stonemason, banking accountant, journalist, editor, lecturer and defender of Christianity against the evolutionists. His prodigious output made him among the best-known of Victorian literary figures, admired by the likes of Thomas Carlyle, Charles Dickens and John Ruskin.”

The last years of Miller’s life were spent in Portobello, Edinburgh where, tragically, he killed himself with a revolver in 1856. He had been suffering from brain disease which he described as a burning agony. A crowd of around 4000 lined the streets for his funeral procession from Portobello to the Grange Cemetery in respect of a local man with an international reputation.

Miller’s daughter, Harriet, was seventeen at the time of her father’s death and, according to the Dictionary of National Biography, it was a shock from which she never completely recovered. In later years she married a clergyman and moved with him to Australia. Her books, Christian Osborne’s Friends and Isobel Jardine's History, a temperance tale, remained popular and were often given to young girls as school prizes or presents.

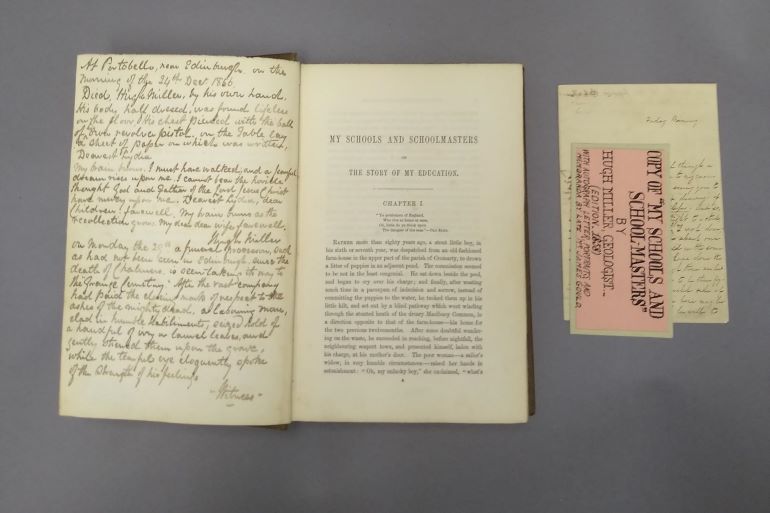

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh also has two copies of one of Hugh Miller’s books, My Schools and Schoolmasters, or The Story of my Education, written in 1853-54. It is an account of his life aimed particularly at working men, with the intention of “rousing the humble classes to the important work of self-culture and self-government – and incidentally to throw light, for those above them, on their conditions of living.” (W. M. Mackenzie, editor). A more intriguing object in the collection is a steel spectacle case believed to have belonged to Hugh Miller. It was donated to the museums in 1909 and is among the earliest exhibits in the collection. Its authenticity was verified by James Anderson in a handwritten note which says “This old spectacle case was the property of Hugh Miller the geologist and was left by him during his visit to Cromarty in 1844. It is the only momento of my late lamented friend I have”.

An image of Hugh Miller that will be familiar to many can be found in Museums & Galleries Edinburgh’s Fine Art collection at the City Art Centre. This calotype photograph was taken by the famous photographic partnership of Hill and Adamson and was among 35 calotype prints acquired by the City Art Centre in 1977. It was an important addition to the fine art collection, representing not only photographic history but some influential Victorian figures, not least, Hugh Miller. Fine Art Curator Helen Scott says “Miller is shown in the guise of a stonemason, leaning against a gravestone with a set of carving tools. This is partly in reference to his early training as a stonemason, and partly on a metaphorical level to suggest the steadfastness of his commitment to his religious and philosophical principles”.

So, a once popular but now long-forgotten Victorian novel has taken me on a journey through girls’ education in Edinburgh, a rags-to-riches story of self-improvement, tragic suicide at Edinburgh’s seaside and pioneering photography. The breadth of our collections is endlessly fascinating. Where will they lead next?

Recent reappraisal of Hugh Miller's views and works: In response to the Black Lives Matter movement, the organisers of the Hugh Miller Writing Competition commissioned some further research into Hugh Miller’s life. This uncovered racist views which were published in Miller’s book, The Testimony of the Rocks, in 1857. For further information see https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-highlands-islands-55258085

Auld Reekie Retold

Auld Reekie Retold is a major three year project which connects objects, stories and people using Museums & Galleries Edinburgh’s collection of over 200,000 objects. Funded by the City of Edinburgh Council and Museums Galleries Scotland, the project brings together temporary Collections Assistants and permanent staff from across our venues. The Auld Reekie Retold team are recording and researching our objects, then showcasing their stories through online engagement with the public. We hope to spark conversations about our amazing collections and their hidden histories, gathering new insights for future exhibitions and events.

-

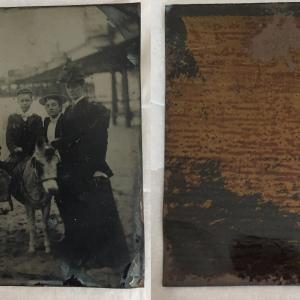

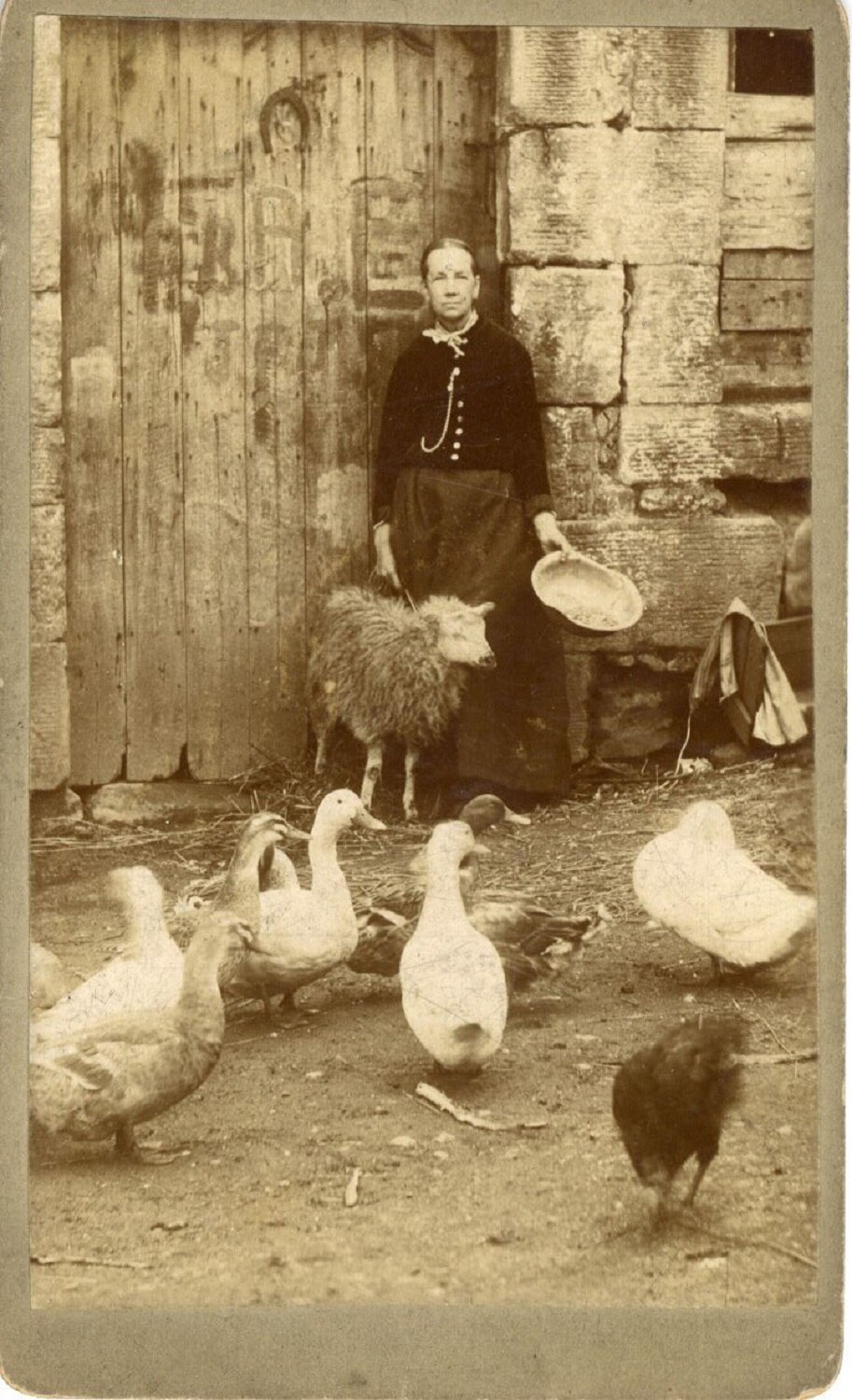

In this Auld Reekie Retold blog, Decorative Arts Curator Helen Edwards has been looking at an intriguing box of photographs. The photographs were found in an old house in Newhaven in the early 1970s, shortly before it was due to be demolished. The donor kept them for many years before donating them to Museums & Galleries Edinburgh. Helen’s challenge was to find out more about these images, but with only scant information to help the search, has it been possible to reveal the stories behind the photographs?

Some of the mystery photographs found in the Newhaven house had names written on the back, although I think these were added later and are not always correct. Some were marked Klaundyke and others Parliament Square. Klaundyke was a local name for tenements on Newhaven Main Street at the corner with Fishmarket Square. They were built during the Canadian Gold Rush and nicknamed ‘Klaundyke’ after Klondike in Canada. Parliament Square referred to the area around the Assembly Rooms in Leith.

Census returns are a good way of tying family names to specific places. The name Grace Crawford came up most frequently. From looking at the photographs I thought she might have been born in about 1900 so I looked first at the 1901 census. Once I had tracked her down, I could then use records from other years to fill out her story.

Grace’s grandfather was William Crawford. He was born in Douglas in Lanarkshire in 1842. According to the 1881 Census he was a general porter and was married to Margaret Begg who had been born in Newhaven in 1845. They were living at 2 Parliament Square, North Leith and had three children all born in Newhaven - Robert in 1869, Andrew in 1871 and John in 1875.

By the time of the 1891 census, the family were living at 16 Parliament Square. Their eldest son Robert had probably left home as he was not listed, although as census returns are just a snapshot of a single night, he may just not have been at home. Andrew was aged 20 and a seaman, John was 15 but had no occupation listed. It is John who we are most interested in, because he was Grace’s father.

John appears again in the 1901 census. By then he was 26 and married with children of his own. John was listed as a general labourer. His wife Jane (Jean) Sommerville was 25 and they were living at 44 James Street in North Leith. They had three children - Margaret (Maggie) aged 4, Grace aged 2 and William aged 1 month.

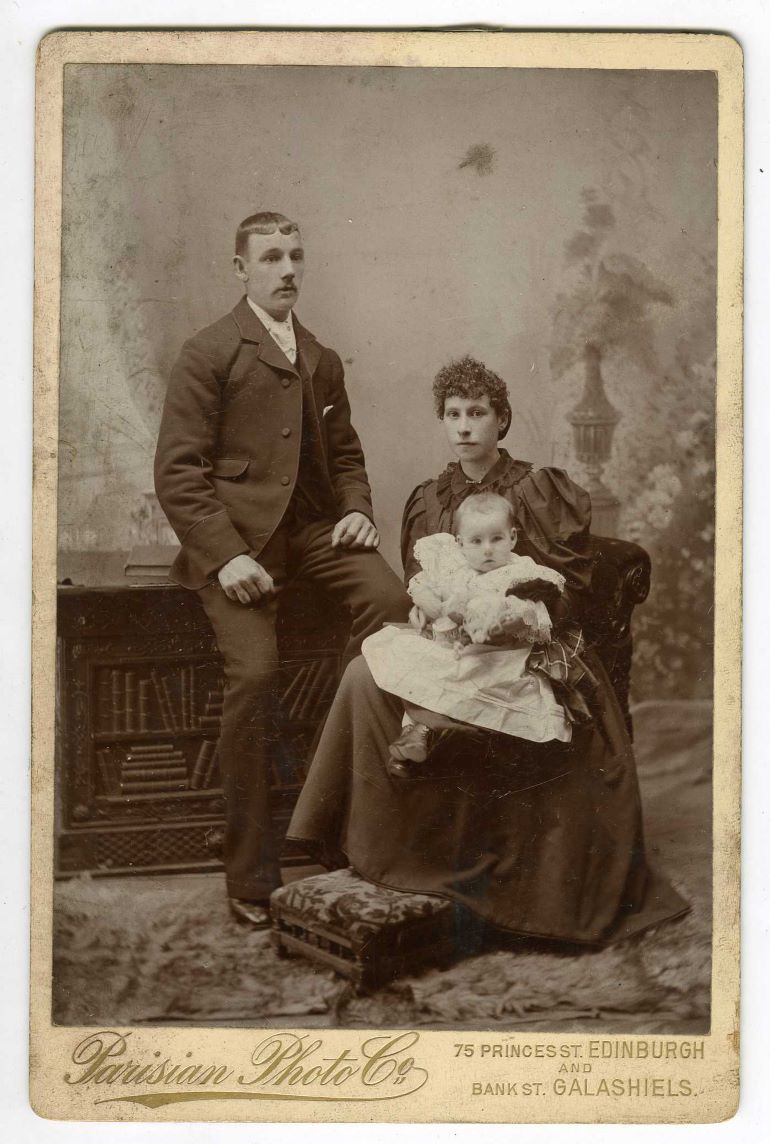

By comparing the people in some of the named photographs I was able to put possible identities to some of the people in the other images. I think this one is Grace and William and was taken in about 1901 at the Parisian Photo Studio, which was on the corner of Princes Street and Hanover Street in Edinburgh.

This may be another image of William as a baby but taken a little later than the one of William and Grace as he looks slightly older.

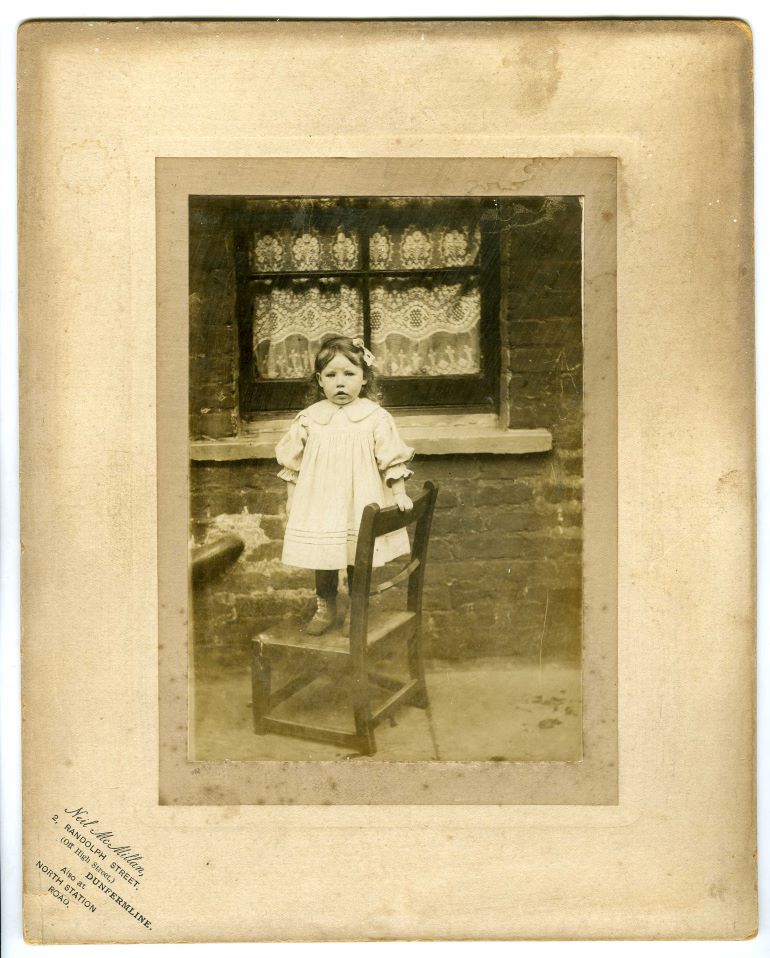

There is image which looks like Grace as a toddler, and although it was taken by a photographer from Dunfermline it looks very much like Grace.

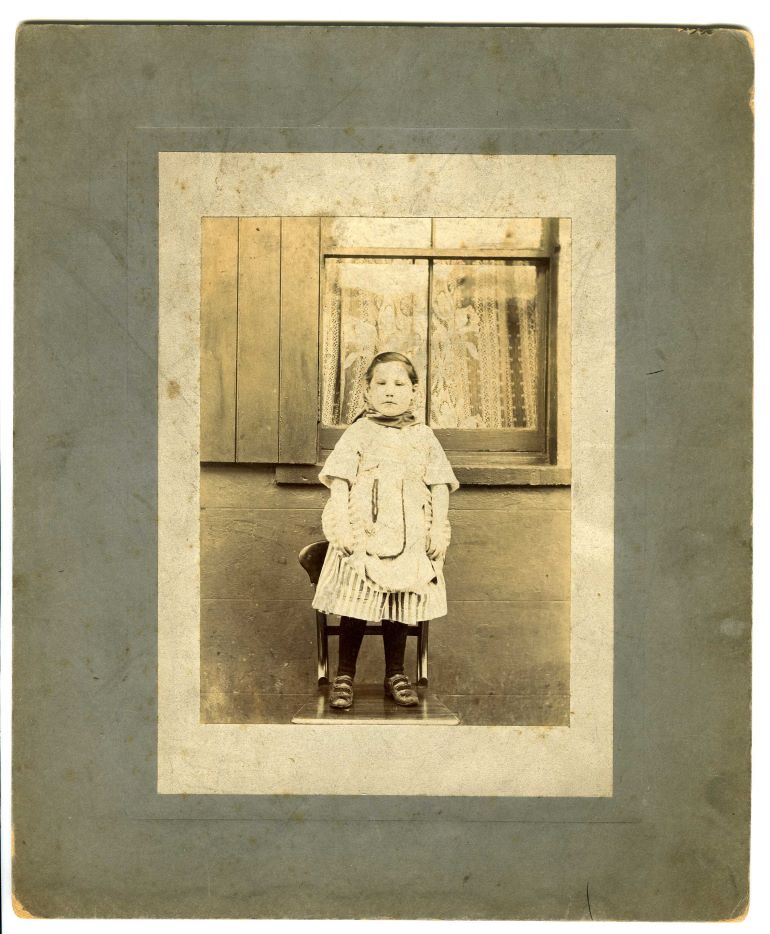

This may be Grace’s older sister Maggie aged about four and wearing a fishwives’ costume.

There are other photographs of Grace and Maggie in Fishwives costumes. They were probably dressed up for one of the Newhaven Gala days, which were held each year.

Other photographs show them with their brothers William and Jimmy who are dressed in fishermen’s jerseys, although these were taken in a photographic studio as they have painted background scenes. These may have been for other Newhaven Gala days. Part of the celebrations included children dressing up in traditional fishwive’s and fishermen’s costumes.

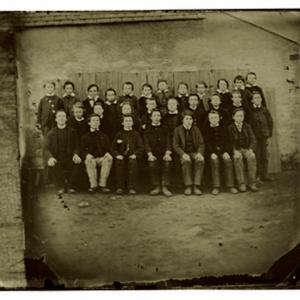

We also have Grace and Maggie’s school photographs. These were taken by Thomas Johnstone Kelly who had a studio at Ferry Road, Leith between 1899 and 1910. From the ages of the children I think these were taken in about 1907. Maggie’s photograph also shows her class teacher, possibly Miss Don. Research into school registers may reveal more names.

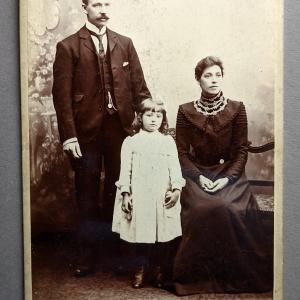

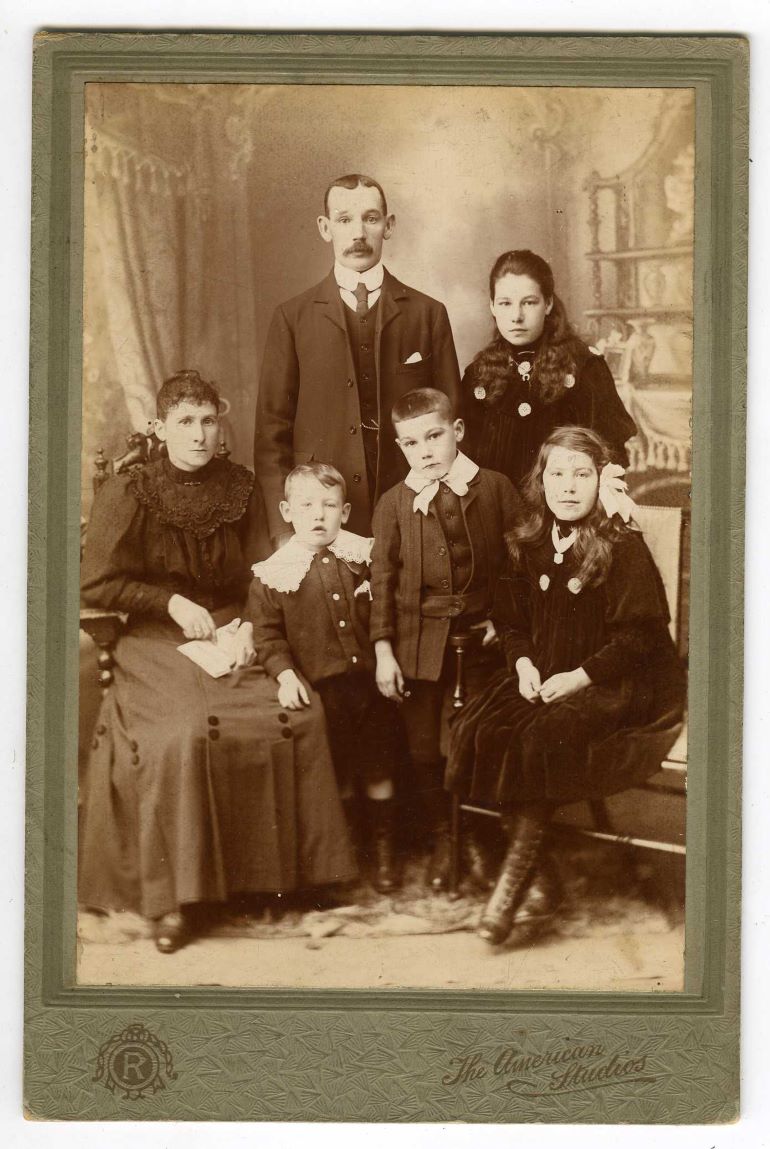

The 1911 census lists the Crawford family as still living at 44 James Street. By then John and Jane had five children. Maggie was 14, Grace 12, William 10, James (Jimmy) 5 and Jane (Jean) was 8 months. This photograph of the family was probably taken in about 1908 as it does not include Jane. It was taken at the American Studios. They had a photographic studio at 39 South Bridge, Edinburgh between 1908 and 1919.

This image was taken a few years earlier, probably in 1905 and shows Maggie, Grace, William and Jimmy.

These two images of Maggie and Grace were probably taken in about 1911.

Other images show Grace as she grows from young girl to young woman. Fashions and hairstyles change and life too must have changed so much in this period moving from the days before World War 1 to the 1920s.

This image of Children on the seashore, perhaps at Newhaven or at Portobello, may also be of some of Crawford family. I think the girl second from the right may be Maggie and Grace’s younger sister Jean.

Looking though all the photographs it was difficult to tie all the ages and names together which made me think some of them had been incorrectly labelled. These two photographs seem to have been taken at the same time, in the same studio and both women seem to be of a similar age. They are labelled Jean and Grace, but Grace was 12 years older than Jean.

Initially, I wondered if the photographs were Maggie or Grace’s children, but this did not make sense either. Then I realised that there could simply be a gap of 15 years or more between the siblings and a younger sister born after Jean could be the explanation for these images. As Census returns are only made every 10 years any younger siblings will not show up until the 1921 Census is released and for that we have must wait until January 2022.

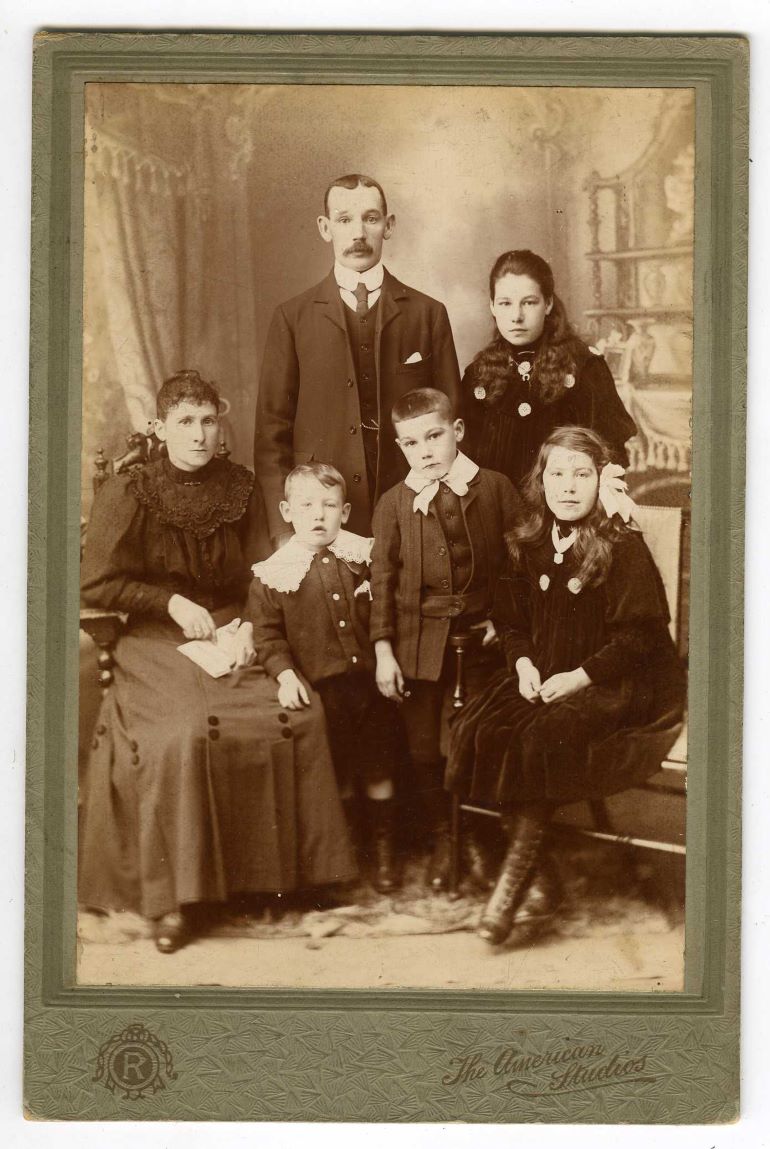

This may be an image of Jean or perhaps a younger sister. It was taken at a photography studio in Waverley Station Edinburgh in 1918 .

This image may also include some of the younger Crawford children. The girl standing in the centre at the back holding a ball is probably Jean and her younger sister may be standing with her arms folded in the centre of the row below. Look more closely and you can see other children holding a cricket bat, skipping rope and a bicycle wheel. The boy on the right may be Walter Liston and the photograph may be of children from North Fort Street School.

There were many other photographs in the box and it is my guess that they all relate to the Crawford family. Sadly, we may never know who they all were, but at least for Maggie, Grace, and their family I have been able to find out a little about them - only the bare bones of their story, but who knows perhaps this blog with spark some memories and we can add to their history?

The story does not end here, however. Read the sequel to find out what happened next, and how we learnt a lot more about Maggie and Grace.

-

3min Article

In this blog, Collections Assistant Gabriella Lawrie explores the story of Portobello bathing pool.

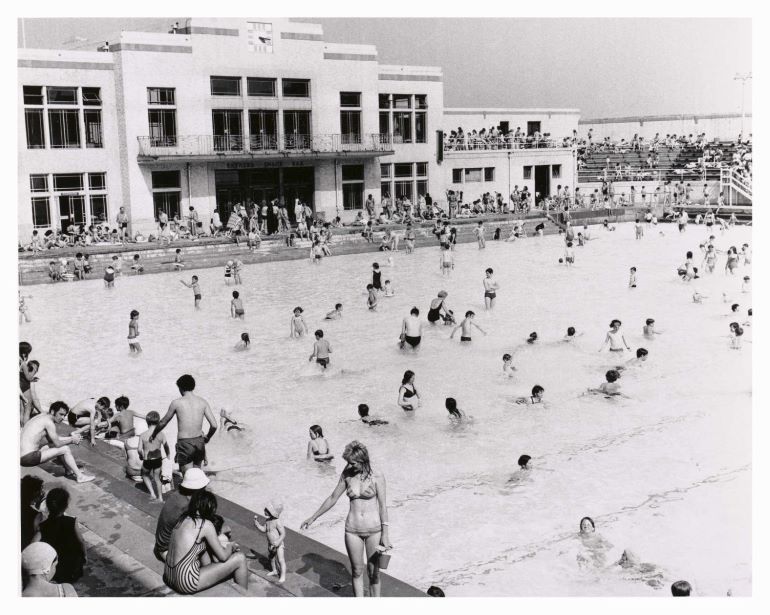

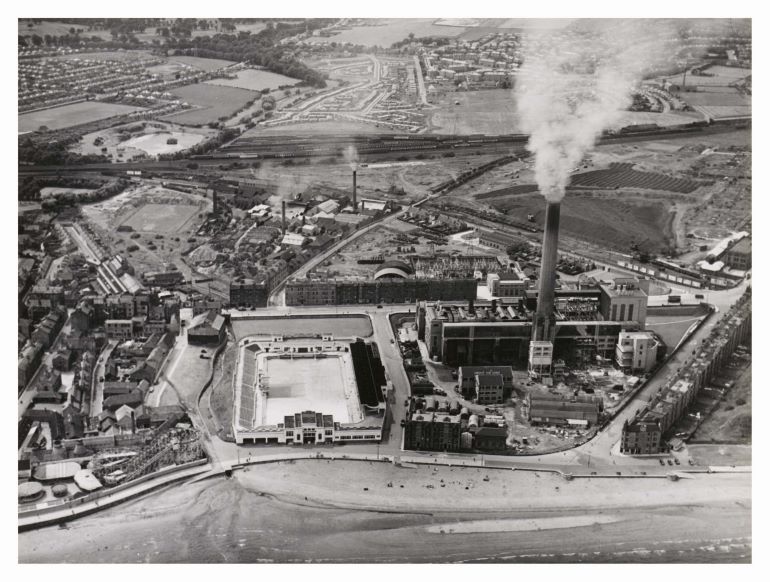

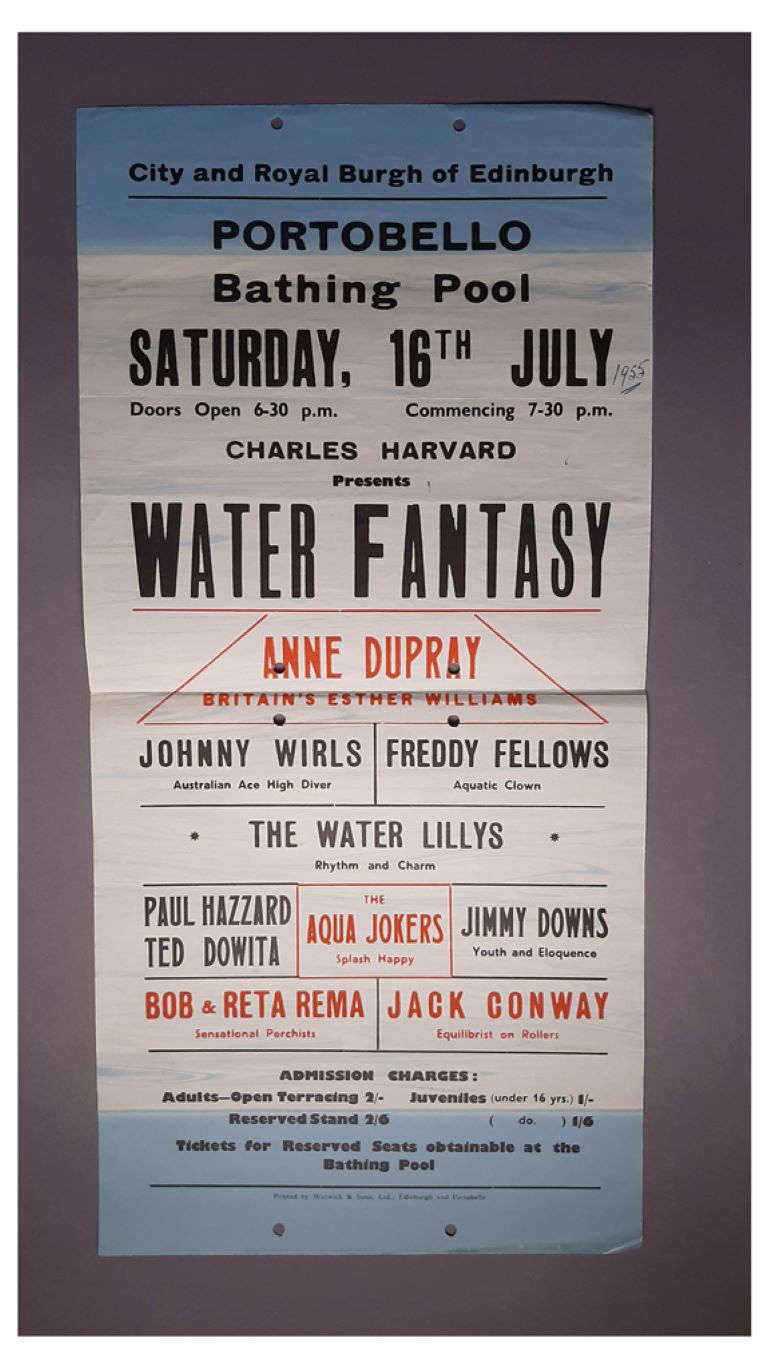

Portobello bathing pool was one of Edinburgh’s leading attractions for over 40 years with its Art Deco design, high diving boards, and outdoor heated pool. It was also the first of its kind in Scotland to install a wave machine.

Originally known as Figgate Muir, Portobello was once an expanse of moorland used as pasture for cattle by the monks of Holyrood Abbey. In 1742, veteran seaman George Hamilton built a cottage on what is now the High Street and named it Portobello Hut in honour of the capture of Porto Bello, Panama in 1739, for which he served under Vice Admiral Edward Vernon. By 1753 other houses had been built around it and the area became known as Portobello.

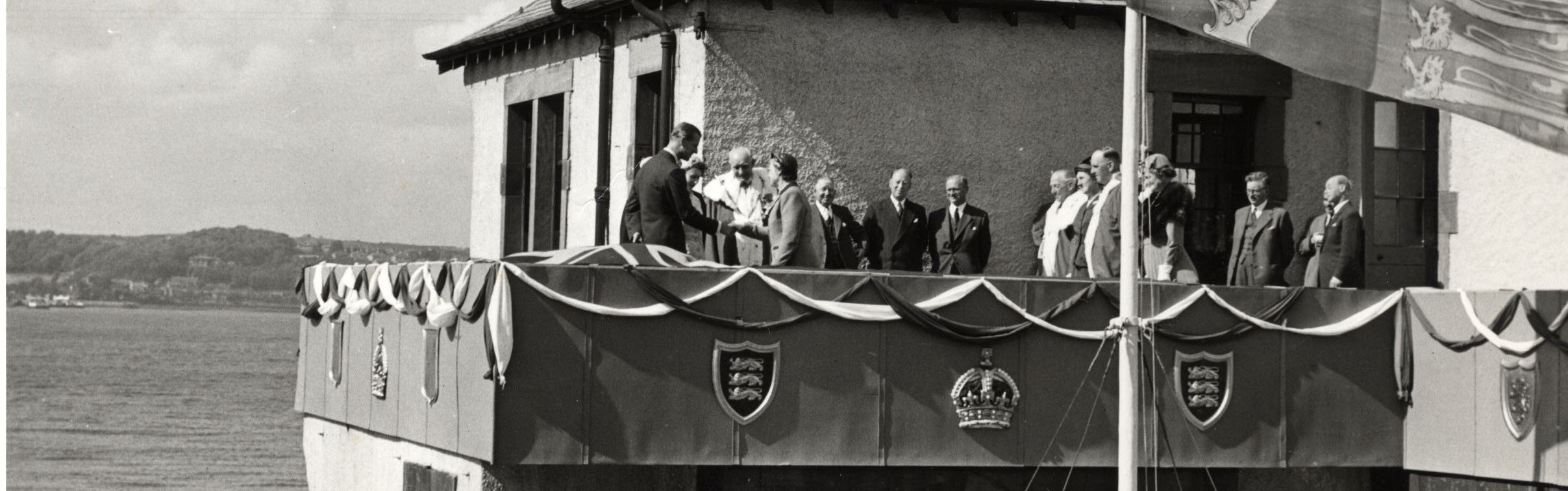

On the 30th May 1936 Portobello Bathing Pool was officially opened to the public by the Lord Provost Sir Louis Stewart Gumley. It was the largest of its kind in Europe and able to seat 6,000 spectators and accommodate 1,300 bathers. Upon opening it made a big splash, attracting many visitors and swimming enthusiasts from across the UK. A whopping 10,000 visitors attended the opening ceremony despite the bouts of torrential rain! Queues to gain entry would often stretch the length of Westbank Street and a ‘one in, one out’ policy was eventually adopted for the sunniest days when visitor numbers were at their highest.

The installation of an artificial wave machine that could generate waves as high as three feet, and in three different directions, made Portobello pool one of the jewels in the City’s crown. The pool became the perfect day out for a family, bringing in 290,000 bathers and almost 500,000 spectators in its first open season. It wasn’t just Edinburgh residents and holiday makers enjoying the wave machine, but also the Royal Navy, who sent troops to the pool to test out the effectiveness of their sea-sickness tablets in 1951.

One of the pool’s many unique selling points was the heated water, allowing the pool to be open from the month of May through to September every year until the outbreak of World War II in 1939. Construction on a site next to the coal-fired Portobello Power Station meant the pool could be maintained at a temperature of 20 degrees, however most accounts of the water temperature ranged from icy cold to sub-Siberian.

Upon the outbreak of World War 2 the pool was camouflaged so as to appear to be a field from above, preventing it from being used as a marker for enemy bombers targeting the power station next door. The pool reopened on the 1st June 1946 and was as popular as ever, though that may have something to do with Sean Connery working there as a lifeguard during the 1950’s.

It was during this period that the bathing pool hosted numerous galas and diving shows, making visitor figures soar. Many of the posters for these performances can be found in the Museums & Galleries Edinburgh collection. During the 1970’s the pool’s popularity dwindled with the increase of cheap package holidays abroad. A further blow came when the power station closed in 1978, meaning the water could no longer be heated. In 1979 Portobello bathing pool closed its doors for the final time and was demolished in 1988. In its place now stands a five-a-side football pitch and a leisure centre. Meanwhile, memories of the pool live on.

You can find more images of Portobello outdoor bathing pool and other seaside attractions at www.capitalcollections.org.uk

Auld Reekie Retold is a major three-year project which connects objects, stories and people using Museums & Galleries Edinburgh’s collection of over 200,000 objects. Funded by the City of Edinburgh Council and Museums Galleries Scotland, the project brings together temporary Collections Assistants and permanent staff from across our venues. The Auld Reekie Retold team are recording and researching our objects, then showcasing their stories through online engagement with the public. We hope to spark conversations about our amazing collections and their hidden histories, gathering new insights for future exhibitions and events.

-

5min Article

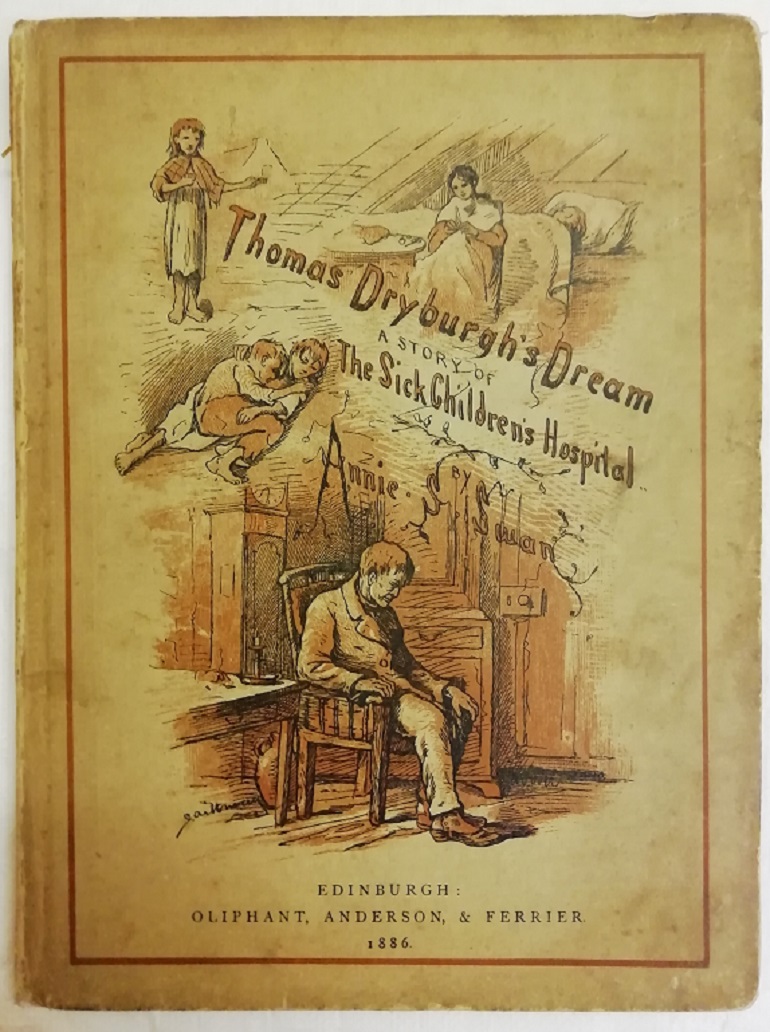

In this blog, Lyn Stevens, curator at the Museum of Childhood explores the origins of a much loved Edinburgh institution, the Royal Hospital for Sick Children which recently moved to a new location.

A little book and a little bear in the Museum of Childhood collection span a history of over 100 years in the story of medical care provided for children in the city of Edinburgh. Edinburgh was one of the first cities in the world to have a hospital dedicated to children and to study the illnesses of childhood as a separate discipline.

Edinburgh’s Royal Hospital for Sick Children, known locally as ‘The Sick Kids’, began life in 1859 as a campaign for a children’s hospital launched by Dr John Smith who published an open letter in ‘The Scotsman’ newspaper. The letter described the suffering of the children amongst the poorest classes - ‘the whisperings of distress lisped out by those unfortunate little creatures are too feeble to attract attention’ read the emotional plea, ‘we must not shut our eyes’ to this situation.

By the following year a children’s hospital in Edinburgh was established in a house in Lauriston Lane with 20 beds. A royal charter was granted in 1863, and after several moves to various locations, the Sick Children’s Hospital was officially opened on 31 October 1895.

The report of the hospital’s first year stated ‘154 children of ages 1 year to 12 years admitted and treated, of whom 140 have been cured and restored to their parents and friends. In the dispensary attached to the hospital 985 children have during the same short period, received medicine – and when necessary they have been visited at their parent’s dwellings and a truly great amount of disease and suffering has thus also been relieved’.

At the time of the hospital being first established the Edinburgh Old Town was a filthy and poverty-stricken slum. There was no sanitation and stinking sewage was everywhere. The death rate of children under 5 was one in 13.

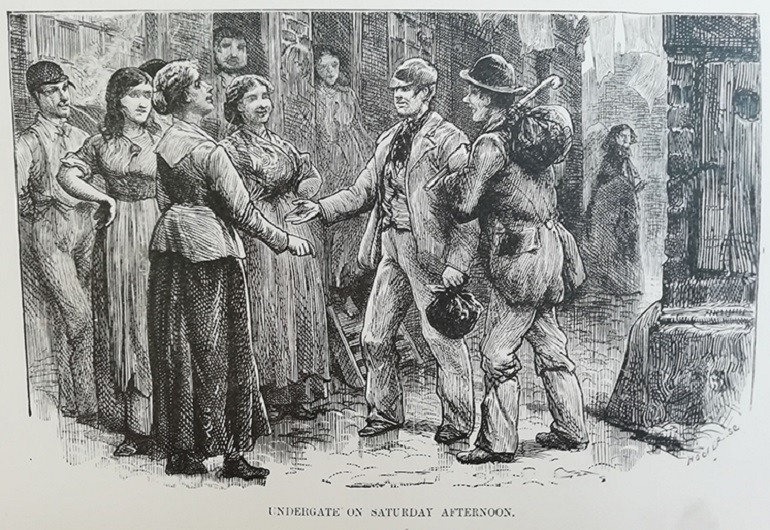

When Annie S Swan’s book ‘Thomas Dryburgh’s Dream A Story of the Sick Children’s Hospital' was published in 1886 the Old Town was still the home of the poorest of the city and the conditions had barely improved. In the book Swan describes the fictional city of Dunleith (Edinburgh) and the poor area of Undergate (Cowgate) where the heroines of the story live. Mary Derrick is a widow with a young daughter trying to earn a living in the big city by sewing. Swan is careful to paint Mary as respectable in her poverty, she hasn’t fallen into prostitution or drink, but she is doing the best she can. However, as her child is sick from malnutrition and damp living conditions, her best is not enough to keep her child healthy.

Mary had come from a picturesque farm in the country where her brother still lived and had moved to the city when she married. Her husband’s death had meant poverty for Mary and her daughter and her brother was unwilling to help as he felt her fate was what she had deserved for going off to get married and leaving him to run the farm on his own. Her brother, Thomas Dryburgh, has a dream where he floats over the city and sees the poverty of the poor children shivering in doorways with bare feet. The dream results in a Dickensian like change of heart (think of Scrooge in ‘A Christmas Carol’), and he comes to the city on Christmas Eve to rescue Mary and donates money to the children’s hospital where his niece is being nursed back to health.

The book ends with a happy scene of the Thomas, Mary and the child back on the farm in healthy surroundings, and a view of Thomas’s bureau, where his will is kept, leaving a legacy for the children’s hospital upon his death. The book is a plea for donations to the children’s hospital.

The author Annie S Swan lived in Morningside in Edinburgh in the 1880s and in addition to the Royal Hospital for Sick Children (Sick Kids) a new Bruntsfield Hospital for women and children had opened the year before Swan’s book was published. The new dispensary for women and children was established by Dr Sophia Jex-Blake, the first woman to practise medicine in Scotland, and one of the ‘Edinburgh Seven’, the first women to be allowed to study medicine at the University of Edinburgh. This hospital was later to amalgamate with the Hospice set up by Elsie Inglis on the High Street, and the two together became the Elsie Inglis Maternity Hospital at Abbeyhill. It is likely Swan would have been aware of all of these efforts to provide better healthcare for the poor children of the city.

Jump ahead over a 100 years and a teddy bear was made to support a 1991 fundraising campaign for a new wing at the Sick Kids hospital. The bear in the collection is named ‘Jamie’ and he was donated by one of the fundraisers for the new wing. The target for the fundraising was £10 million, a figure probably inconceivable to the hospital fundraisers in the nineteenth century. However, this campaign demonstrates that charitable donations to the hospital are not a thing of the past. The campaign was successful, and the new three storey wing was opened in 1995. Still fundraising, the Edinburgh Children’s Hospital Charity supports the work of the hospital to ensure that the children who go there have the best experience possible. The charity is currently running a Covid-19 emergency appeal and continues to fundraise for the Hospital. Read the What we do page on their website.

In 2021 the hospital is about to move into a new £150 million building at a new location at Little France adjoining the Royal Infirmary Hospital. A little bear and a little book illustrate the provision of health care for children from the nineteenth to twentieth centuries, something which has always been supported by the people of Edinburgh.

Auld Reekie Retold is a major three year project which connects objects, stories and people using Museums & Galleries Edinburgh’s collection of over 200,000 objects. Funded by the City of Edinburgh Council and Museums Galleries Scotland, the project brings together temporary Collections Assistants and permanent staff from across our venues. The Auld Reekie Retold team are recording and researching our objects, then showcasing their stories through online engagement with the public. We hope to spark conversations about our amazing collections and their hidden histories, gathering new insights for future exhibitions and events.

Keep an eye on our events page to book your place at our upcoming, free Auld Reekie Retold digital talks and events. You can find out more about Auld Reekie Retold and read more blogs on the Stories section.

You can find out more about Auld Reekie Retold object discoveries from our Museum Collections Centre on the Capital Collections website.

Further reading ; read more about the history of the Royal Hospital for Sick Children on the Our History section of their website

-

Auld Reekie Retold is a major three year project which connects objects, stories and people using Museums & Galleries Edinburgh’s collection of over 200,000 objects. Funded by the City of Edinburgh Council and Museums Galleries Scotland, the project brings together temporary Collections Assistants and permanent staff from across our venues. The Auld Reekie Retold team are recording and researching our objects, then showcasing their stories through online engagement with the public. We hope to spark conversations about our amazing collections and their hidden histories, gathering new insights for future exhibitions and events.

We have already met the Curators and the Collections team. In this blog, we meet Russell Clegg, Collections Engagement Officer. We asked Russell to say a few words about how he got into museums, what he does, what he likes best about his job, and some of his personal interests from the collections.

I recently joined the Auld Reekie Retold team as Collections Engagement Officer following five years as Learning Officer at the Patrick Geddes Centre at Riddle’s Court. Prior to that I worked for Edinburgh Museums and Galleries in an exhibitions and outreach role.

I studied History at University and I like to uncover connections between things, places and people. I really enjoy engaging folk around social history themes particularly but also using objects as portals into the past, from which we can learn about culture and society. I also like tours and trails, especially if they lead to intriguing buildings or spaces!

I love objects which involve rituals. In 2014, I curated an exhibition based essentially on ‘going out’ and came across the strangest sporran in the collections store. Instead of tassels it had what looked like animal hair tresses but platinum blonde! It fascinated me because someone, maybe even several owners, obviously loved it once and it made me wonder about them. A lack of detail around its provenance generated lots of questions: when and where was it worn, was it a bespoke creation and what was kept inside it? Sadly, exhibiting the sporran did not yield any further information and it is now back in its box, deep in our Museum Collections Centre store!

My role on Auld Reekie Retold is to bring the discoveries, research and stories uncovered by my curatorial colleagues to the public. Under normal circumstances, this would involve organising and facilitating face-to-face events such as tours, talks and workshops. However, as my job began during the public heath restrictions around the Covid-19 pandemic, I am currently curating online events and social media posts and happenings around Auld Reekie Retold. This includes a series of digital public talks which have delved further into the objects in our care, shining a light on why we have them and how they relate to Edinburgh’s past. One such event was a presentation with colleagues on the theme of ‘Together whilst Apart’. This involved looking at a specific collection of personal objects and keepsakes related to the idea of how folk have historically dealt with separation from each other. I am also in discussion with organisations, such as local history societies and community groups, around the city to understand what links they might have to the objects we are discovering in our stores and how we can record stories and information around them to build on and extend our existing knowledge.

In the coming months, when we can gather and meet again, I will be seeking to link communities of local interest to our collections. We want to add a dimension of ‘lived experience’ around our holdings especially those not on display in our museum venues. Catching stories and reminiscences about artefacts we own will mean that future audiences have greater context and real empathy about how our material culture was created, used, worn and loved before we came to look after it.

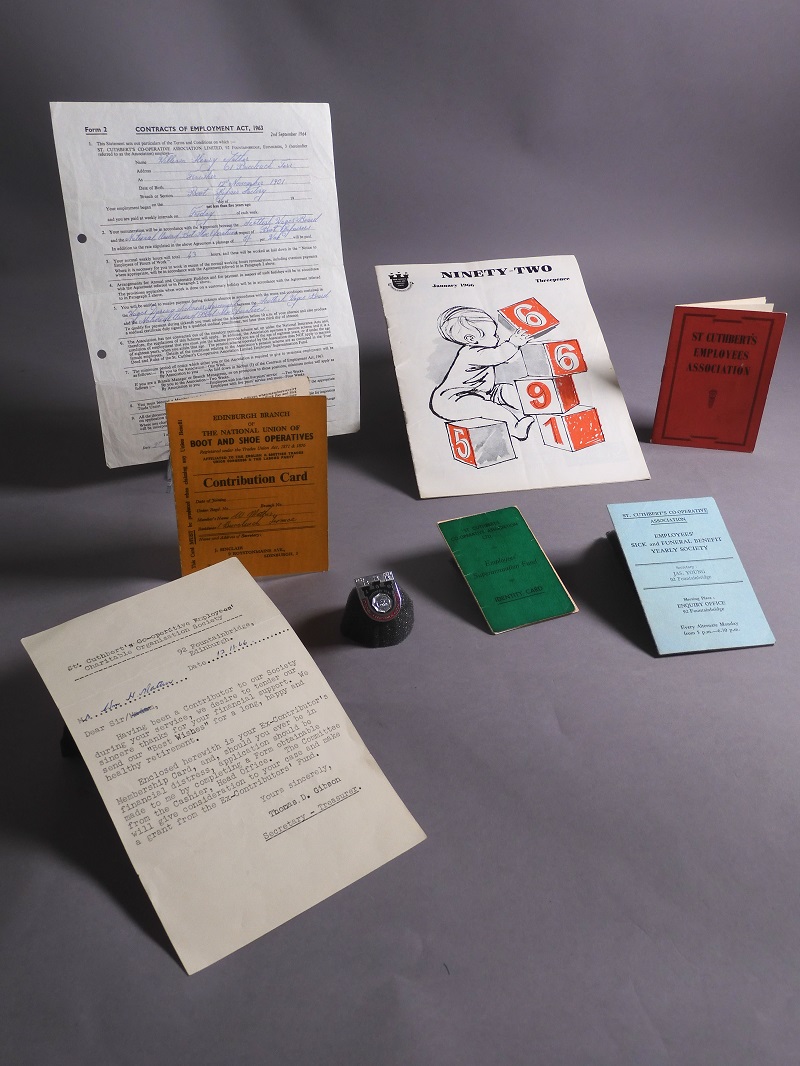

Coming to live in Edinburgh from Rochdale, the home of the original model of Co-operative Societies, I am keen to hear from Edinburgh folk who worked for the St. Cuthbert’s Association or Leith Provident in the mid- 20th century, to bring the collections we have about this fantastic movement right up to date!

Keep an eye on our events page to book your place at our upcoming, free Auld Reekie Retold digital talks and events. You can find out more about Auld Reekie Retold and read more blogs at www.edinburghmuseums.org.uk/auld-reekie-retold.

You can find out more about Auld Reekie Retold object discoveries from our Museum Collections Centre on the Capital Collections website.

-

Auld Reekie Retold is a major three year project which connects objects, stories and people using Museums & Galleries Edinburgh’s collection of over 200,000 objects. Funded by the City of Edinburgh Council and Museums Galleries Scotland, the project brings together temporary Collections Assistants and permanent staff from across our venues. The Auld Reekie Retold team are recording and researching our objects, then showcasing their stories through online engagement with the public. We hope to spark conversations about our amazing collections and their hidden histories, gathering new insights for future exhibitions and events.

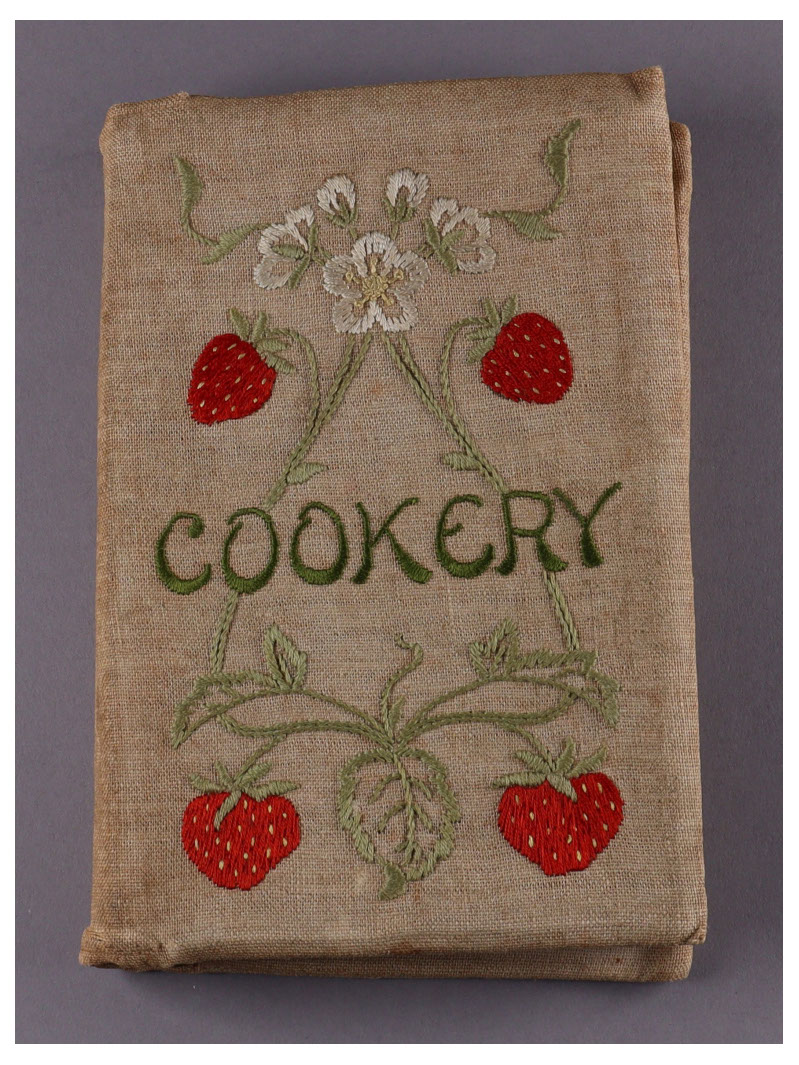

In this blog, history curator Vicky Garrington explores the story of the Edinburgh College of Domestic Science, affectionately known as ‘Atholl Crescent’.

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh recently released the first film in a series called Cooking Up the Past. Collections Assistant Oliver Taylor and I found a recipe from a book in our stored collections and tried recreating it at home during the pandemic restrictions. We made soda scones from the book Plain Cookery Recipes, produced by the Edinburgh College of Domestic Science in 1932.

The college principal, P.L. Wingfield, notes in the preface of Plain Cookery Recipes that the recipes in the book are not only relevant to students, but ‘…should be of value to every housewife…the dishes will provide simple, nourishing food’. This reference to an audience beyond the College and the need to create nourishing food hints at the College’s ground-breaking founding principles.

The College began life as the Edinburgh School of Cookery and Domestic Economy in 1875. Its founders, Christian Guthrie Wright and Louisa Stevenson, were heavily involved in furthering the education of women. In founding the college, they had two aims: to improve women’s access to higher education and to improve the diets of working class families. They began to hold lectures at the Royal Museum (now the National Museum of Scotland), as well as arranging lectures and demonstrations across the country.

In 1891, the School moved to Atholl Crescent in Edinburgh’s West End, where its main campus remained until 1970. It became the Edinburgh College of Domestic Science in 1930, but to many in the City it will always be ‘Atholl Crescent’. Many developments followed, including a broader curriculum, and the institution eventually became Queen Margaret’s University.

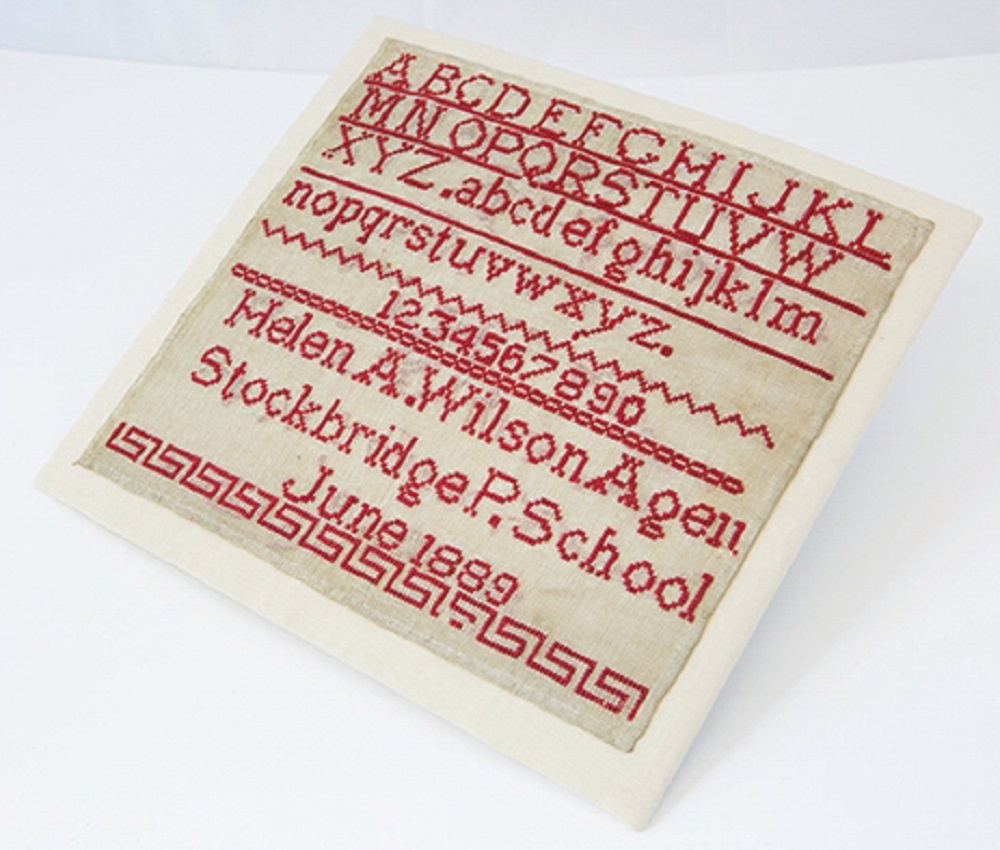

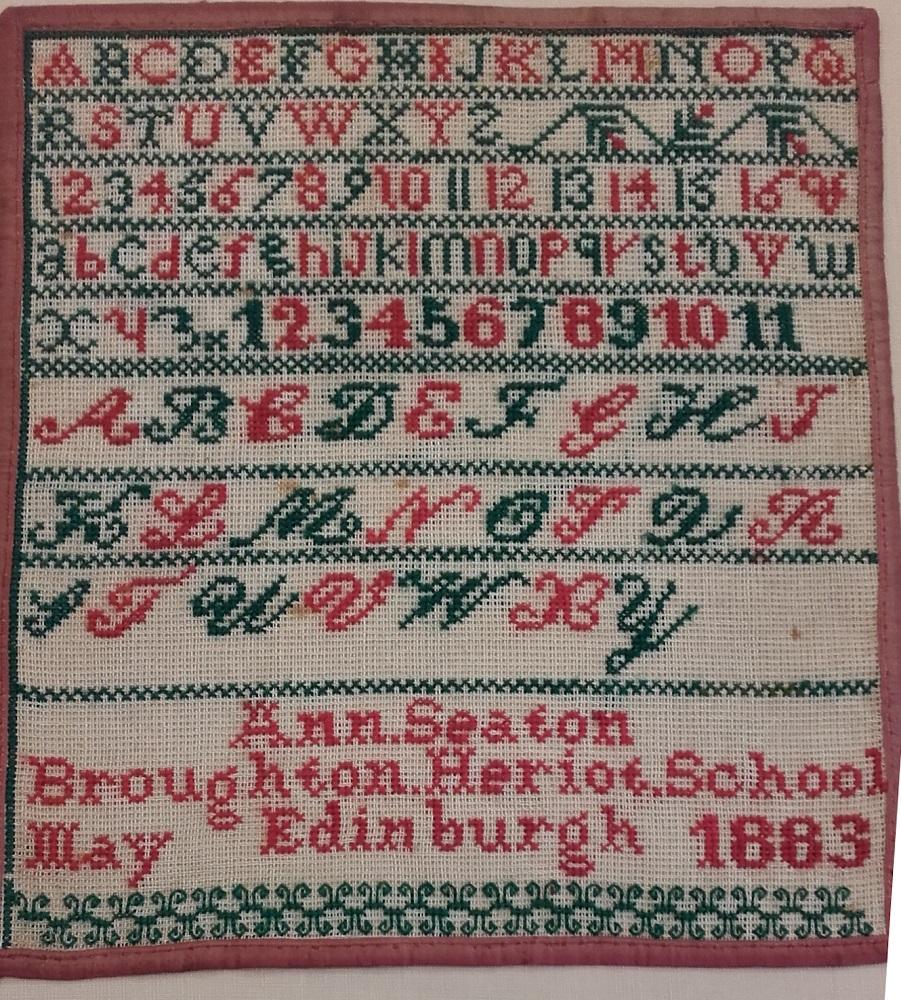

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh holds a collection of objects relating to the Edinburgh College of Domestic Science. It includes text books and samples of work completed by students of needlework courses. Many of the needlework pieces we hold were completed by Maud Pentland (later Maud Steven). Maud was born in 1895 and studied Needlework Design at Atholl Crescent from 1914 to 1916. She studied under Louisa M Chart, who also taught at the Edinburgh College of Art. Maud’s samples of embroidered blouses, skirt seams, millinery embellishments and other pieces show her consummate skill, and it is easy to see why she was awarded a number of prizes for work exhibited at the Edinburgh College of Art. In 1921, Maud was offered a place as Assistant Sewing Mistress at Edinburgh Ladies College (later the Mary Erskine School). She also taught at other schools around Edinburgh and at night classes.

Maud was at Atholl Crescent at an exciting time. In the early 20th century, the school leadership were acutely aware of the damaging effects of childhood malnutrition. The child mortality rates for the working classes were shockingly high, and the teaching of domestic science in schools was seen as key to reducing them. Government listened, and domestic science became part of the curriculum in schools.

The history of the Edinburgh College of Domestic Science illustrates the fight for women’s education, an end to child malnutrition and the formalisation of ‘home’ skills that was raging at the turn of the twentieth century. It shows how publishing a recipe book can be a radical act, and gives us food for thought as we enjoy our scones.

You can view episode 1 of Cooking Up the Past on YouTube.

You can find the recipe for soda scones from the book Plain Cookery Recipes here.

You can see more Auld Reekie Retold project objects online at www.capitalcollections.org.uk.

-

Cooking Up the Past 1: Soda Scones from Atholl Crescent

Join Vicky and Oliver from the Auld Reekie Retold project team at Museums & Galleries Edinburgh as they attempt to make soda scones from a 1932 recipe book while exploring the history of the Edinburgh College of Domestic Science, known locally as ‘Atholl Crescent’.

This video was made during Covid pandemic restrictions, so most scenes are filmed at home using phone cameras. We hope any minor quality issues don’t spoil your enjoyment.

We’d love to see your attempts at baking from historic recipe books – you can tag us on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram using the hashtag #AuldReekieRetold

Bake along with us! Here is the recipe for the soda scones:

½ pound (225g) of plain flour

½ tsp of bicarbonate of soda

½ tsp of cream of tartar

½ tsp of salt

1 gill (118 mil) of buttermilk

Method:

Sieve dry ingredients into a large mixing bowl. Add enough buttermilk to form a soft dough.

Knead the dough lightly on a floured board/ surface. Roll to ½ inch (roughly 1.5 cm).

Cut into four pieces. Warm a griddle or heavy-bottomed pan. Add scones and cook until risen and light brown underneath. Turn and cook until dry in the centre.

No serving suggestions are provided in the recipe, but we enjoyed our scones buttered, and even cut in half and fried, together with some crispy bacon or an egg!

Auld Reekie Retold is a major three year project funded by the City of Edinburgh Council and Museums Galleries Scotland. We aim to connect objects, stories and people using Museums & Galleries Edinburgh’s collection of over 200,000 objects. You can find out more about the project, plus access blogs, event booking information, podcasts and more here.

Cooking Up the Past 1: Soda Scones from Atholl Crescent

-

To celebrate International Women’s Day 2021 and Women’s History Month our curatorial and collection team profiled five pioneering women whose lives are reflected by our collections. The series forms part of our current Auld Reekie Retold project, an extensive and ambitious project connecting Edinburgh’s people to its collections. Each historic woman was nominated by one of our female colleagues and all the featured objects or photographs are currently held in our social history, childhood or applied art holdings.

Ella Morrison Millar – chosen by History Curator, Victoria Garrington

Ella Morrison Millar (1869-1959) was Edinburgh’s first female Town Councillor. Elected in 1919, she campaigned against poverty and for better education and housing. She served until 1949 and, following her retirement, was known as the ‘Mother of the Council’ for her service. Her name lives on in the Morrison Millar women’s golf tournament, which she established in 1928. Museums & Galleries Edinburgh have a pair of her shoes in their dress history collection. They are gold leather heels, bought from the well-known Edinburgh store Darling’s in the 1930s. The shoes were recently featured in the exhibition ‘Stepping Out’ at the Museum of Edinburgh.

Nannie Brown – chosen by History Curator, Anna MacQuarrie

Nannie (Agnes Henderson) Brown (1866 -1943), was a prominent Edinburgh-born suffragist. In 1912, she was one of only six women who participated in the ‘Brown Women’ walk from Edinburgh to London, in support of women’s suffrage. Each of the women wore brown overcoats on their walk, hence their collective name. Prior to 2018, we had only one object in our collection connected to her - this studio portrait with a medal clearly seen on her lapel. In 2018 a small collection of objects belonging to Nannie and her sister, Jessie, were donated to Museums and Galleries Edinburgh. The medal, pictured was one of these objects, awarded for her contribution to the 400-mile walk. It is inscribed on the reverse with her initials, N. B. and the date it was awarded to her. The other objects donated include notebooks filled with recipes, craft instructions and observations from the sisters’ excursions to continental Europe. These important objects allow us to expand our research on these interesting women and the lives they led.

Lileen Hardy - chosen by Museum of Childhood Curator, Lyn Stevens

Lileen Hardy (1872-1947) opened the St. Saviour’s Child Garden in 1906 in the Canongate, part of Edinburgh’s Old Town, as the second free nursery provided for the poor children in Edinburgh. Hardy was part of a network of social reformers within the city including Elsie Inglis, Patrick and Anna Geddes and Canon Laurie of Old St. Paul’s Church. Their shared ambition was to foster opportunities for children in the urban slums to enjoy green space, time to learn and access to nature, not seen as beneficial at the time. Many of the younger children in the Old Town were left to entertain themselves while their parents worked or were incapacitated. Hardy needed help and funds for her Kindergarten and sought to raise awareness by producing a booklet entitled The Life History of a Slum Child outlining the dangers on the streets and homes presented to these children. The Museum of Childhood displays a copy of this booklet as part of its collection reflecting the pioneering work of Lileen Hardy.

Helen Monro Turner – chosen by Applied Art Curator, Helen Edwards

Helen Monro Turner (1901-1977) founded the studio glass department at Edinburgh College of Art, where she taught glass engraving and was head of department for 30 years. Monro Turner studied glassmaking in Stuttgart in the late 1930s, then set up her own studio in Edinburgh. The photo shows her at work in her studio at Juniper Green. Museums Galleries Edinburgh have her treadle powered engraving lathe and her cabinet of copper engraving wheels in our collections. The lathe was formerly used at the Holyrood Glassworks, which closed in 1904. Descendants of the Ford family, former owners of the glassworks, gifted it to Monro Turner for her use. The engraved glass with the ‘pigeons’ motif is an example of her work in our collections and a symbolic link between the glassworks, and an artist and educator who passed her skills on to future generations.

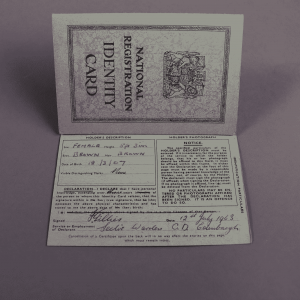

Ena Thomson – chosen by Collections Care Officer, Gwen Thomas

Ena Thomson (1907-1989) served as an Air Raid Warden in Edinburgh’s Air Raid Precaution corps, or ARP during WWII. She joined at a time which saw many women enter the workforce, becoming factory workers, drivers and medics. ARP Wardens enforced the blackout, gave out gas masks and instructed the public in emergency safety actions. Some were even stationed on the roof of Jenners as lookouts for enemy bombers, ready to sound the air raid sirens. Thomson joined the ARP in June 1939, several months before the war officially started. Objects we have relating to her service, include her insignia and her book of Warden report forms, used for reporting bomb strikes, including the location, type of bomb, damage, and casualties. After the war, she joined the Civil Defence Corps, set up to act as a safeguard in case of a nuclear attack. She was a volunteer until it was disbanded in 1968, when she received a long service medal for her almost 30 years of public service.

-

Marking International Women’s Day 2021 curators from Museums & Galleries Edinburgh have taken the opportunity to shine a spotlight on a selection of fascinating women from Edinburgh’s past.

Running from 8th – 12th March the series profiles five pioneering women whose lives are reflected in the city’s history collections. They include; Ella Morrison Millar (1869-1959) Edinburgh’s first female Town Councillor chosen by chosen by History Curator, Victoria Garrington, Nannie (Agnes Henderson) Brown (1866 -1943), a prominent Edinburgh-born suffragist chosen by History Curator, Anna MacQuarrie, Lileen Hardy (1872-1947) who opened the St. Saviour’s Child Garden in 1906 in the Canongate chosen by Museum of Childhood Curator, Lyn Stevens, Helen Monro Turner (1901-1977) who founded the studio glass department at Edinburgh College of Art chosen by Applied Art Curator, Helen Edwards and Ena Thomson (1907-1989) who served as an Air Raid Warden in Edinburgh’s Air Raid Precaution corps, or ARP during WWII chosen by Collections Care Officer, Gwen Thomas.

The story of each woman is explored and showcased using linked objects from the collection which include: a studio portrait of Nannie Brown, a pair of Ella Morrison Miller’s gold leather shows purchased from Edinburgh’s well-known department store Darlings in the 1930’s and WWII ARP identification papers for Ena Thomson. These objects and many others have been unearthed as part of the ongoing Auld Reekie Retold inventory project which is working to connect Edinburgh’s people to its collections.

From the 8th March, the curators will reveal full details of each women’s story alongside the items from the collection which connects their own unique history, providing compelling insight into our city’s history from just a few of the women who helped shape the Edinburgh we know today.

The series which is introduced by Councillor Amy McNeese-Mechan, Vice Convenor of Culture & Communities will be shared online via the Museums & Galleries Edinburgh website and social media channels from 8th-12th March.

Commenting on the series, Councillor McNeese-Mechan said: ‘It is fascinating to learn about how our collections both preserve and mirror the work of women in Edinburgh’s civic and cultural life. This series shines a light on five women who made significant contributions to our city’s history but who sadly are far from well known.

I hope the stories of these wonderful women will inspire you and I look forward to more discoveries from the Auld Reekie Retold project.”

Helen Edwards, Applied Art Curator with Museums & Galleries Edinburgh said: “Working on the Auld Reekie Retold project has given us the opportunity to research some of the hidden histories behind our collections. It’s been fascinating looking into some of the stories of the pioneering women from Edinburgh, and International Women’s day is a real chance to get their stories out to a wider audience and let their voices be heard.”

The series is accompanied by a fascinating programme of free digital lectures and family events including; Scots Women who Chose to Challenge with Jackie Sangster is a Learning Manager at Historic Environment Scotland, Aunts: In Fact & Fiction with Ruthanne Baxter, Museums Manager and Prescribe Culture Lead at the University of Edinburgh, An (Almost) A to Z of Modern Scottish Women Artists with Alice Strang, Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the National Galleries of Scotland. Look Outside, a family craft event inspired by the work of artist Kate Downie and Votes for Women - The Keystone to Liberty, a digital performance from Edinburgh Living History. For full details and bookings click here.

-

Auld Reekie Retold is a major three year project which connects objects, stories and people using Museums & Galleries Edinburgh’s collection of over 200,000 objects. Funded by the City of Edinburgh Council and Museums Galleries Scotland, the project brings together temporary Collections Assistants and permanent staff from across our venues. The Auld Reekie Retold team are recording and researching our objects, then showcasing their stories through online engagement with the public. We hope to spark conversations about our amazing collections and their hidden histories, gathering new insights for future exhibitions and events.

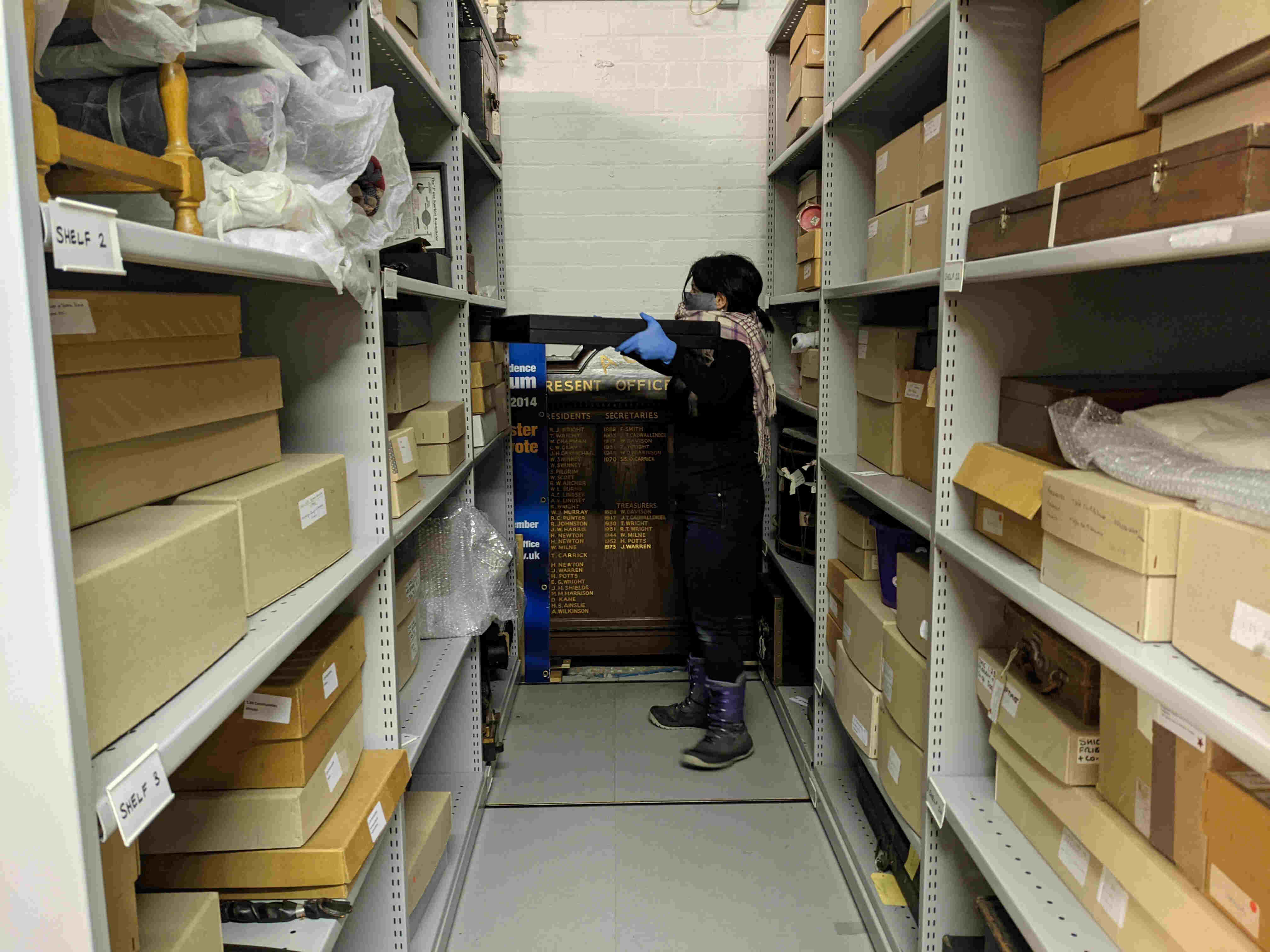

In this blog, Gwen Thomas, Collections Care Officer gives an insight into what goes on in our collections stores and why we store things.

Why do we have objects in store?

The main reason we have objects in store is that we have too many objects to display at once in our museum and gallery venues. When an object can’t be displayed, it is best looked after in a museum store. In the store, we are able to manage the factors which can cause damage: dust, light, handling, incorrect temperature and relative humidity, and of course security problems. The Museum Collections Centre in Broughton is our main store, but we keep parts of the City’s collection in other stores across Edinburgh too. Objects in store can be packed together a lot more tightly in store than they would be on display, whilst still remaining accessible.