The week of 3rd June 2024 is Volunteers Week, a time we come together to recognise and celebrate the enormous contribution our army of volunteers make to our museums, galleries and collections. In this blog, Collections Volunteer Alasdair explores some of the Museum Collections Centre's 17th century items.

As a Volunteer Collections Assistant, I literally get hands on with history. Over the last few months, I have been lucky enough to work with the incredible collection in of 17th century objects in Museums and Galleries Edinburgh’s care. These objects can provide a glimpse into the past: from a writer running out of ink on their quill midway through a word, to the marks on a sword blade showing use in the past.

At the cutting edge

Recently I have worked with a series of swords and sword parts from the 17th century. Warfare was a particularly brutal business in this period. Battles were predominantly fought with musket, pike, and artillery, however when in close quarters, swords and other side arms were used. The swords in the collection are called Mortuary Hilts, one was reportedly used during the Battle of Dunbar in 1650. The name is often attributed to the decoration, which often but not always shows a stylised head. This design apparently depicts the severed head of Charles I after his execution in 1649. However, this is unlikely as the design was used by all sides - it was Oliver Cromwell’s sword type of choice - even prior to Charles’ death! It is likely that the name comes from after the conflict when many swords were painted black and incorporated in church funerary displays.

Of the four hilts, three are made of brass, while one is steel. The brass hilts may be indicative of the class of their previous owners, or indeed, an unscrupulous merchant; brass is not a good material for a sword guard due to its brittle nature when struck.

History on a page

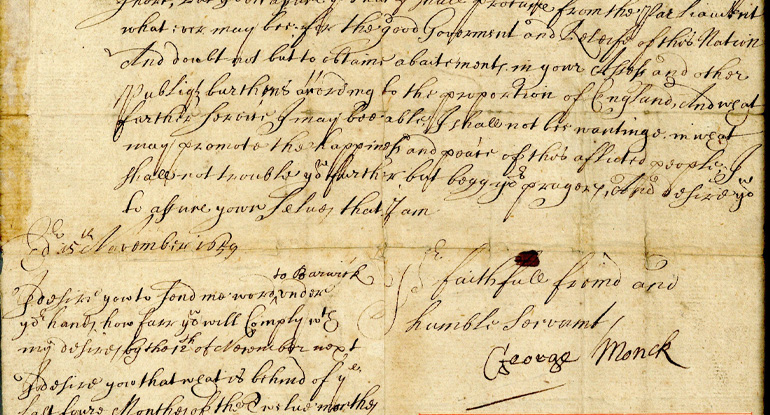

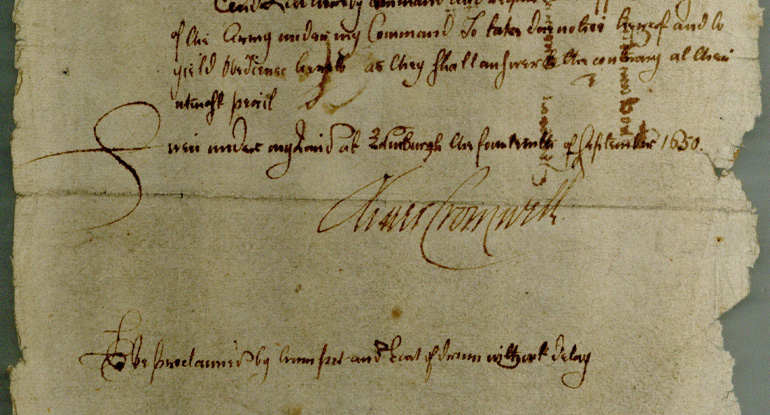

The collection also boasts a series of documents and letters of the period. The documents are historically important and contain a who’s who of the 17th century. The names include Oliver Cromwell, James VII and John Graham of Claverhouse (also known as Bloody Clavers or Bonnie Dundee) to name a few.

One letter, written by George Monck on the 5th of November 1659, to the clerks of the Burgh of Culross. In the letter he warns the town not to associate or correspond with Charles Stuart (Charles II) or his associates, to preserve the parliament led Commonwealth. He also authorised the officials to suppress assemblies and send agitators to the nearest garrison. He then demanded that the clerks send him word on how far they would comply with his desires a week later. This may have been an attempt by Monck to shore up his political position. Within a few short weeks he was instrumental in the restoration of the monarchy, by ordering towns like Culross to not communicate with the exiled monarch he made sure that he was at the centre of negotiations when it came to reinstating Charles II.