Ruksar Hussain has recently completed a Crankstart Internship with Museums & Galleries Edinburgh. In this blog, Ruksar explores the history of Fairy Stories in Scotland from Medieval times to the present day.

When J.M. Barrie came up with the much-loved characters Peter Pan and Tinkerbell, like many Scottish writers he was drawing upon a rich history of fairies and fairy tales. Known by various names, including ‘elves’, ‘fauns’, the ‘fair-folk’, and the ‘good people’, we have almost a millennium of recorded history about these creatures – how much of it do you know?

Medieval Fairy Belief

True Thomas lay on Huntlie Bank,

A ferlie he spied wi' his eye

And there he saw a lady bright,

Come riding down by Eildon Tree.

Her shirt was o the grass-green silk,

Her mantle o the velvet fyne

At ilka tett of her horse's mane

Hang fifty siller bells and nine.

True Thomas, he pulld aff his cap,

And louted low down to his knee

"All hail, thou mighty Queen of Heaven!

For thy peer on earth I never did see."

"O no, O no, Thomas," she said,

"That name does not belang to me;

I am but the queen of fair Elfland,

That am hither come to visit thee."[1]

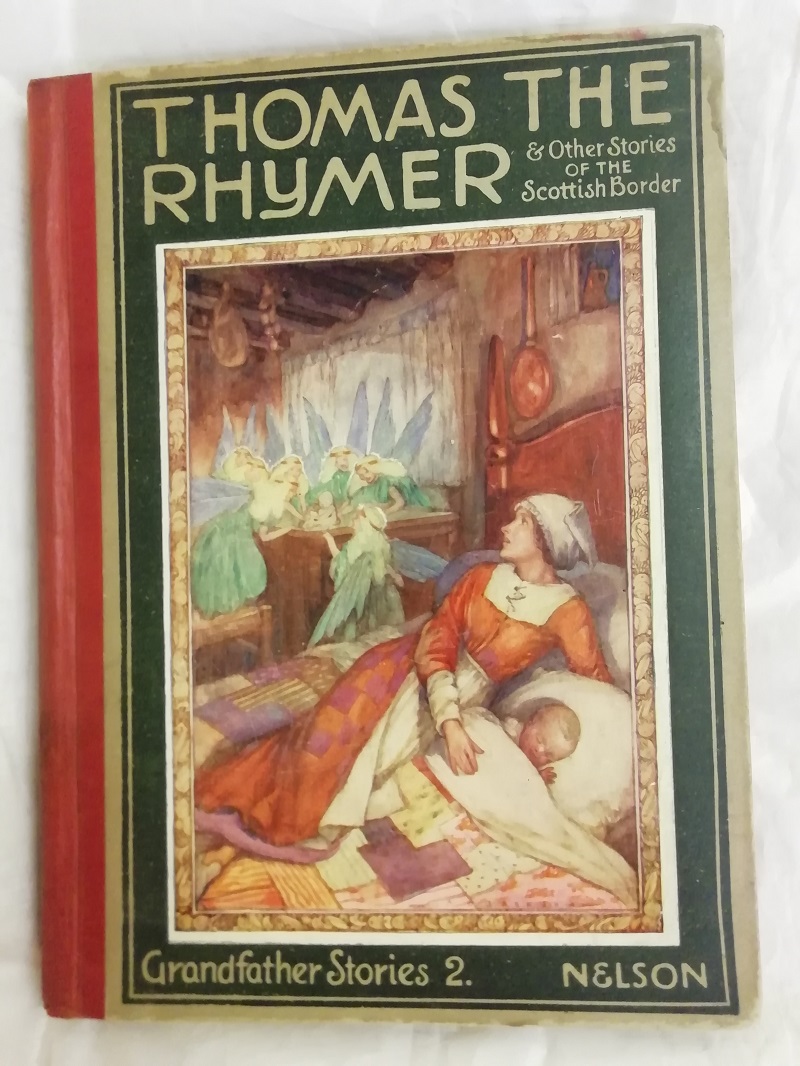

This poem from the 13th century called Thomas the Rhymer, and others you might know like ‘Tam Lin’ or ‘The Elfen Knight’, are our earliest sources that mention fairies. [2] Most medieval Scotsmen would be confused if you asked them if they believe in fairies – the “fair folk” are our “gude neighbours”, they surely do exist! [3] And not just fairies, all sorts of creatures and spirits were believed to roam alongside humans. It was an enchanted universe, where the line between religion and magic was often blurred. These beliefs provided explanation, meaning and mechanisms to cope with what could be a very harsh and frightening world.

What were fairies and Fairyland like?

In the past fairies were understood as potentially extremely dangerous. They could inflict death upon livestock and even people by shooting an “elfshot” or a “blast”. In one source, a woman named Jonet Boyman mentions that her neighbour Allan Andarson and his wife had lost their child to the fairies: “the ‘sillyie wychs’, or seelie witchts, had found it [the child] unsainted and had given it the blast and so it was taken away.”[4]

Paradoxically, it is for this reason that the fairies were referred to with such pleasant names, including the Gaelic Daoine Sith meaning ‘people of peace’. The fairies commanded respect, and giving them sweet-sounding names could help humans avoid offending them.

True, some fairies could be friendly, like the Dame of the Fine Green Kirtle from the Highlands.[5] These fairies belonged to the ‘Seelie Court’ (‘seilie’ being the Scots word for ‘happy’ or ‘lucky’). More malevolent fairies were from the ‘Unseelie Court’, and these attacked humans without reason. In the Thomas the Rhymer poem above we are told that the fairy queen shows Thomas three paths: one to heaven, one to hell, and one to “fair Elfland”. So fairies were not associated with either God or the Devil – not yet, at least.

Sources describe Fairyland as a place of beauty. In the ballads, it was a lush place filled with greenery and music, and the fairies wore fine clothes. The fairy queen’s court was a hall “Whare the roof was o the beaten gold/ And the floor was o the cristal a’”. It was full of wealth and bathed in light, even in the dark hours of the night.[6]

1500-1700: The Reformation, Witch Trials, and the Demonization of Fairies

From about the mid-16th century, there was a change as folk beliefs across Europe came under attack. In places like Switzerland and France, werewolves, which were previously believed to be protectors of their communities, became evil predators that killed livestock and children.[7] In Scotland, fairy belief was the target.

How did the witch-craze begin in Scotland?

Witchcraft became a statutory crime in 1563, but witch-hunting was not new, although it increased. Historians debate the reasons, but most agree that the Reformation was one. Early Protestants had criticised the medieval Church as superstitious, so popular religion and folk belief came under scrutiny.

Since rulers claimed their authority from God, it was a duty to persecute evil and to ensure that their subjects were following the ‘correct’ religious practices and beliefs. Some historians suggest that this anxiety about the ‘godly state’ was particularly strong in Scotland, which became Calvinist by 1560.[8]

Then there’s also the personal role of James VI. It was James who set off the first wave of witch trials in 1590, when he believed his stormy voyage from Denmark back to Scotland had been bewitched.[9] Witchcraft threatened not only the spiritual wellness of his country, but his own life and authority as king. After personally presiding over the North Berwick trials of 1590, he later wrote a book about witchcraft in general called the Daemonologie.

What do the witch trials tell us about fairy belief?

The first record of fairies and witches comes from the trial of Bessie Dunlop, an Ayrshire woman who was convicted in 1576 and burned, probably on Castle Hill. Bessie was a healer who derived her power from the fairies. She claimed that the dead Thome Reid, who had actually gone to live with them, had first introduced her to the fairy queen.[10]

The 1588 trial record of Alison Pearson indicates she was burned for “hanting and repairing with the gude nychtbouris and Quene of Elfame” (haunting and communing with the ‘good neighbours’ and Queen of Elfland). She too had been introduced by a dead man living with the fairies, her uncle, William Sampson. Pearson claimed that the fairies had hit her for revealing their secrets, and the mark she bore was insensitive to pain, which was taken as proof by the authorities of her pact with the devil. [11]

In 1618, John Stewart confessed that he’d met the fairy king in Ireland 26 years earlier on Halloween and again 3 years later. The king had given him powers, and he met with them on Saturdays at Lanark Hill or Kilmaurs Hill in Ayrshire. Like Pearson, Stewart was ‘pricked’ on his forehead, and his insensitivity to pain there sealed his fate. He committed suicide before he could be executed.[12]

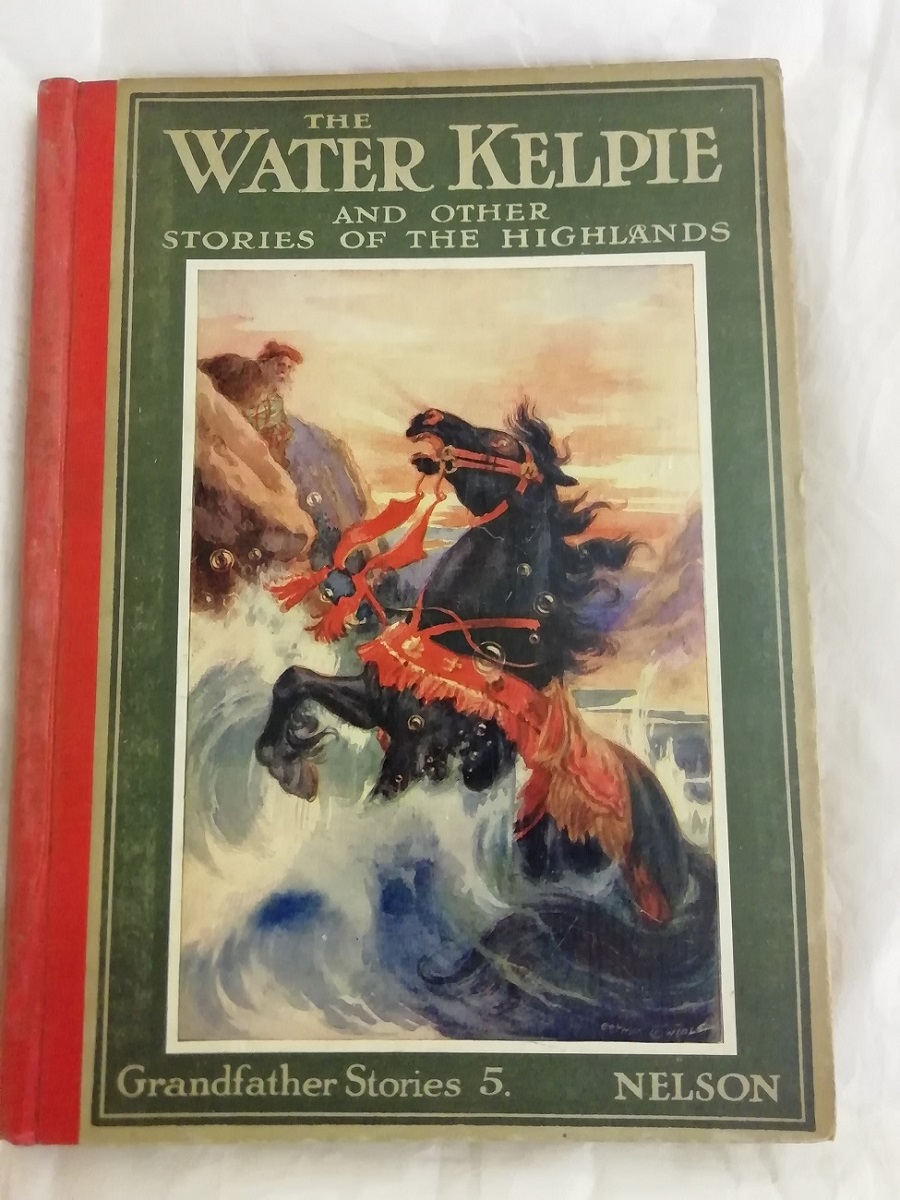

Like fairies and other mythological creatures, the kelpie was also imagined as a malevolent spirit] A particularly worrisome demonic figure in some fairy encounters was Christsonday. Described by Andro Man and others tried at Aberdeen in 1597, Christsonday appeared as a stag, riding with the fairy queen and joining their parties, but he was really the Devil in disguise. Andro claimed that Christsonday had also shown him the fires of Hell.[13] Fairies were thus associated with witchcraft, and witchcraft was an instrument of the Devil.

A particularly worrisome demonic figure in some fairy encounters was Christsonday. Described by Andro Man and others tried at Aberdeen in 1597, Christsonday appeared as a stag, riding with the fairy queen and joining their parties, but he was really the Devil in disguise. Andro claimed that Christsonday had also shown him the fires of Hell.[13] Fairies were thus associated with witchcraft, and witchcraft was an instrument of the Devil.

1700: The decline of witch trials and the rehabilitation of fairy belief

When and why did the witch trials end?

After the most intense wave of witch-hunting in 1661-2, the craze started to die down slowly. There are many possible explanations, such as the influence of English judges on the Scottish justice system, and growing scepticism about the truthfulness of accusations or at least the court’s capacity to try people fairly.[14] This sceptical attitude was part of a bigger development: the growth of scientific rationalism. Although it wasn’t atheistic at this point, science did call for a reinterpretation of the supernatural and the spiritual. Some people suggested that unlike older beliefs that saw God as having absolute power over all things in the world, perhaps God was more of an initial Creator and after that just a passive observer. These supernatural beings didn’t exist because He hadn’t made them. For some, this was preposterous – God’s supreme power being questioned?!

How did this rehabilitate fairy belief?

“In memory of the Rev. Robert Kirk, who went to his own herd, and entered into the land of the people of peace, in the year of grace sixteen hundred and ninety-two”

A few were worried by the atheistic implications of what some of these philosophers were saying. Robert Kirk was one such person. In his book The Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns and Fairies, he sought to collect evidence in a scientific manner, arguing that to doubt their existence is to doubt the existence of God Himself.[15] The idea of a spiritual realm is not that far-fetched, Kirk says, for in 1492 the discovery of the Americas “was lookt on as a fayrie tale, and the reporters hooted as inventors of ridiculous Utopias”.[16] His book is one of our best sources, and he is remembered as ‘The Fairy Minister’. Upon his death, it was rumoured that he’d been taken away by the fairies after invoking their wrath by revealing their secrets, just like Alison Peirson…

Fairies in popular culture

Scottish writers and their inspirations

Many Scottish writers have been inspired by the fairy encounters they heard about. Robert Burns, for instance, recalled an old woman in his childhood who told him tales “concerning devils, ghosts,. fairies, brownies, witches… and other trumpery” and notes the effect they had on his poetry.[17] Andrew Lang, whose fairy tales we have in the Museum of Childhood collection, also looked to the storytelling traditions of rural Scottish society for inspiration.

“If any of the very earliest myths remain in Europe, they must linger in the quiet places where such peasants tell their fairy tales, by the hearth, or in the olive shade”

George MacDonald’s descriptions of Fairyland also resemble the testimonies of the alleged witches. In The Golden Key, Fairyland is an enchanted forest, and in Phantastes the protagonist wanders around the fairy palace. Fairies come in the good sort and the wicked, and the warning from centuries ago about not offending them is echoed.[18]

Fairies in Scotland today

You can still walk the path Bessie Dunlop took to the fairy world, beginning at the Lynn Glen waterfalls. Like Robert Burns in his poem ‘Halloween’, you might find the fairies dancing on Cassilis Downans, the very hills that Isobel Gowdie described in 1662. [19]

“Upon that night, when fairies light

On Cassilis Downans dance”

Doon Hill is the site where Robert Kirk mysteriously died – some believe his spirit still wanders there, others that it is trapped in the large pine tree at the top of the hill. Countless more hills bear Gaelic names referring to their inhabitants: Cailleach Bheur, Neimheadh, and Sithe.[20]

The history of fairy belief in Scotland has left traces in our environment and our imaginations. At the Museum of Childhood, we have a number of fairy tale collections where you are sure to find yourself recalling Bessie Dunlop, Robert Kirk and other Scots whose words and experiences have ensured the survival of these remarkable stories. At the Writers’ Museum, you can also meet the great Scottish writers whose pens inked some of these tales. They, like you, were looking backwards into the past. Whether you’re traversing the enchanted Scottish landscape, or staying comfortably indoors with a collection of fairy tales, over 500 years of history is before you.

Ruksar Hussain is a History student at Oxford University, and has an interest in postcolonial theory and social and cultural history. Ruksar was on a Crankstart Internship with Museums &Galleries Edinburgh in Spring 2022.

Footnotes

[1] Child, F.J. & Kittredge, G.L., 1882. The English and Scottish popular ballads, Boston : London: Houghton, Mifflin and Co.; Henry Stevens, Son and Stiles, p.325.

[2] Henderson, L. & Cowan, E.J., 2001. Scottish fairy belief : a history, East Linton: Tuckwell Press, p.5.

[3] Ibid., p.13.

[4] Weston, J., 2016. Demonizing the Fairies: Scottish Ministers and Preternatural Beliefs During the Scottish Witch Hunts. Master of Arts. Crandall University, p.93.

[5] Henderson and Cowan, p.15.

[6] Ibid., pp.45-47.

[7] Ibid., pp.117-118.

[8] Sharpe, J., 2002. Anglo-Scottish Comparisons. In: J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish witch-hunt in context. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp.189-190.

[9] Henderson and Cowan, pp.122-123.

[10] MacCulloch, Canon J. A, 1921. The Mingling of Fairy and Witch Beliefs in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Scotland. Folklore (London), 32(4), p.234.

[11] Ibid., p.234.

[12] Henderson and Cowan, pp.130-131.

[13] MacCulloch, pp.235-236.

[14] Levack, Brian P, 1980. The Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1661–1662. The Journal of British studies, 20(1), pp.92-93.

[15] Henderson and Cowan, pp.171-2.

[16] Henderson, Lizanne Frances, 1997. The guid neighbours: Fairy belief in early modern Scotland, 1500–1800, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, p.162.

[17] MacCulloch, p.231.

[18] Pazdziora, J., 2013. How the Fairies were not Invited to Court. In: C. MacLachlan, J. Pazdziora and G. Stelle, ed., Rethinking George MacDonald : contexts and contemporaries. Glasgow: Scottish Literature International., pp.257-9.

[19] Henderson and Cowan, p.41. ; Burns, Robert, 1919. Robert Burns, New York: Co-operative Publication Society, p.99.

[20] LaViolette, P. and McIntosh, A., 1997. Fairy hills: merging heritage and conservation. ECOS - a review of conservation, 18(3), pp.2-8.