Auld Reekie Retold is a major three year project which connects objects, stories and people using Museums & Galleries Edinburgh’s collection of over 200,000 objects. Funded by the City of Edinburgh Council and Museums Galleries Scotland, the project brings together temporary Collections Assistants and permanent staff from across our venues. The Auld Reekie Retold team are recording and researching our objects, then showcasing their stories through online engagement with the public. We hope to spark conversations about our amazing collections and their hidden histories, gathering new insights for future exhibitions and events.

In this blog, Helen Edwards, Decorative Art Curator has been investigating the stories behind some of the pieces in our silver collection.

Because silver is hallmarked, you can find out when and where it was made as well as who made it. The Incorporation of Goldsmiths of Edinburgh’s hallmarking archive is a good way of finding out more about individual pieces. Sometimes you discover things which makes you look at an object in a new light. One example is this pair of sugar casters and their link to a scheme that altered the course of Scotland’s History.

These elegant pieces of silverware, along with the sugar they contained, would show off your wealth and status. Yet behind this sweetness was the misery of African slaves who laboured to produce this sugar on plantations in the West Indies and America. Their life expectancy was only half that of other forms of field slavery - a huge price to pay for people in Scotland to add sugar to their food and drinks.

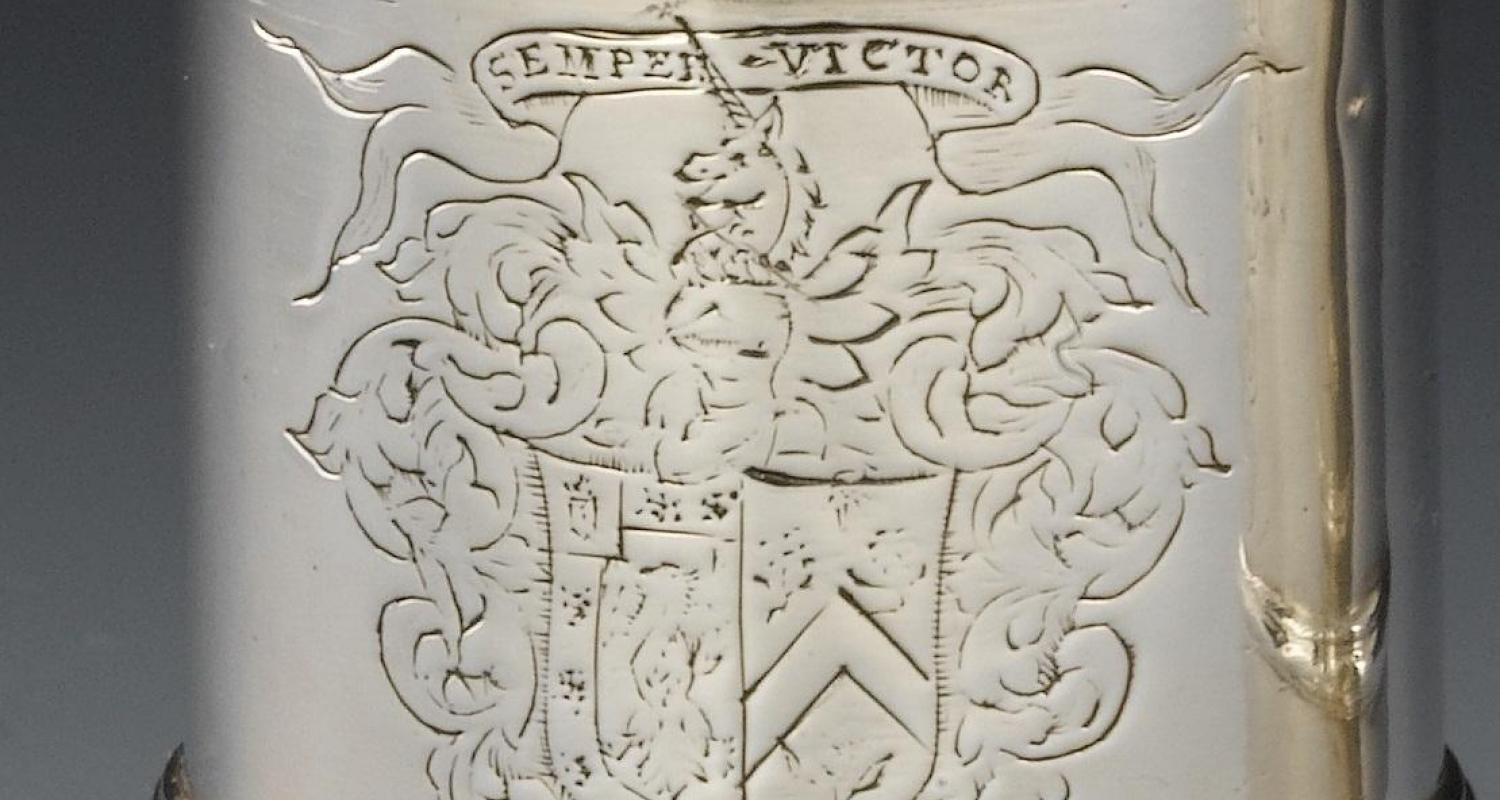

They are engraved with the arms of Sir John Ramsay of Whitehill in Midlothian and his first wife Anna Carstairs, who died in 1689. They were made about 18 months before his re-marriage to Rosina Purves in December 1695. The motto ‘Sempre victor’ translates as 'always victorious'.

But what makes these pieces really interesting is their link to Scotland’s failed attempt to become a leader in 17th century world trade.

They were made by Edinburgh Goldsmith Andrew Law 1694. Law’s father and uncle were both goldsmiths. He became his Uncle’s apprentice on 11 September 1683 and after working as a Journeyman became a Freeman of the Incorporation of Edinburgh Goldsmiths on 27th March 1694. By 1698 he had a shop in Parliament Close, a popular area for many of Edinburgh’s leading goldsmiths as it was close to Goldsmiths Hall, Parliament House and the Law Courts, as well as the coffee houses. Here your shop would be in prime position for attracting wealthy customers.

Andrew Law’s makers mark was AL and a crown within a shield. The three-towered castle is the Edinburgh town mark. The date letter ‘n’ is for 1693-4 and covers two years because the date letter did not change on January 1st. As Andrew Law became a freeman in March 1694, then 1694 is the most likely date for this piece. The letter B is for John Borthwick the Assay Master whose mark ensured the silver was the required quality.

In 1695 Andrew law was accused of breaking the incorporation rules by employing goldsmiths from Canongate. Yet this this transgression did not prevent him from being made Deacon in 1696 at the unusually early age of 23. He served as Deacon until 1698 but his success didn’t last as he became embroiled in the Darien Scheme.

This was Scotland’s attempt in the late 1690s to establish a colony on the Gulf of Darien in what is now Panama. The plan was to connect trade in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans and was the brainchild of William Paterson, a Scot who had heard of the wonders of Darien from a sailor, while helping to set up the bank of England south of the border. England was initially a willing partner but withdrew support following protests from the East India Company. Support from the Netherlands and Germany also faded leaving Scotland to finance the venture alone. Thousands of Scots invested in what appeared to be a lucrative venture. The first ships set sail from Leith on the 12th of July 1698, arriving on the 12th of October, but like many tales of distant places reality was very different. Many settlers died from illness and hunger but as news travelled slowly more ships were dispatched before the disastrous reality of the situation was understood. Of the 2500 settlers who set sail only a few hundred survived. Back in Scotland many people lost their fortunes and the far-reaching financial consequences may have been one of the reasons for the Act of Union in 1707.

And what of Andrew Law? Well he was imprisoned for debt in 1698, long before news of Darian’s failure reached Scotland. Records in the Incorporation’s archives state he was imprisoned for a debt of 300 pounds, and also state it was as result of the Darien Scheme, so perhaps in the rush to invest in what seemed a lucrative venture he spent more than he could afford. Thanks to money from the Incorporation he was able to get out of prison and presumably return to his livelihood. We don’t know anything of his later career, but he died aged 30 in September 1703.

You can see more items from our silver collection online at www.capitalcollections.org.uk