Built in the 1590’s with substantial additions dating from 1820’s, Lauriston was not founded on the profits of slavery or colonialism, but there are connections to slavery and colonialism within its history of ownership and within some of its collections. This blog looks at some of Lauriston’s past owners.

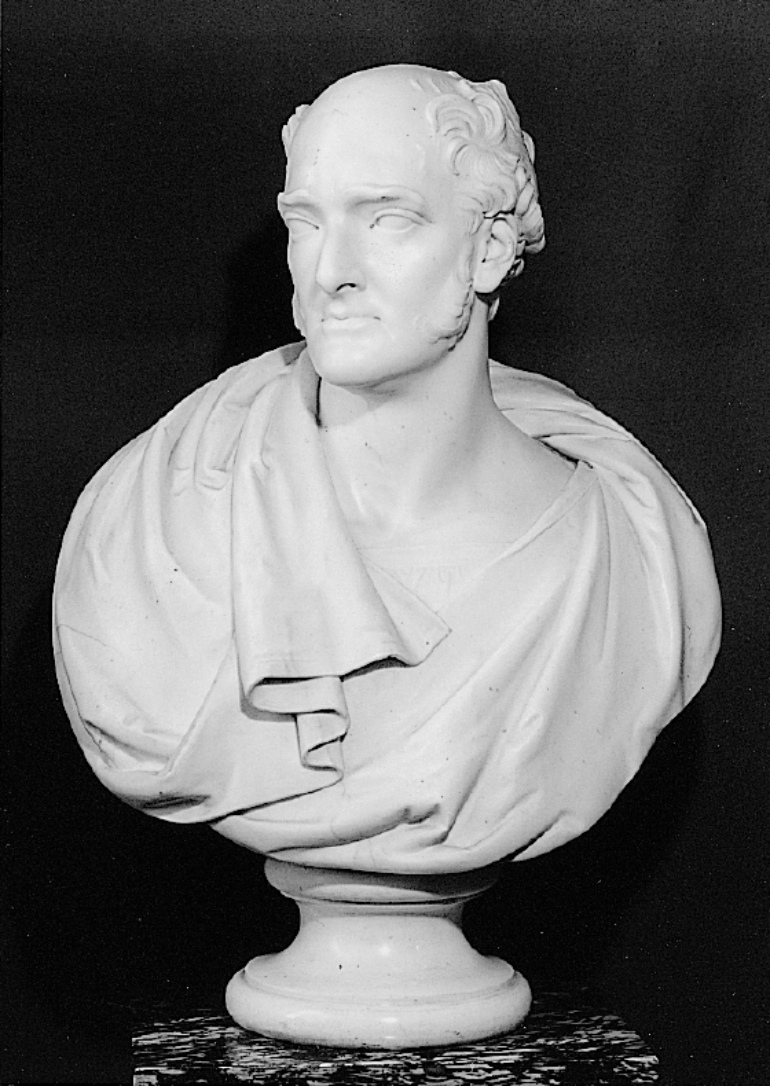

John Law

John Law was one of Lauriston’s most controversial owners. He was a brilliant mathematician and was also a gambler, but having killed a man in a duel, he was imprisoned. He escaped to France where his mathematical and financial skills led to him becoming Controller General of the Finances of France. Law, along with the Duc d’Orleans, established the Company of the West to develop French colonies in Louisiana – also known as the Mississippi Scheme. The Royal Bank of France, which Law established with the Duc d’Orleans, had exclusive trading rights in the East Indies, China and the South Seas.

John Law’s father, William Law, a wealthy Edinburgh Goldsmith, had died in 1684 having purchased Lauriston in 1683. Although he may have intended to live in Lauriston, his illness and death so soon after the purchase of the castle means that the Law family are unlikely ever to have lived there, instead remaining in their town house within the city.

John, as his eldest son, inherited Lauriston but sold his interest in it to his mother to pay his gambling debts in 1693. He inherited Lauriston for a second time in 1707 following the death of his mother, but was only able to return to Britain in 1721 after a Royal pardon had been issued for his part in the death of Edward Wilson in the duel that they had fought some 27 years earlier. It is unlikely that Law ever returned to Lauriston or to Scotland.

But although John Law has no direct connection with Scottish or British Colonialism, as France’s most influential financier of the early 18th century, though the development of French Colonies in Louisiana and through the National Bank’s monopoly on trade in the East Indies and China, he was certainly an instrumental figure in French colonial history and is a figure who has a strong family link to Lauriston Castle.

Margaret Gordon MacPherson Grant

A much more direct link between one of Lauriston’s past owners and wealth created through the proceeds of colonialism came in 1859 when Margaret Gordon McPherson Grant of Aberlour purchased Lauriston Castle for her father.

Rachel Land of University College London has researched Margaret Gordon MacPherson Grant and her family’s links to slave derived wealth.

Margaret Gordon MacPherson Grant was born on April 27th, 1834 in Aberlour, Banffshire. She was the second child of Alexander MacPherson, a physician, and his wife, Annie Grant MacPherson. Her older brother Alexander died in India in 1852 leaving Margaret heir to her uncle’s fortune. Alexander Grant had amassed a considerable fortune through his ownership of slave plantations in Jamaica. He also traded as a merchant and was a member of the Jamaican Legislature, only returning to Britain in the 1820s. When slavery was abolished in 1833, he profited from the British government’s compensation scheme for his lost ‘property’ – his slaves and other business assets – for which he was given £24,000, which now would be the equivalent of over £2 ¾ million. Aberlour house was built on the profits of his plantations and the compensation he received as a slave owner. He probably never lived there as he preferred to live in London, where he maintained his business as a successful merchant in the West Indies until his death in 1854.

Alexander Grant had made his niece his sole heir on the proviso she changed her name to Grant and so Margaret Gordon MacPherson Grant, at the age of twenty, inherited the bulk of his wealth, along with Aberlour house and his estates in Scotland and Jamaica valued at a total of £300,000. This was a huge sum, the equivalent of nearly £36 million today. He also left her an outright settlement of £20,500 payable at his death and an annuity of £1,500.

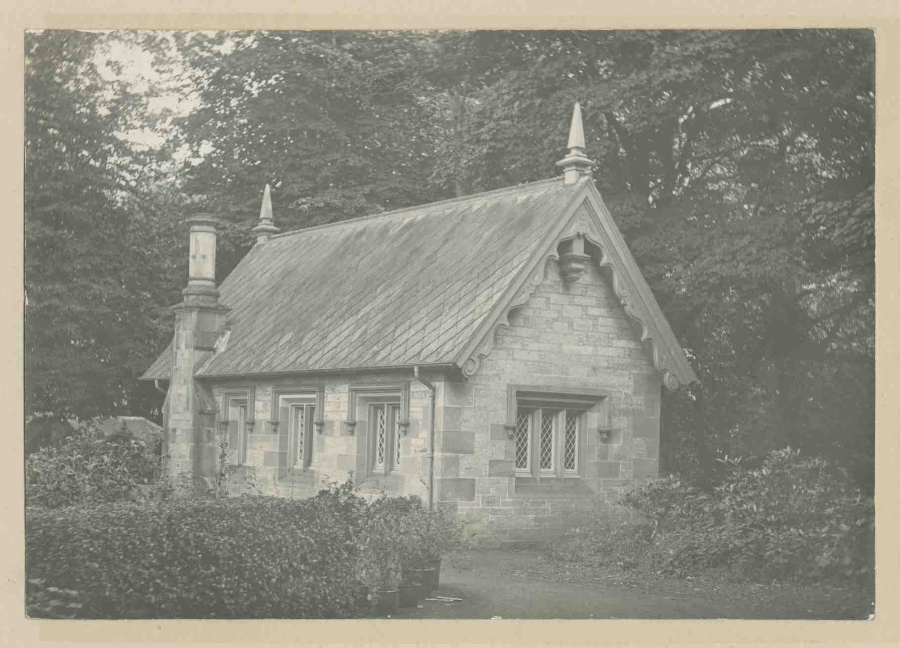

Margaret moved into Aberlour House and immediately started improving and extending the building adding bay windows and a ballroom. Her agents, Milne & Co in Elgin managed her Jamaican estates. Aberlour House was the main residence for Margaret and her parents, but after the death of her mother in 1858 she purchased Lauriston from Charles Halkett Cragie Inglis in May 1859 for £8,875. Although it was Margaret who purchased the castle, it was her father who mainly lived there as Margaret spent much of her time at Aberlour House or in London. But Margaret did spend some of her time at Lauriston with her father, and the 1861 census lists her as a resident rather than a visitor, along with her father and 12 live-in servants. Margaret was interested in cattle breeding and dairy work and it is believed that the building which now houses the public toilets was built as a model dairy. This is the only tangible evidence of her time at Lauriston as the castle was sold to Thomas Macknight Crawfurd for £11,400 in 1871. It has also been suggested that the wall fabric on the walls in one of the tower rooms may date from this period of ownership, though it more probably dates from the 1870s.

Thomas Allen

There seem to be no other obvious colonial connections with other former owners. Although it has been interesting to read some of the Caledonian Mercury reports from the period running up to the abolition of slavery. Thomas Allen, who owned Lauriston in the 1820s was the owner of the ‘Caledonian Mercury’ newspaper. The newspaper largely reports on the debates around the subject of abolition without additional comment so you cannot necessarily infer that the newspaper or its owners had a particular standpoint on the issues discussed. It included ones from the ‘Edinburgh Society for the Mitigation and Ultimate Abolition of Negro Slavery’. The society, as its name would suggest, was for gradual abolition of slavery. There were some dissenting voices at the meetings advocating more immediate emancipation, but the overall focus was to advocate gradual abolition, amelioration of conditions for slaves and compensation for plantation owners. It may simply be that newspapers of this period reported directly and did not add their own opinions, so the opinions expressed within the Caledonian Mercury may not be Thomas Allen’s own, but it can also be argued that failing to take a stance can also result in giving reported opinions tacit approval and perhaps Allan also agreed with this view, or at least did not want to be seen to go against wider public opinion held in Edinburgh at this time.